Reading How Git works

How Git saves a project history

Git saves the history of your project as a series of snapshots. Small Git objects called commits point to these snapshots.

Each commit is identified by a unique 40-character checksum SHA-1 often simply referred to as a "hash".

Example of a Git SHA-1: 1f5eaef51fcef3f3410dfe8696ff924b10d25b31

Commits contain information about the author of the snapshot, the date and time when it was made, as well as the SHA-1 of its parent commit(s) so that Git can keep track of where it fits in the project history relative to other commits.

The three trees of Git

Git has a three-tree architecture:

- The working directory or working tree:

An uncompressed version of your files that you can access and edit. You can think of it as a sandbox. This is what is in your project outside the

.gitfolder and what you usually think of as "your files".

- The index or staging area:

The suggested future snapshot that would be recorded if you ran

git commit.

- HEAD:

The snapshot of the project at the commit

HEADis pointing to.

Making changes to the working tree

When you make changes to your project, you make changes in the working directory or working tree.

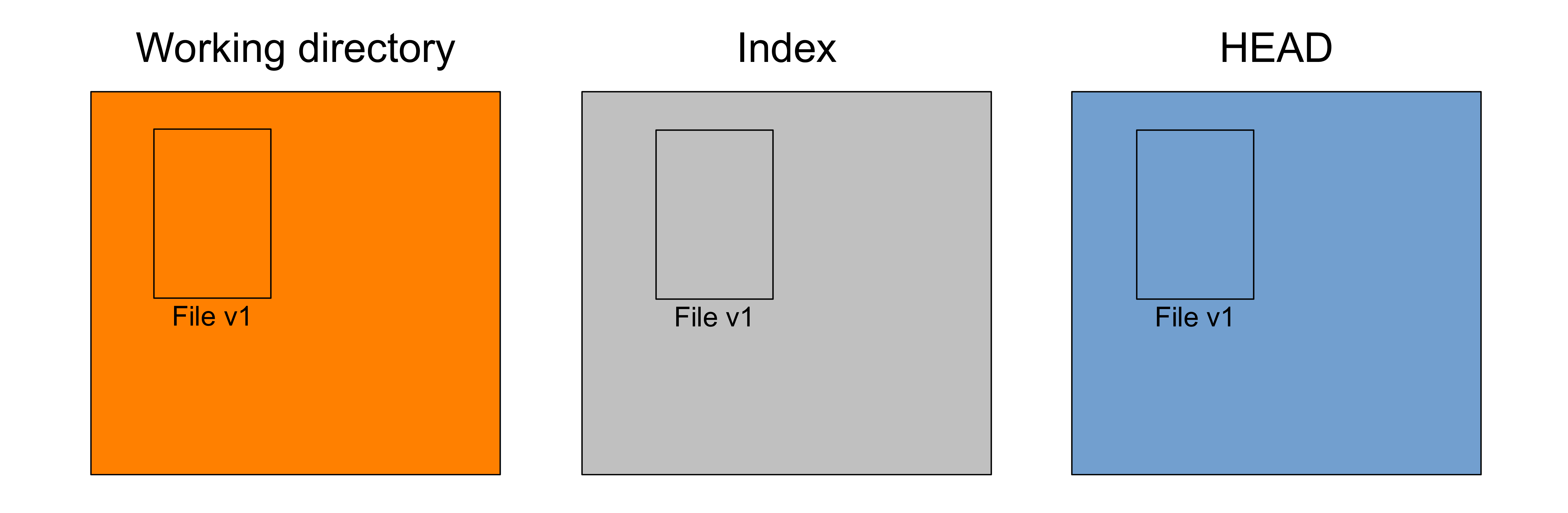

Here is an illustration of the three trees for a project with a single file called File after the first commit (let's say that it is at version v1):

The three trees are at the same stage. Your working tree is "clean".

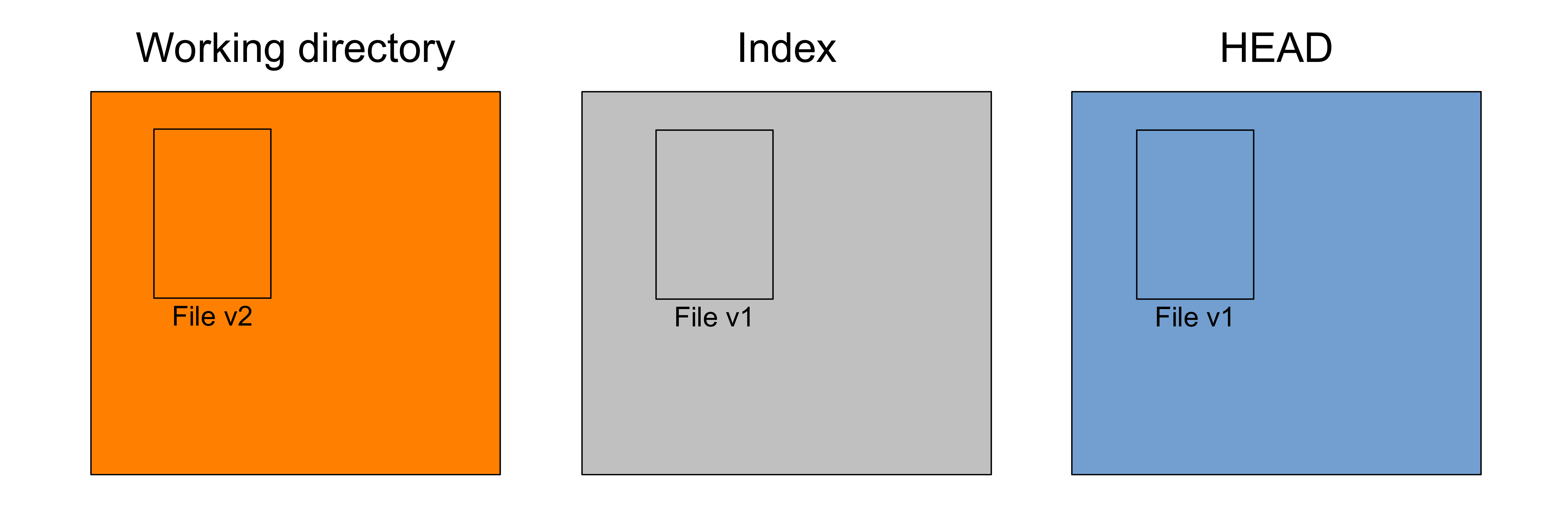

Now, you make a change to File —for instance you add a few lines of code—(let's say that it is now at version v2):

When you edit files in your project, you are making changes in the working tree. The other trees remain at version v1.

To display the status of the Git trees, you can run:

git statusThis is what you get:

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: File

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")Staging changes

You stage that file (meaning that you will include the changes of that file in the next commit) with:

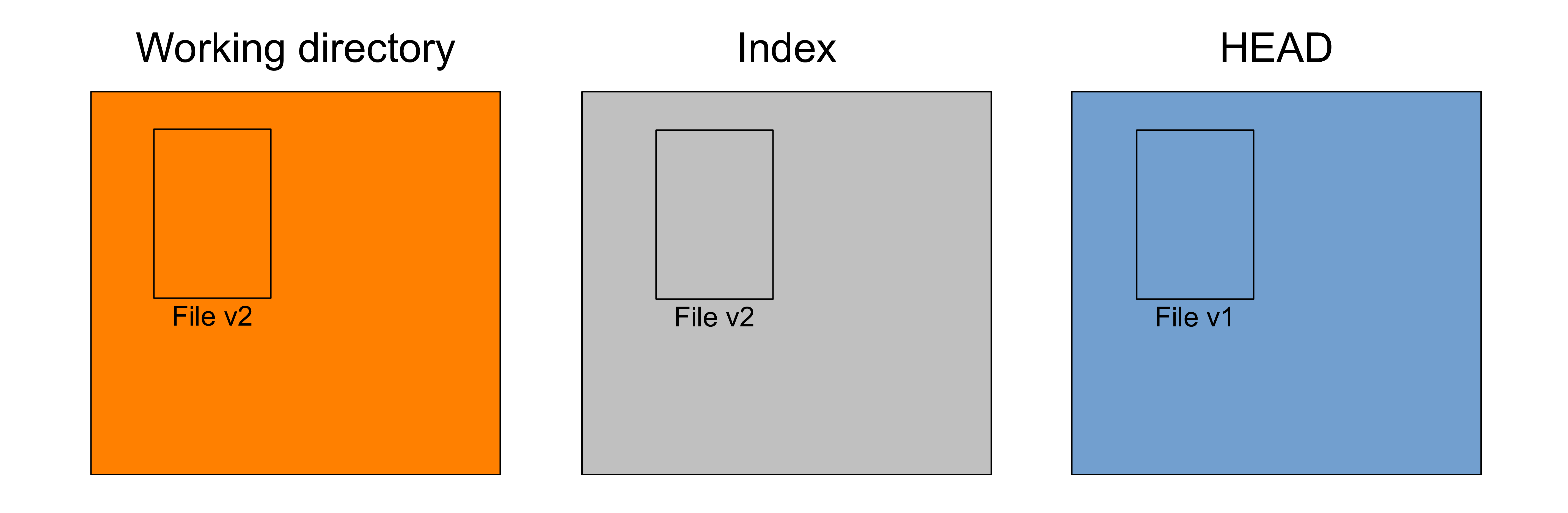

git add FileAfter which, your Git trees look like this:

Now, the index also has File at version v2.

git status now returns:

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

modified: FileCommitting changes

Finally, you make a commit, recording the staged changes to history with:

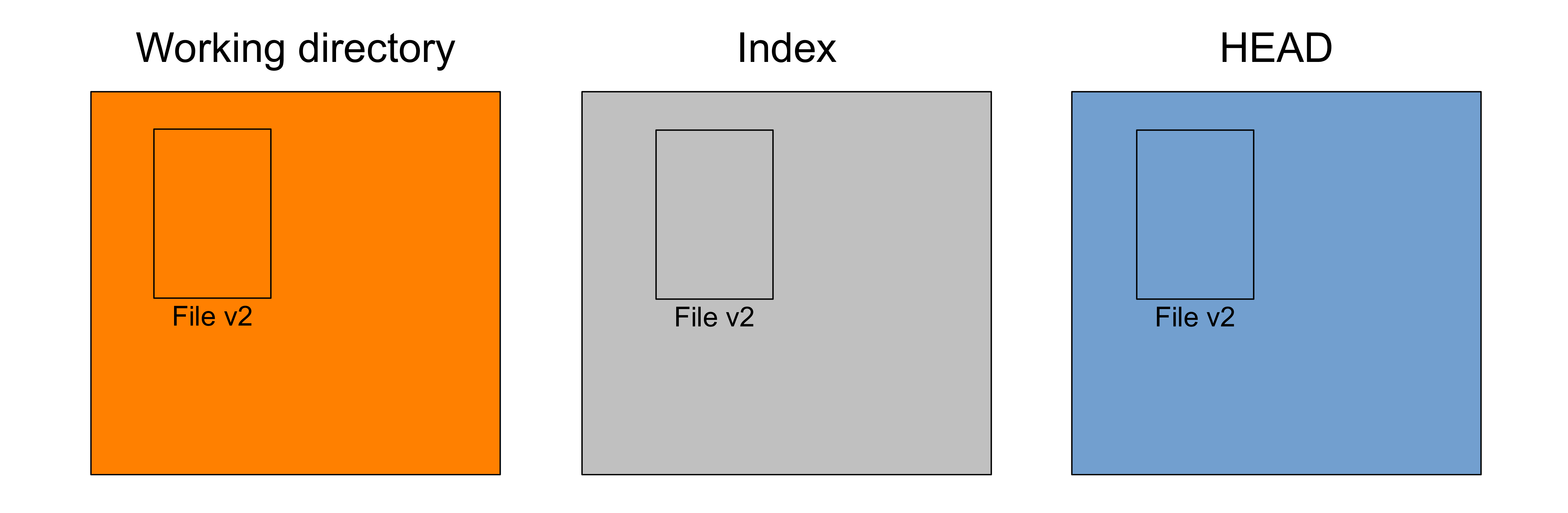

git commit -m "Added File"And your trees look like:

Now git status returns:

On branch master

nothing to commit, working tree cleanThis means that there are no uncommitted changes in your working tree or the staging area: all your changes have been written to history and your working tree is clean again.

Why a two-stage process?

The reason for this two-stage process is that it allows you to pick and choose the changes that you want to include in a commit. Instead of having a messy bag of all your current changes whenever you write a commit, you can select changes that constitute a coherent unit and commit them together, leaving unrelated changes to be committed later. This allows for a clearer history that will be easier to revisit in the future.

Comparing trees with one another

git diff can show the differences between any two of your three trees.

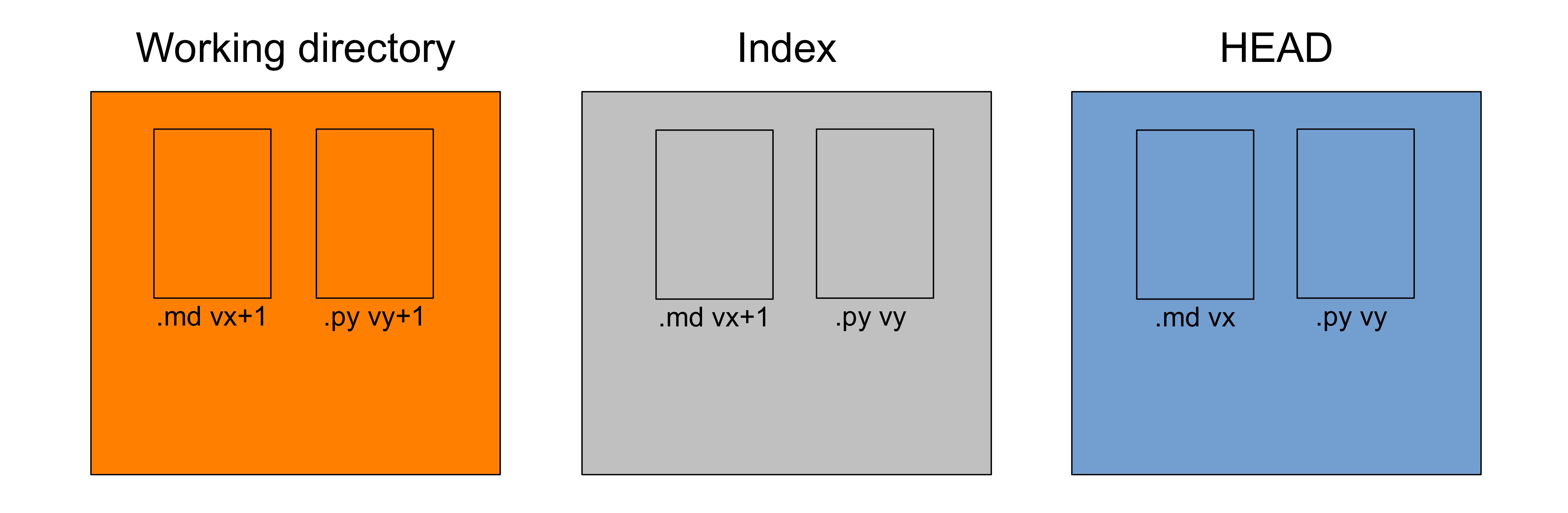

Let's imagine that our three trees look like this:

We have a markdown manuscript (symbolized by .md in the figure) and a Python script (symbolized by .py).

In our last commit, we saved a snapshot while they were at version vx and vy respectively. This is what HEAD shows (HEAD points to our last commit).

Then we made changes to the manuscript (so it is now at version vx+1 in the working directory) and we staged those changes (so .md is also at version vx+1 in the index).

Finally, we made changes to our script (which is thus now at version vy+1 in the working directory), but we did not stage those changes.

At this point, our three trees are all different from each other.

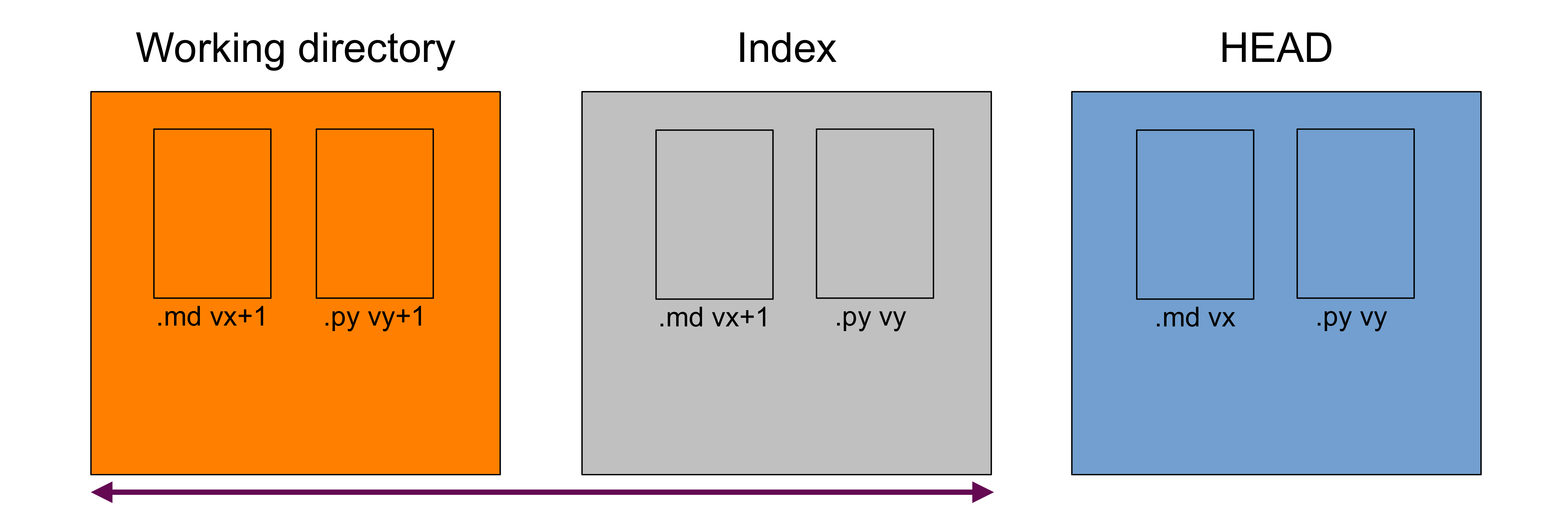

Difference between the working directory and the index

That's all your unstaged changes on tracked files (new files will not be shown)*.

You can get those differences with:

git diff

This will show you all the differences in the Python script between versions vy and vy+1.

*Git can detect new files you have never staged: it lists them in the output of git status. Until you put them under version control by staging them for the first time however, Git has no information about their content: at this point, they are untracked and they are not part of the working tree yet. So their content never appears in the output of git diff.

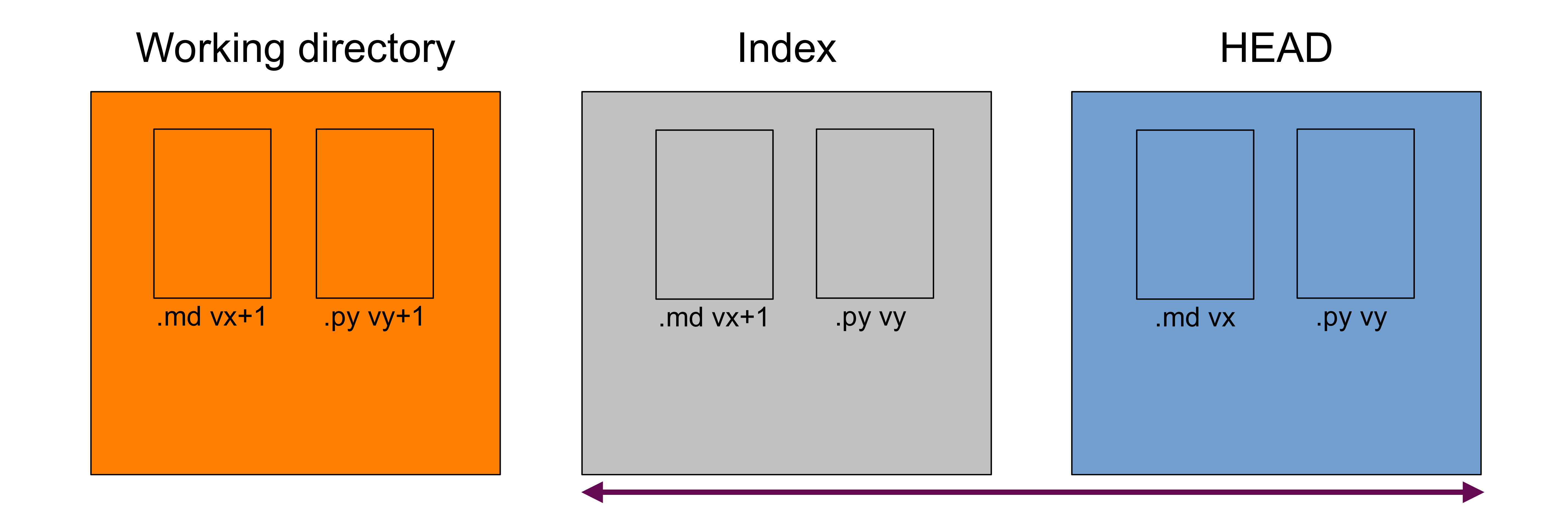

Difference between the index and your last commit

That's your staged changes ready to be committed. That is, that's what would be committed by git commit -m "Some message".

You get those differences with:

git diff --cached

This will show you all the differences in the markdown manuscript between versions vx and vx+1.

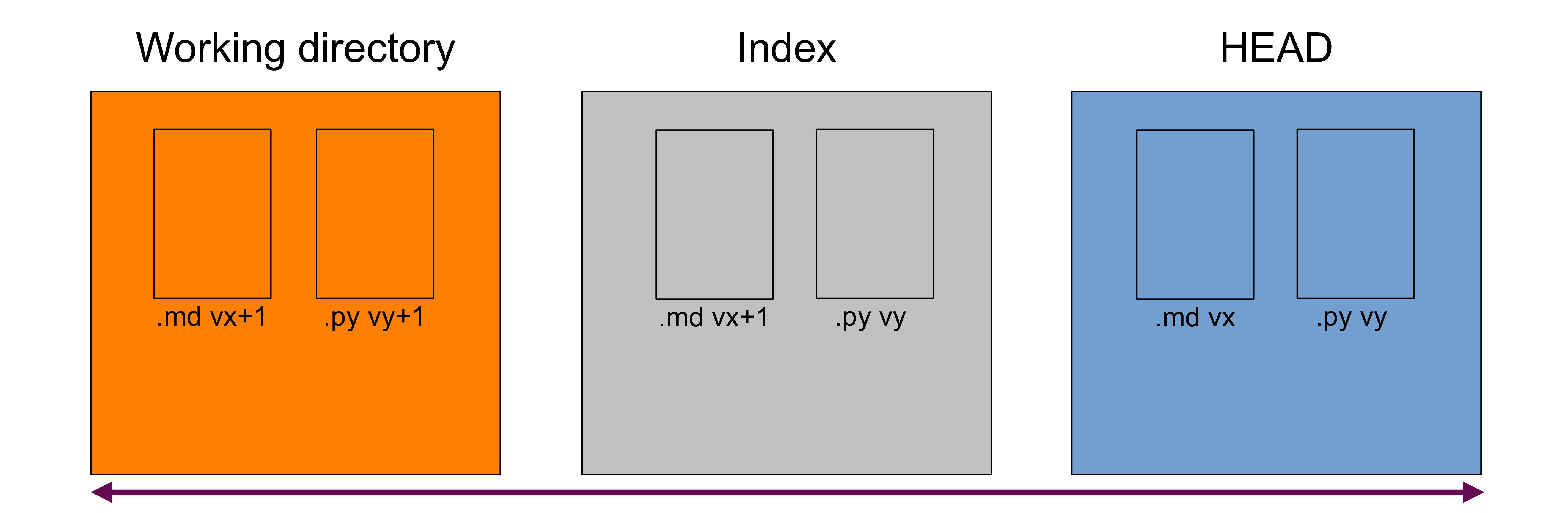

Difference between the working directory and your last commit

This is the combination of the previous two, that is, all your staged and unstaged changes (again, only on tracked files).

You can display those differences with:

git diff HEAD

This will show you the differences in the Python script between versions vy and vy+1 and in the markdown manuscript between versions vx and vx+1.

Commit history

When you write a commit, the proposed snapshot that was in your staging area gets archived inside the .git repository in a compressed form and is now part of your project history.

HEAD is a pointer indicating where you currently are in the commit history.

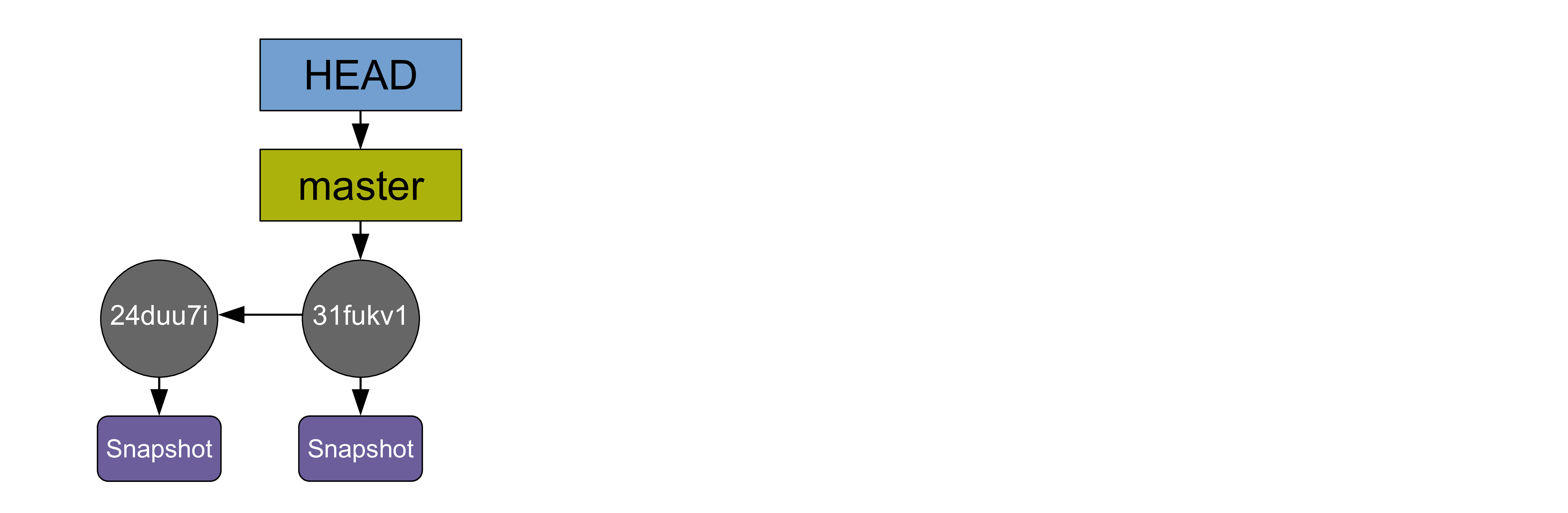

After you have made your first commit, this is what your history looks like:

HEAD points to master which is the name Git gives to the default branch when you initialize a Git repository. We will talk about branches later. 24duu71 is the short SHA-1 of your first commit (the 7 first characters of the SHA-1 for that commit).

If you make new changes in your project, stage all or some of them, and create a new commit, as we saw earlier, your history will then look like:

Here is what happened when you created that new commit:

- a new snapshot got archived,

- a new commit (with a new unique SHA-1) pointing to that snapshot got created,

- the

masterbranch andHEADmoved to point to the new commit.

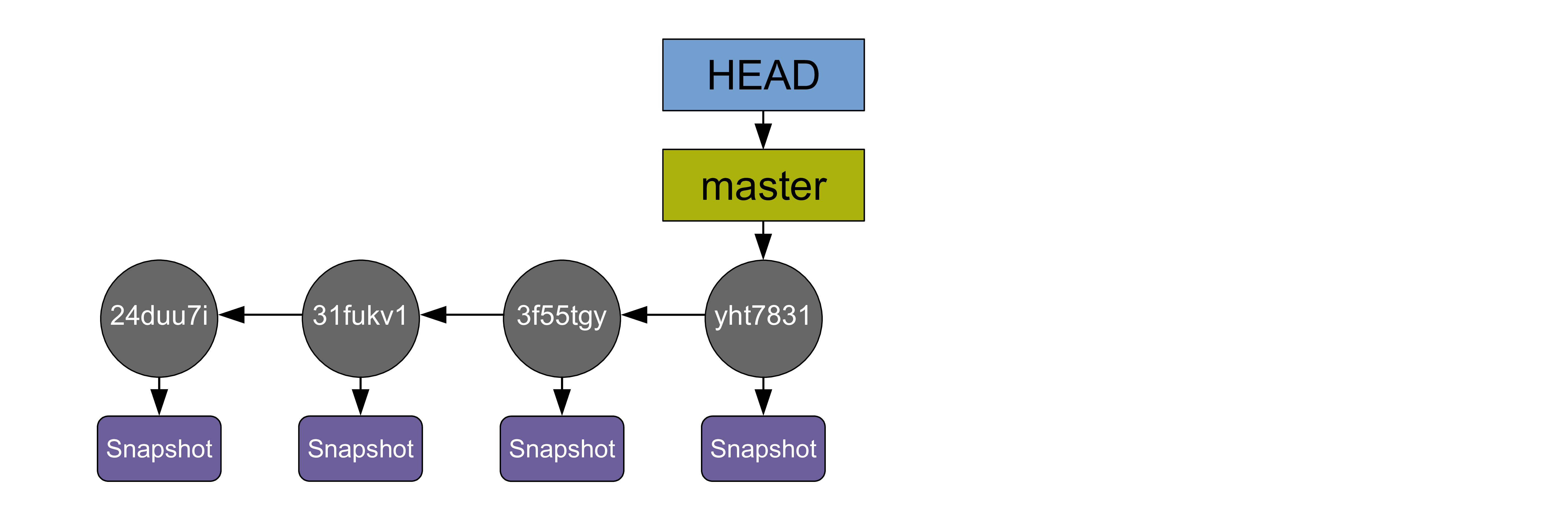

After another two commits, your history looks like this:

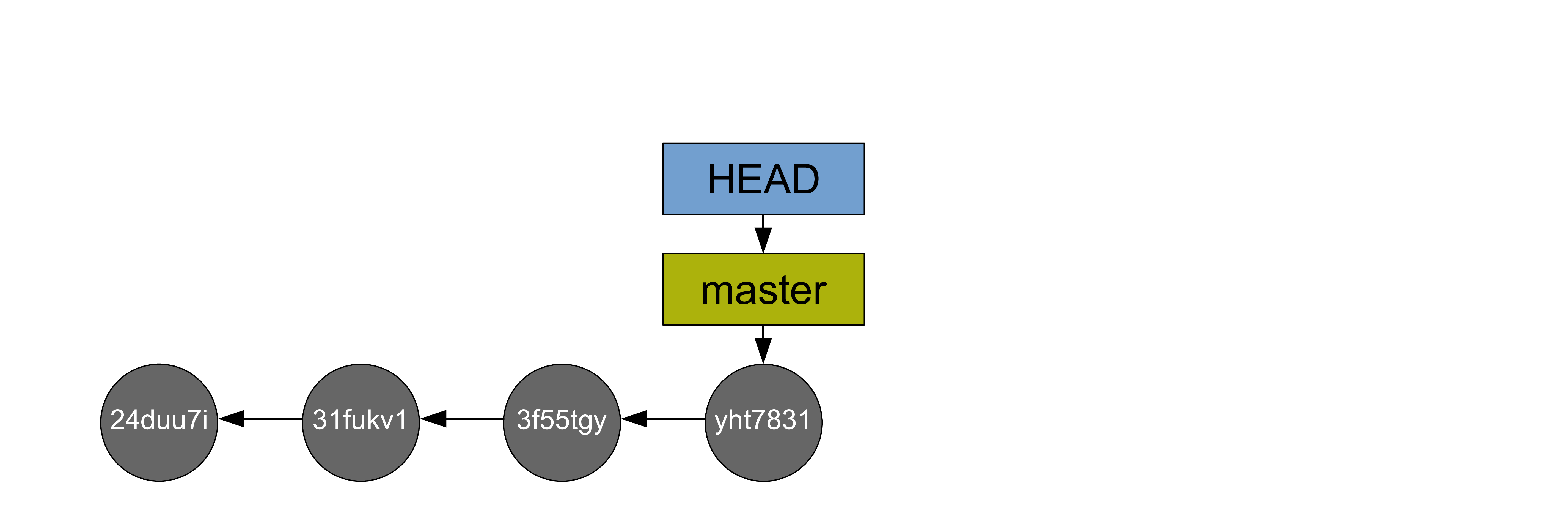

From now on, since every commit points to a snapshot of your project, I will represent simplified graphs in this way:

Displaying the commit history

git log lists past commits in a pager (less by default) and allows you to get an overview of a project history.

It comes with many flags which allow countless variations. Here are few useful ones:

Log as a list

By default git log gives a lot of information for each commit. While this is sometimes useful, if you want to get a clear picture of your overall project history, it may be better to reduce each commit log to a one-liner:

git log --onelineYou can customize the commit log to your liking by playing with colors, time format, etc.

Try for instance:

git log \

--graph \

--date-order \

--date=short \

--pretty=format:'%C(cyan)%h %C(blue)%ar %C(auto)%d'`

`'%C(yellow)%s%+b %C(magenta)%ae'

To see all the available flags, run man git-log.

Log as a graph

The --graph flag allows to view this history in the form of a graph.

git log --graphThis may not seem very useful with our simple history because it is linear with a single branch, but in complex histories with several branches, this is really helpful.