- Why version control?

- Git

- Configuration

- Documentation

- Troubleshooting & getting help

- Recording history

Break

- Working with branches

Lunch Break

- Exploring the past

- Undoing

Break

- Remotes

- Collaborating

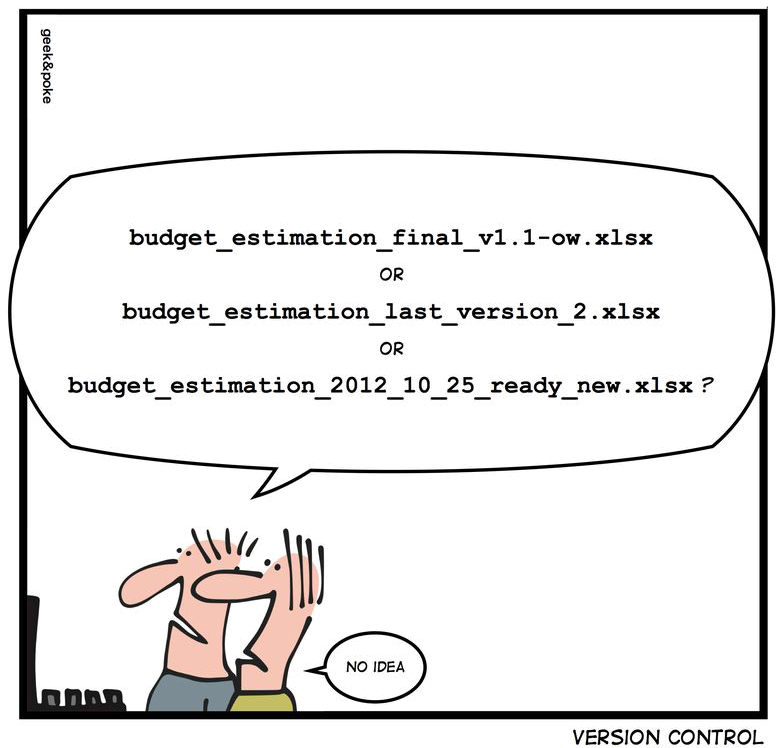

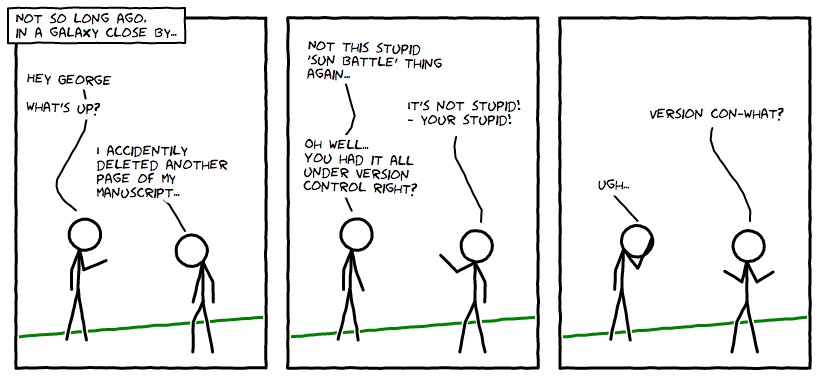

Why version control?¶

Why version control?

A sophisticated form of backup¶

There are two kinds of people: those who do their backups well and those who will.

Git

Git is an open source distributed version control system (DVCS) created in 2005 by Linus Torvalds for the versioning of the Linux kernel during its development.

In distributed version control systems, the full history of projects lives on everybody's machine—as opposed to being only stored on a central server as was the case with centralized version control systems CVCS. This allows offline work, huge speedups, easy branching, and multiple backups. DVCS have taken over CVCS.

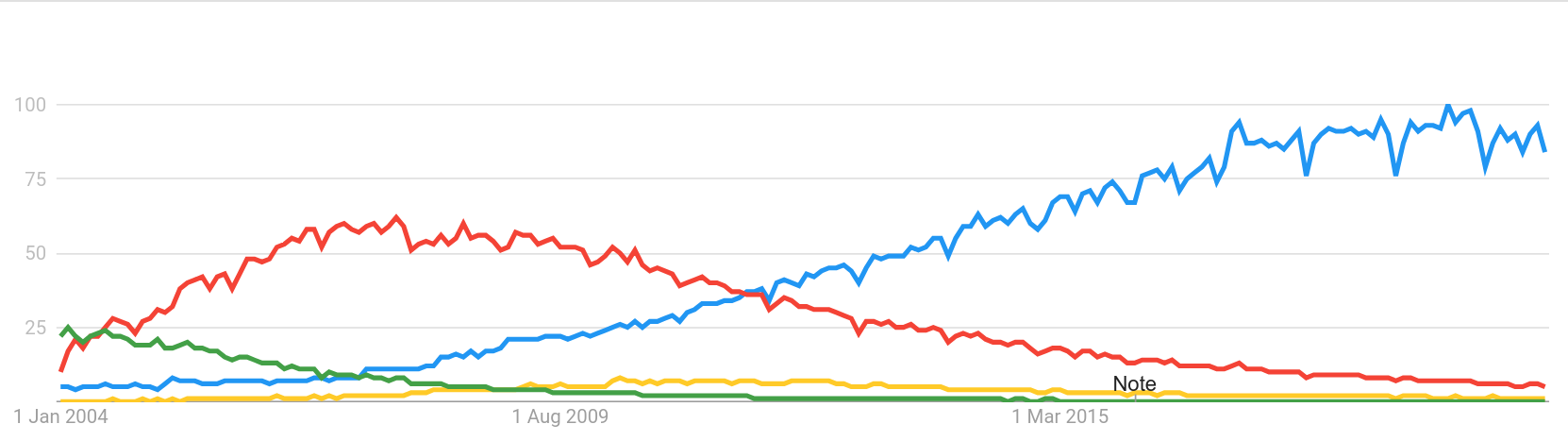

Git is extremely powerful and has strong branching capabilities. Since the early 2010s, it has become the most popular DVCS, increasingly rendering other systems quite marginal.

Git

All commands start with git.

A typical command is of the form:

git <command> [flags] [arguments]

Example:

We already saw the following:

git config --global "Your Name"

Configuration¶

Configuration

Global configuration¶

From anywhere, with the --global flag.

There are a number of configurations necessary to set before starting to use Git.

Configuration

Global configuration¶

Set the name and email address that will appear as signature of your commits:

git config --global user.name "Your Name"

git config --global user.email "your@email"

Configuration

Global configuration¶

Set the text editor you want to use with Git:

git config --global core.editor "editor" # e.g. "nano", "vim", "emacs"

Configuration

Global configuration¶

Format line endings properly:

git config --global core.autocrlf input # if you are on macOS or Linux

git config --global core.autocrlf true # if you are on Windows

Example:

git config --list

Configuration

Project-specific configuration¶

You can set configurations specific to a single repository (e.g. maybe you want to use a different email address for a certain project).

In that case, make sure that you are in the repository you want to customize and run the command without the --global flag.

Example:

cd /path/to/project

git config user.email "your_other@email"

Documentation¶

Documentation

Man pages¶

You can access the man page for a git command with either of:

git <command> --help

git help <command>

man git-<command>

Note:

Throughout this workshop, I will be using < and > to indicate that an expression needs to be replaced by the appropriate expression (without those signs).

man git-commit

git commit -h

Troubleshooting Getting help¶

Troubleshooting & getting help

"Listen" to Git!¶

Git is extremely verbose: by default, it will return lots of information. Read it!

These messages may feel overwhelming at first, but:

- they will make more and more sense as you gain expertise

- they often give you clues as to what the problem is

- even if you don't understand them, you can use them as Google search terms

Troubleshooting & getting help

(Re-read) the doc¶

As I have no memory, I need to check the man pages all the time. That's ok! It is quick and easy.

For more detailed information and examples, I really like the Official Git manual.

Troubleshooting & getting help

Don't panic

Be analytical

Be analytical

It is easy to panic and feel lost if something doesn't work as expected.

Take a breath and start with the basis:

- make sure you are in the repo (

pwd) and the files are where you think they are (ls -a) - inspect the repository (

git status,git diff,git log). Make sure not to overlook what Git is "telling" you there

Commit and push often to be safe.

Recording history¶

Recording history

Create the project root¶

- Navigate to the location where you want to create your project.

- Create a new directory with the name of your project.

**Never use spaces in names and paths.**

pwd

cd ~/parvus/ptmp

pwd

ls

mkdir ocean_temp

ls

Recording history

Put the project under version control¶

**Make sure to enter your new directory before initializing version control.**

A classic mistake leading to lots of confusion is to run git init outside the root of the project.

pwd

cd ocean_temp

pwd

ls -a

git init

ls -a

ls -a .git

git status

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

Recording history

Create a sensible project structure¶

mkdir src result ms data

ls -a

tree

git status

Recording history

Add first file¶

Note: Git—which is such a powerful tool—works on any text files.

If you write your manuscript as a text file (e.g. .org, .md, .Rmd, .txt, .ipynb) rather than a MS Word or LibreOffice Writer file, you can put it under version control.

This has countless advantages, from easy versioning to easy collaboration.

echo "import numpy as np

years = list(range(2001, 2020))" > src/enso_model.py

tree

git status

**Under the hood**

git add .

git status

**Under the hood**

git commit -m "Initial commit"

git status

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

Recording history

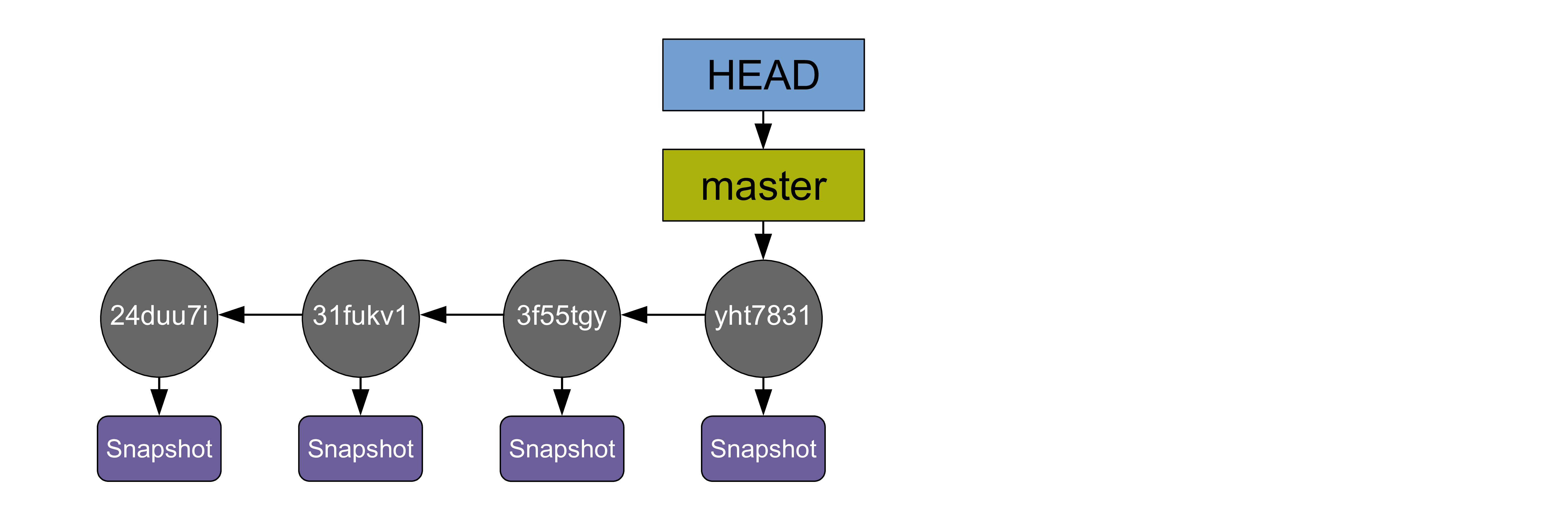

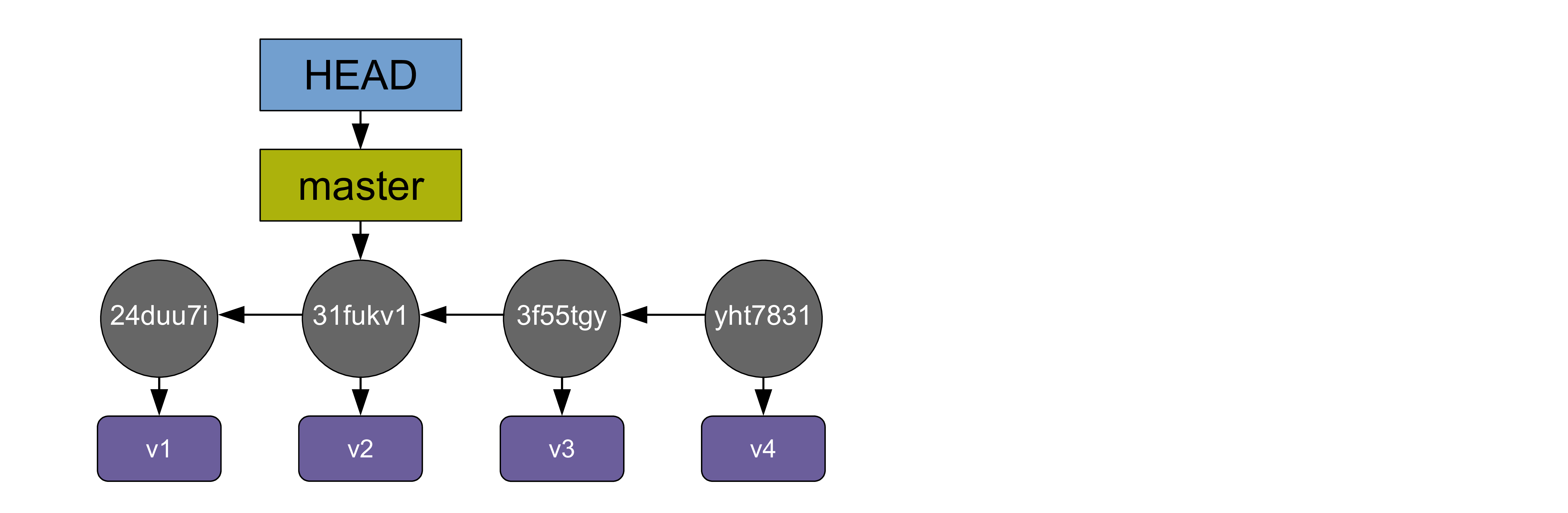

SHA-1 checksum¶

Each commit is identified by a unique 40-character SHA-1 checksum. People usually refer to it as a “hash”.

The short form of a hash only contains the first 7 characters, which is generally sufficient to identify a commit.

After you committed, Git gave you the short form of the hash of your first commit.

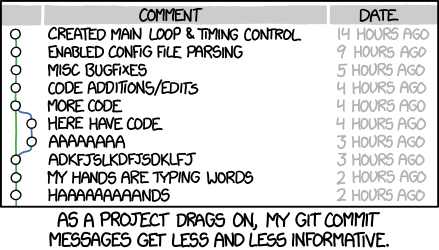

Use the present tense

The first line is a summary of the commit and is less than 50 characters long

Leave a blank line below

Then add the body of your commit message with more details

Use the present tense

The first line is a summary of the commit and is less than 50 characters long

Leave a blank line below

Then add the body of your commit message with more details

Recording history

Example of a good commit message:

git commit -m "Reduce boundary conditions by a factor of 0.3

Update boundaries

Rerun model and update table

Rephrase method section in ms"

emacsclient -c src/enso_model.py # Replace 'emacsclient -c' by your text editor of choice

git status

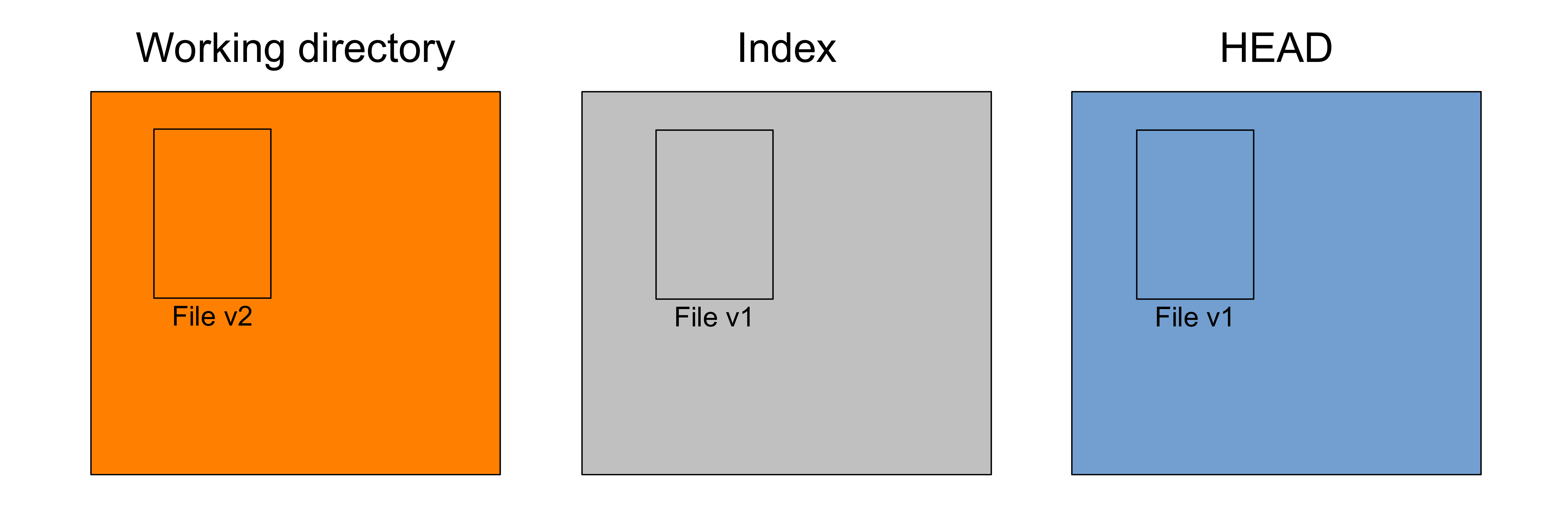

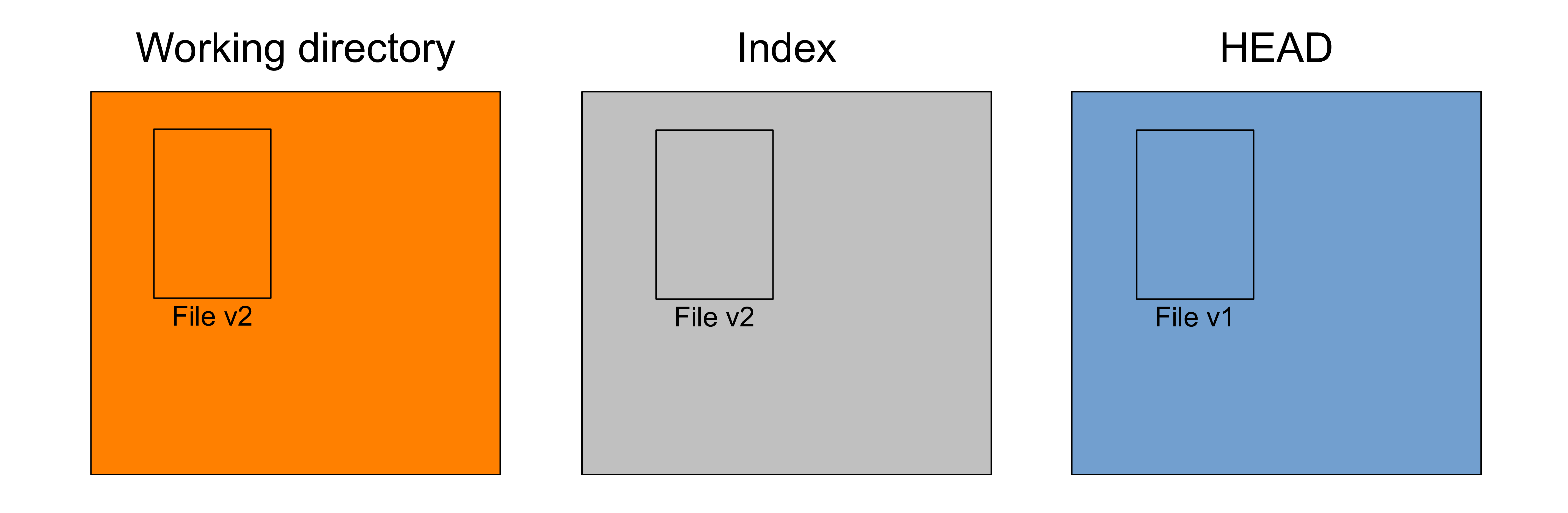

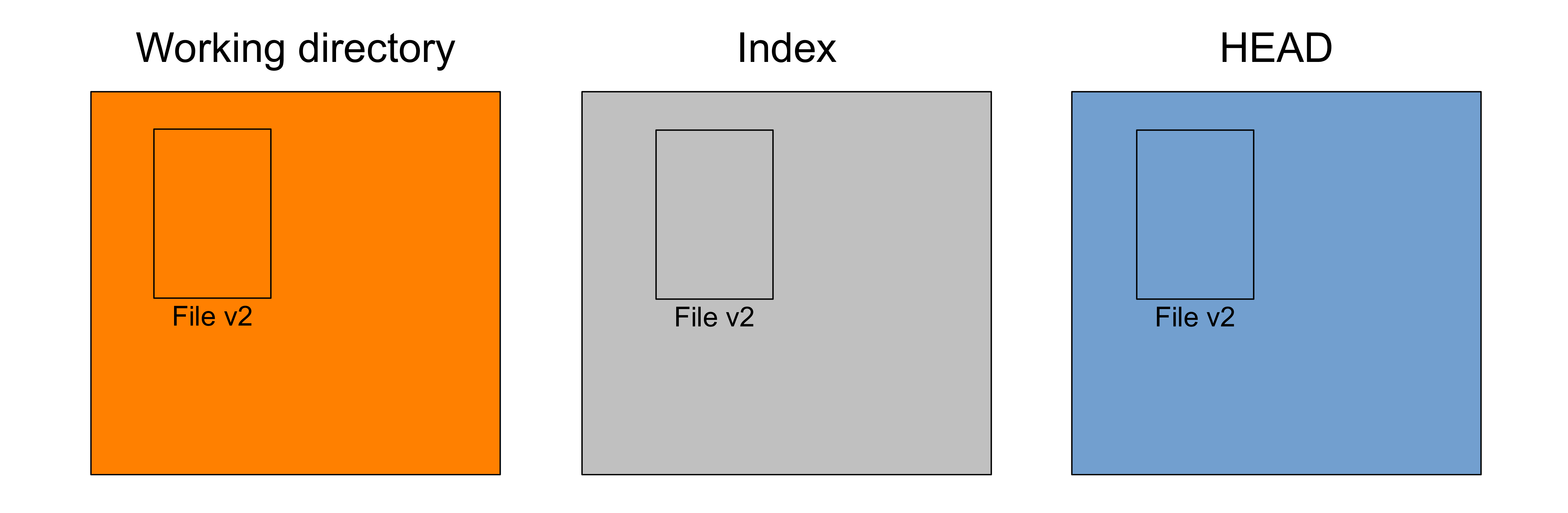

**Under the hood**

git add .

git status

**Under the hood**

git commit -m "Modify enso script"

git status

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

Recording history

Excluding from version control¶

There are files you really should put under version control, but there are files you shouldn't.

Put under vc¶

- Scripts

- Manuscripts and notes

- Makefile and the like

Do not put under vc¶

- Non-text files (e.g. images, office documents)

- Outputs that can be recreated by running code

Recording history

Excluding from version control¶

You want to have a clean working directory, so you need to tell Git to ignore those files.

You do this by adding them to a file that you create in the root of the project called .gitignore.

touch result/graph.png

tree

git status

echo /result/ > .gitignore

cat .gitignore

git status

Recording history

.gitignore rules¶

Each line in a .gitignore file specifies a pattern.

Blank lines are ignored and can serve as separators for readability.

Lines starting with # are comments.

To add patterns starting with a special character (e.g. #, !), that character needs escaping with \.

Trailing spaces are ignored unless they are escaped with \.

! negates patterns (matching files excluded by previous patterns become included again). However it is not possible to re-include a file if one of its parent directories is excluded (Git doesn’t list excluded directories for performance reasons). One way to go around that is to force the inclusion of a file which is in an ignored directory with the option -f.

Example: git add -f <file>

Patterns ending with / match directories. Otherwise patterns match both files and directories.

/ at the beginning or within a search pattern indicates that the pattern is relative to the directory level of the .gitignore file. Otherwise the pattern matches anywhere below the .gitignore level.

Examples:

- foo/bar/ matches the directory foo/bar, but not the directory a/foo/bar

- bar/ matches both the directories foo/bar and a/foo/bar

* matches anything except /.

? matches any one character except /.

The range notation (e.g. [a-zA-Z]) can be used to match one of the characters in a range.

A leading **/ matches all directories.

Example: **/foo matches file or directory foo anywhere. This is the same as foo

A trailing /** matches everything inside what it precedes.

Example: abc/** matches all files (recursively) inside directory abc

/**/ matches zero or more directories.

Example: a/**/b matches a/b, a/x/b, and a/x/y/b

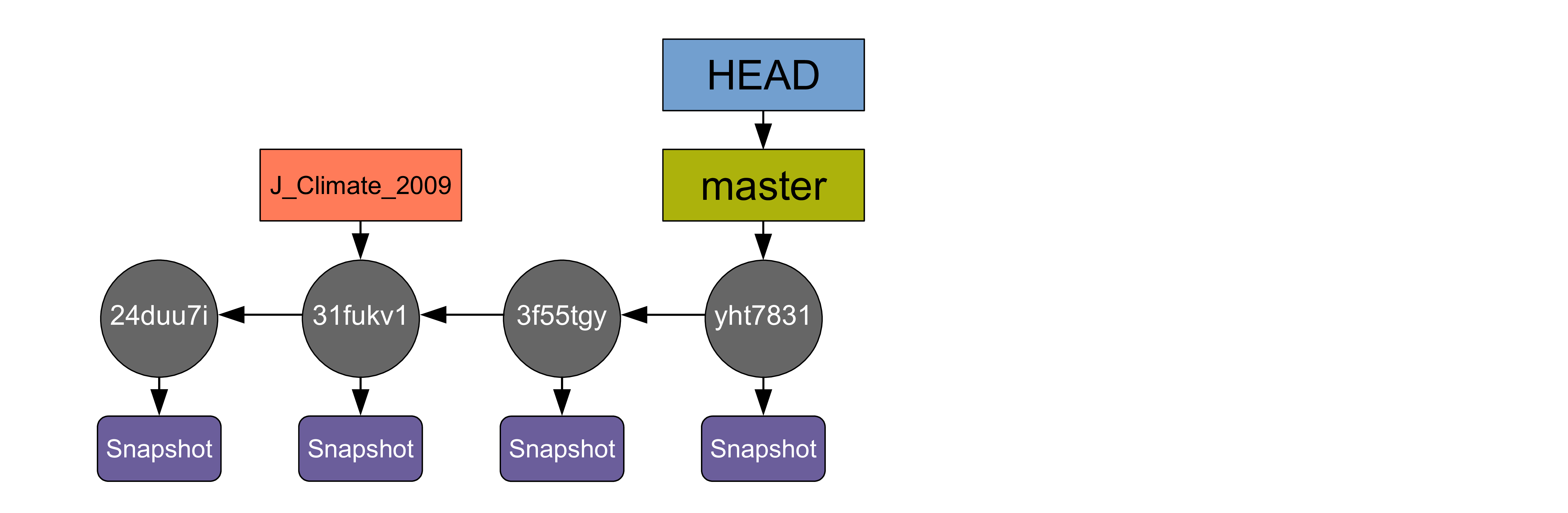

git tag

git tag -a J_Climate_2009 -m "State of project at the publication of paper"

git show J_Climate_2009

git tag

git tag J_Climate_2009_light

git show J_Climate_2009_light

git tag

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

git tag -d J_Climate_2009_light

git tag

Recording history

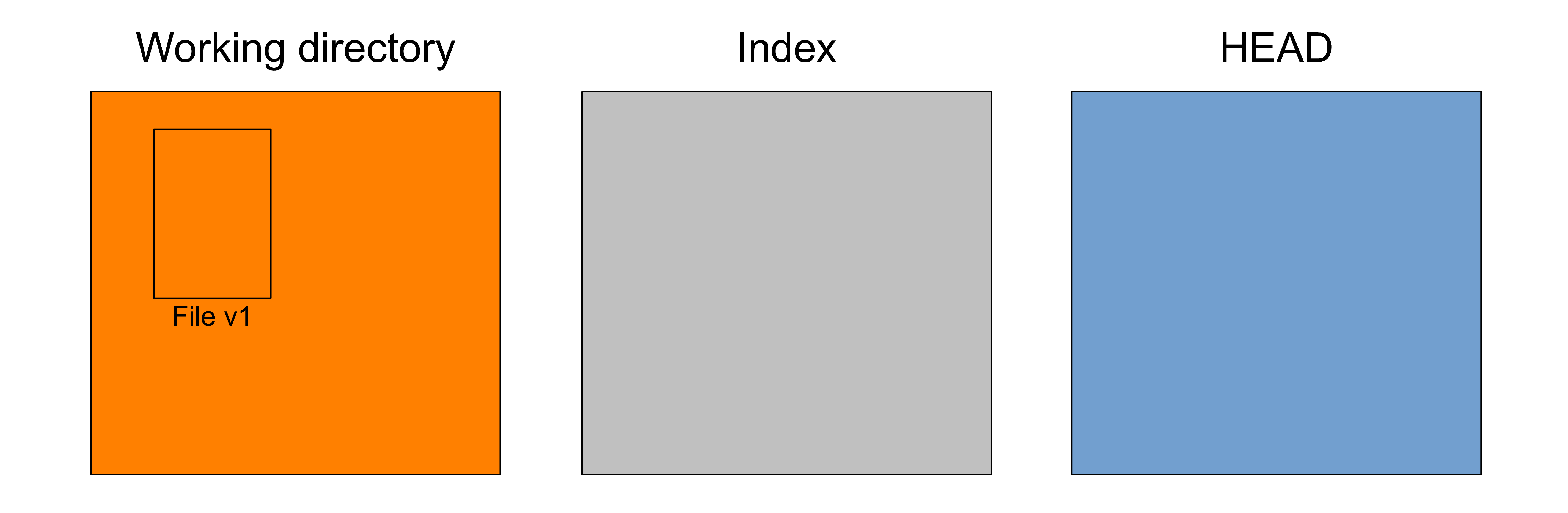

Let's create more selective snapshots¶

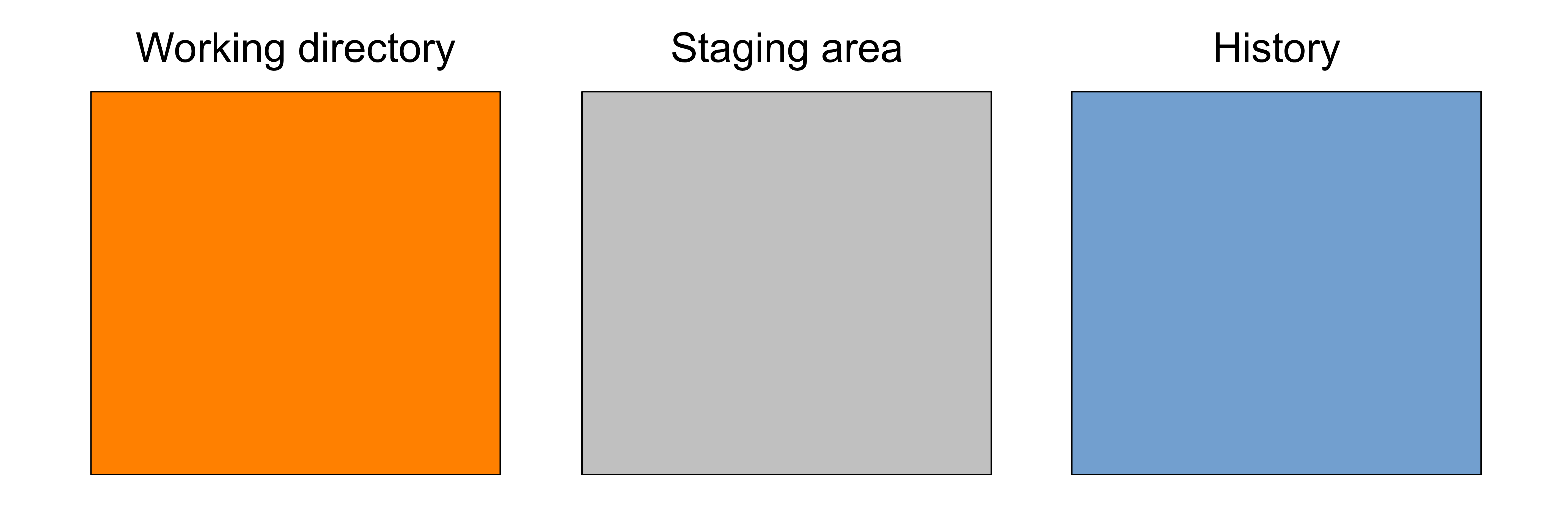

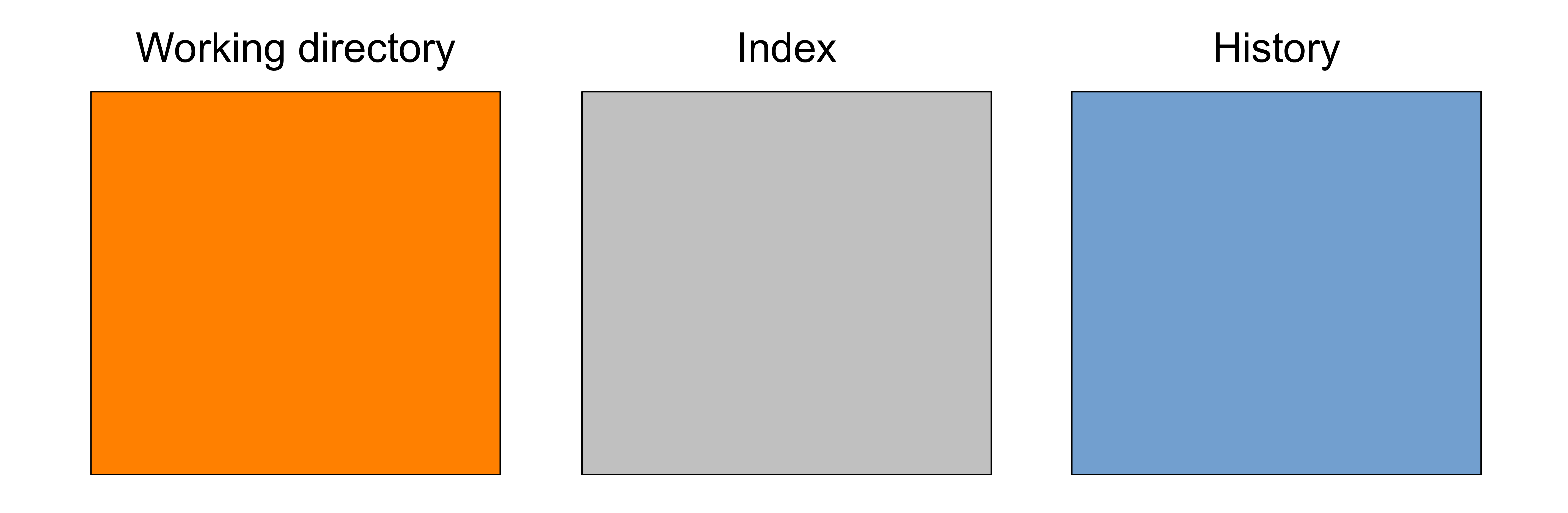

We made our first commit with:

git add .

git commit -m "Initial commit"

git add . stages all new changes in the repo.

It is even possible to commit all changes to the tracked files, staged or not, with git commit -a -m "Some message". With this command, you can thus skip the staging area entirely.

While these commands are convenient, you seldom want to do that: chances are, you'd be committing a mixed bag of changes that aren't grouped sensibly.

This creates a messy history that will be hard to navigate in the future (and will be hell for your collaborators).

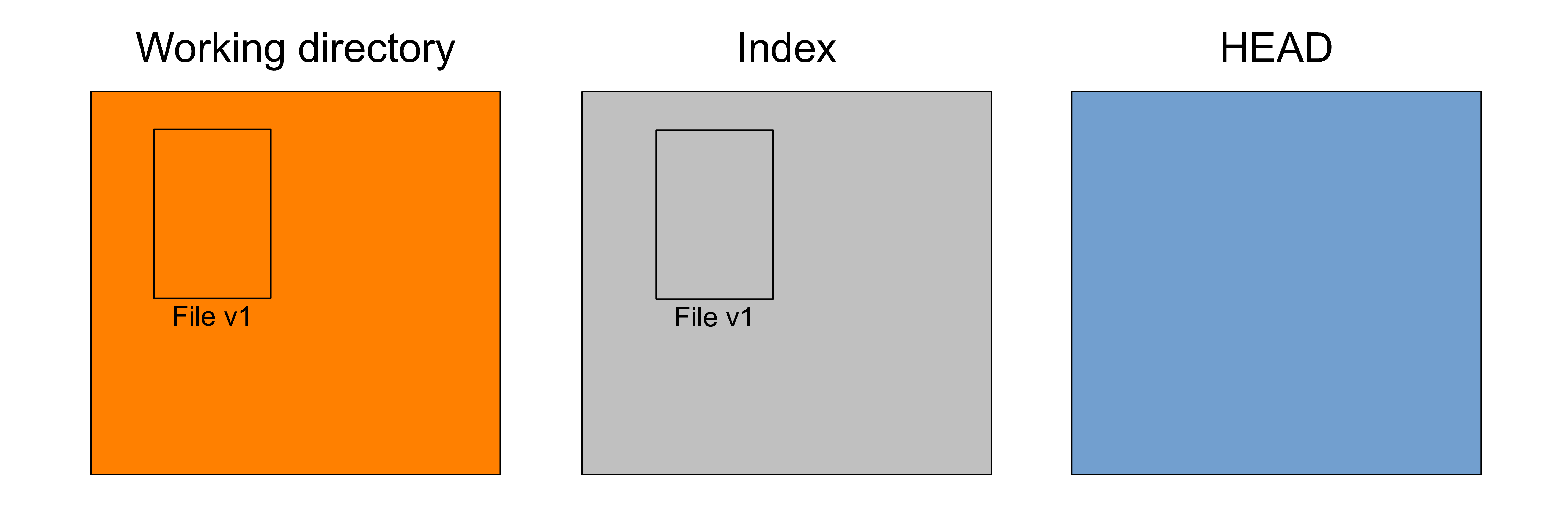

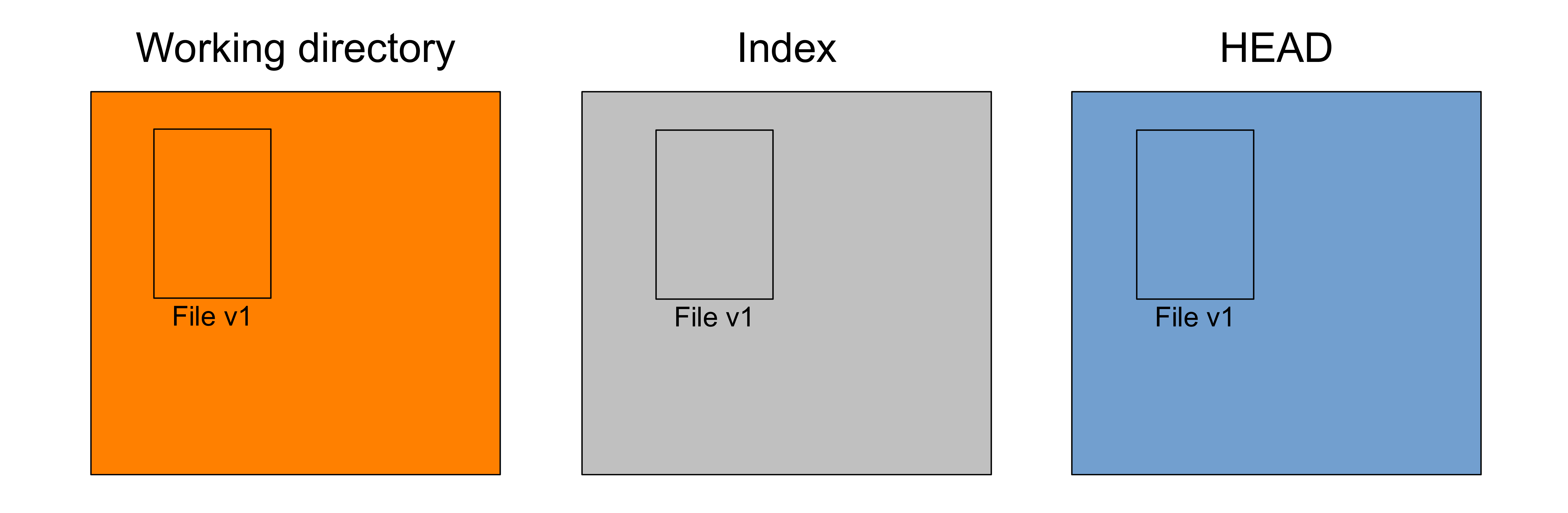

Recording history

Let's create more selective snapshots¶

What you want to do is to create commits that are meaningful.

This is why Git has this 2-step process to make snapshots:

- first you stage

- then you commit

The staging area allows you to pick and choose changes that you want to commit together.

Recording history

Let's create more selective snapshots¶

git add <file> allows you to only add the changes you made in <file> to the staging area (leaving changes to other files unstaged).

Even better, git add -p <file> allows you to stage only some of the changes made in <file>.

This gives you entire control over your recording of history.

Recording history

Let's create more selective snapshots¶

git add -p <file> starts an interactive staging session.

For each modified section (called "hunk"), Git will ask you:

y yes (stage this hunk)

n no (don't stage this hunk)

a all (stage this hunk and all subsequent ones in this file)

d do not stage this hunk nor any of the remaining ones

s split this hunk (if possible)

e edit

? print helpgit status

echo "# Effect of Enso on SST in the North Pacific between the years 2001 and 2020

## Introduction

## Methods

## Results

## Conclusion" > ms/enso_effect.md

git status

git add ms/enso_effect.md

git status

git commit -m "Add first draft enso effect ms"

git status

echo "Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe" >> ms/enso_effect.md

git status

echo "Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun

The frumious Bandersnatch" >> src/enso_model.py

git status

git add ms/enso_effect.md

git status

git commit -m "Add Jabberwock 1st paragraph to the enso effect ms"

git status

emacsclient -c ms/enso_effect.md

git status

(run from cli): git add -p ms/enso_effect.md

git status

git add src/enso_model.py

git status

git commit -m "Edits intro and conclusion ms

First draft intro Jabberwock

Format conclusion and rephrase last paragraph"

git status

git add .gitignore

git status

git commit -m "Add .gitignore with result dir"

git status

git commit -a -m "Add methods and result ms"

git status

echo "Add content to the ms" >> ms/enso_effect.md

git status

git commit -a -m "Minor edits enso model ms"

echo "Add code to the script" >> src/enso_model.py

git status

git commit -a -m "Minor edits script"

git status

Recording history

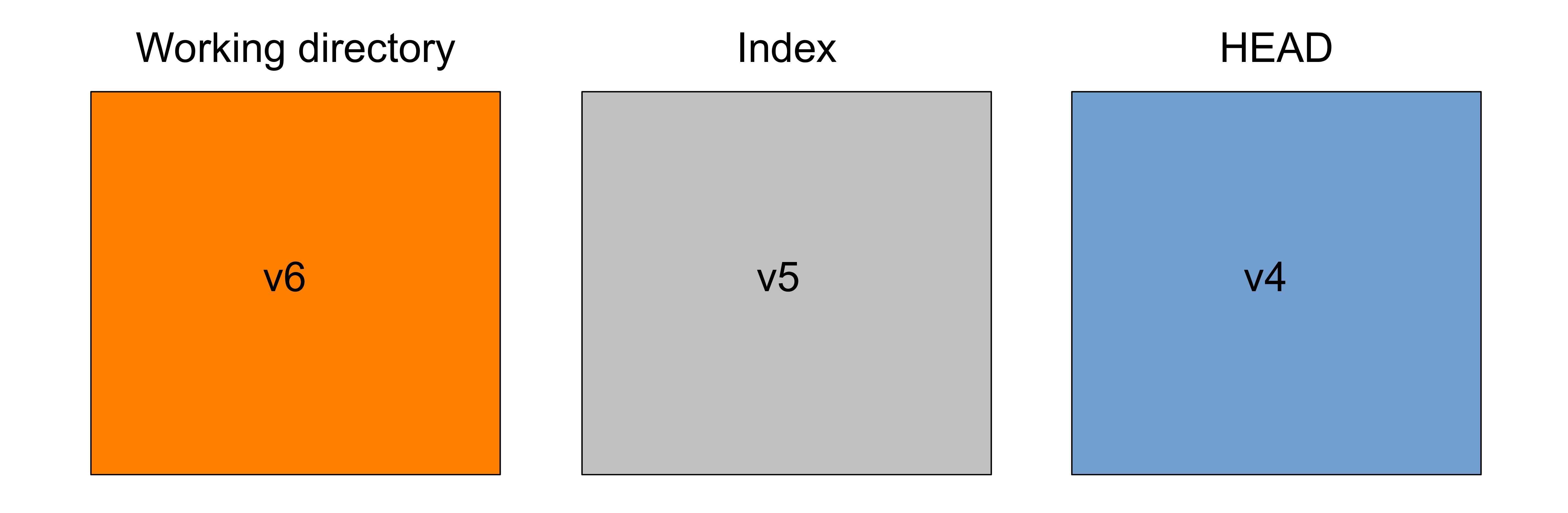

Inspecting changes¶

We saw that git status is the key command to get information on the current state of the repo.

While this gives us the list of new files and files with changes, it doesn't allow us to see what those changes are. For this, we need git diff.

git diff shows changes between any two elements (e.g. between commits, between a commit and your working tree, between branches, etc.).

git status

echo "Adding some ending to the ms" >> ms/enso_effect.md

echo "Adding more code to the script" >> src/enso_model.py

git add ms/enso_effect.md

git status

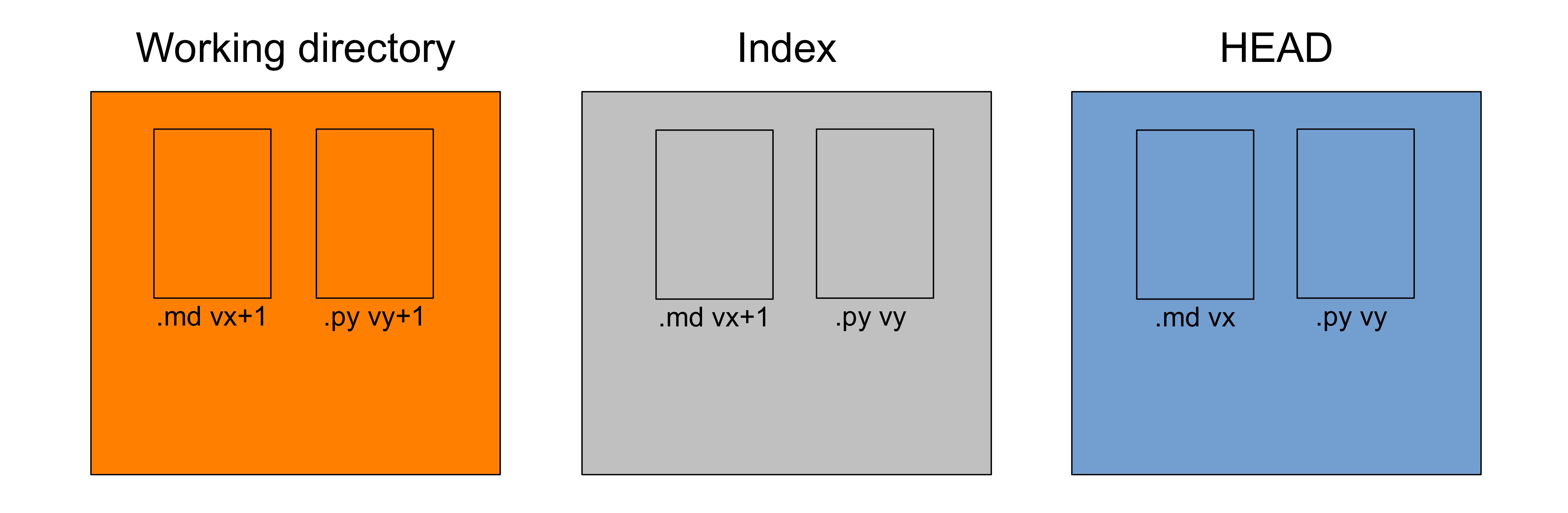

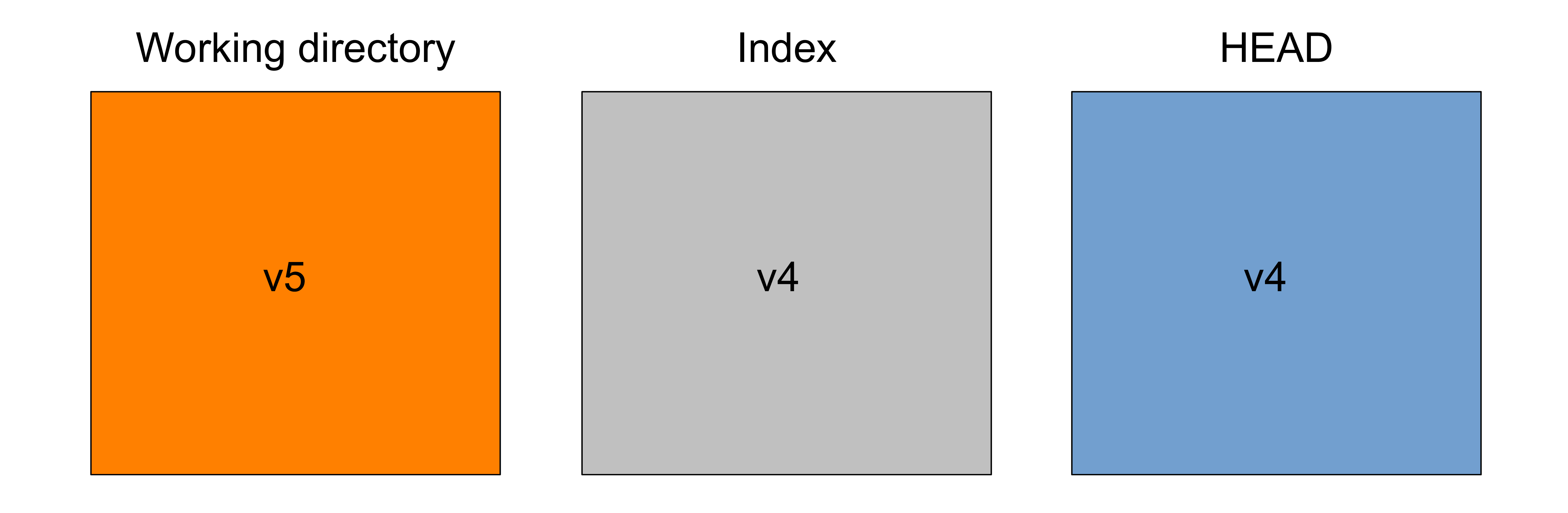

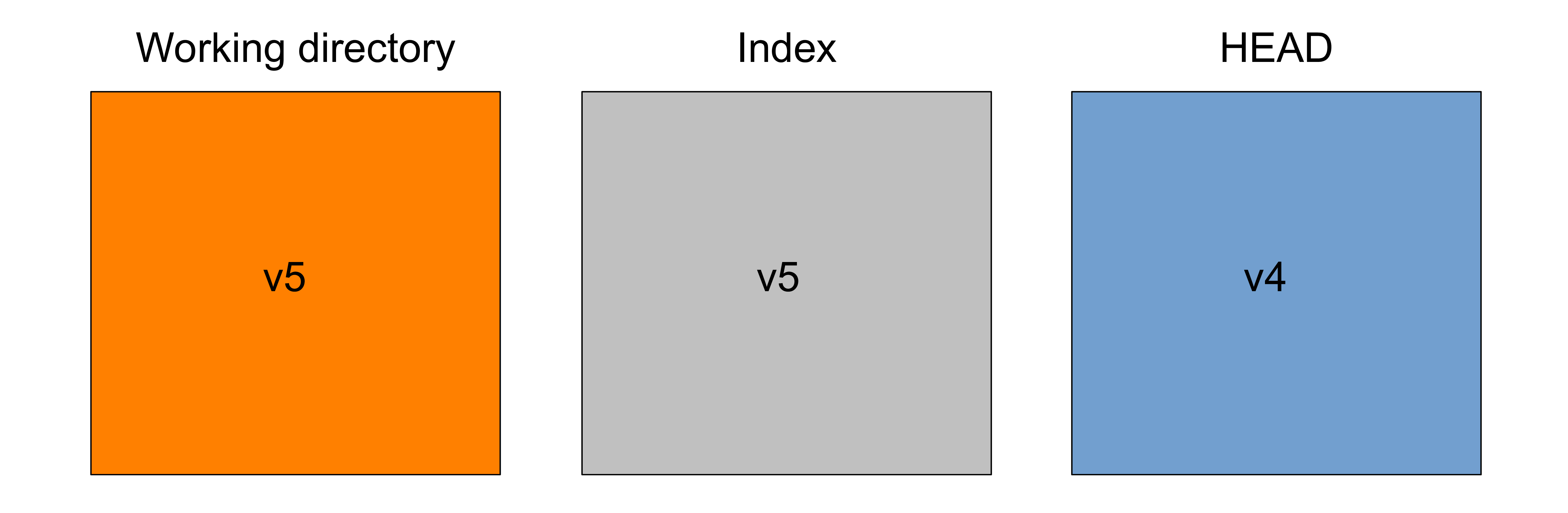

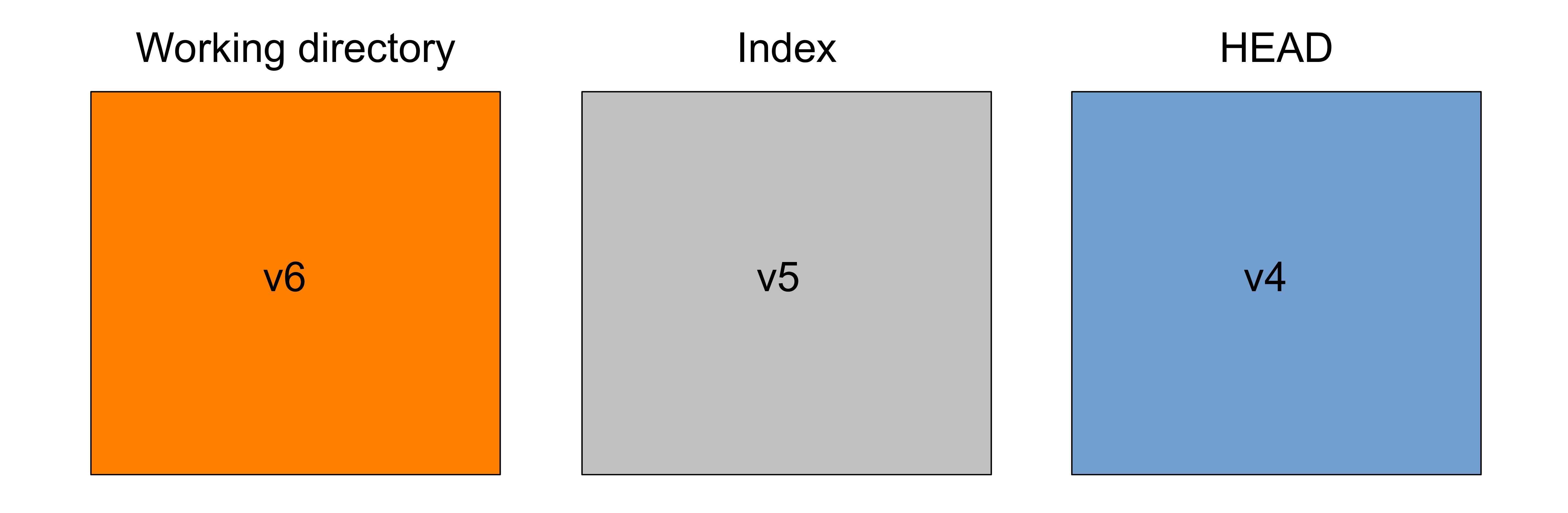

**Under the hood**

Recording history

Inspecting changes¶

Difference between the working directory and the index¶

That's all your unstaged changes on tracked files.

Git can see new files you haven't staged: it lists them in the output of git status. Until you put them under version control by staging them for the first time however, Git has no information about their content: at this point, they are untracked and they are not part of the working tree yet. So their content never appears in the output of git diff.

**Under the hood**

Recording history

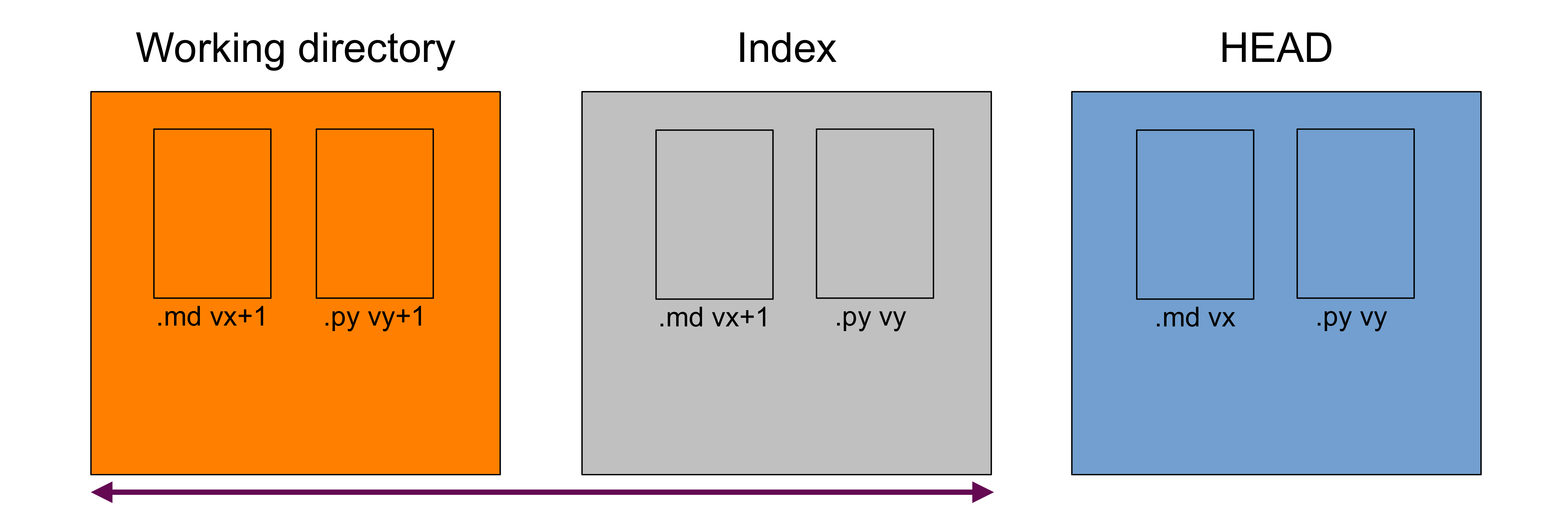

git diff

**Under the hood**

Recording history

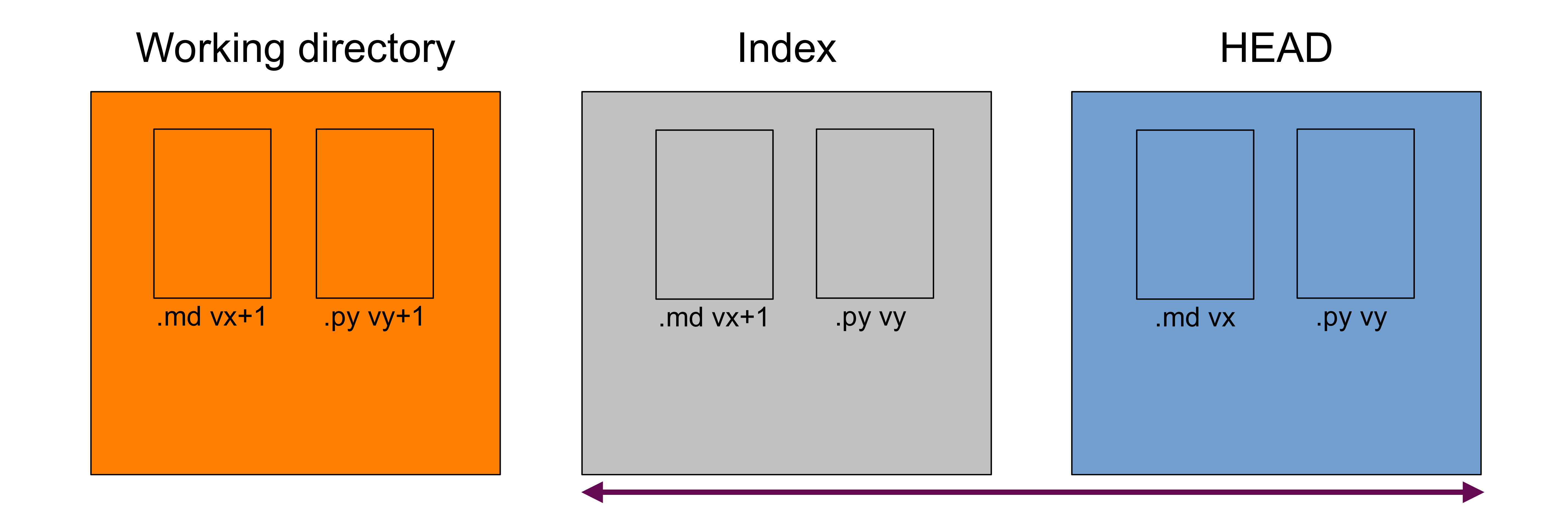

git diff --cached

**Under the hood**

Recording history

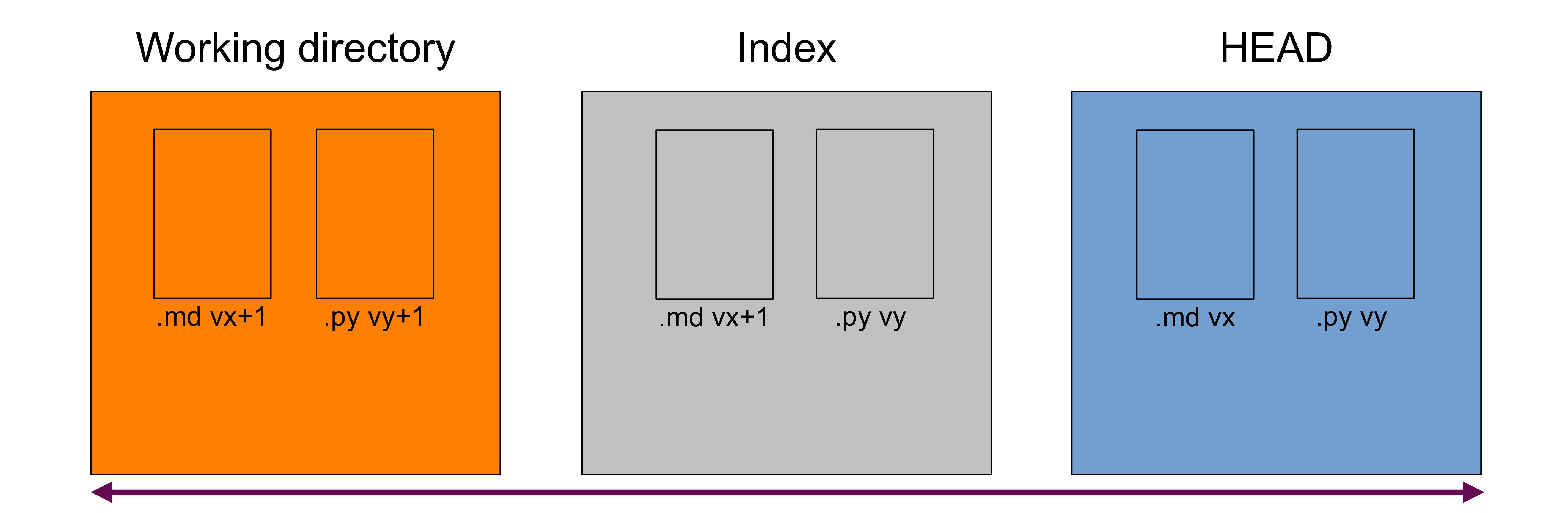

git diff HEAD

echo "Manuscript on long-term acidity change in the Pacific" > ms/acidity.md

git status

git diff HEAD

git diff HEAD~ HEAD

git diff HEAD HEAD~

git rev-parse HEAD

git rev-parse --short HEAD

git rev-parse --short HEAD~

git diff 265338c 62bfbea

git --no-pager diff HEAD

Recording history

Inspecting changes¶

git show shows one object. Applied to a commit, shows the log and changes made at that commit.

git show

git show HEAD

git show HEAD~

git show HEAD~2

git show HEAD~2 --oneline

Working with branches¶

Working with branches

Putting aside for a while (stashing)¶

Before moving HEAD around (amongst branches or in the past), make sure to have a clean working directory.

If you aren't ready to create a commit (messy, unfinished changes, etc.), you can stash those changes and retrieve them later.

git status

git stash -u # -u to include untracked files

git status

git stash list

git stash apply --index # --index to restage the files that were staged before

git stash drop # delete the stash

git stash list

git stash -u

git status

Working with branches

Putting aside for a while (stashing)¶

A few notes:

- You can apply a stash on a dirty directory

- You can apply a stash on another branch

- You can apply and drop a stash in one command with

git stash pop, but the--indexoption is not available - You can have several stashes. In that case, Git always assumes you want to perform an action on the last one. If that is not the case, you have to provide the name of the stash you want to use (e.g.

git stash apply stash@{1}. You can find that name withgit stash list).

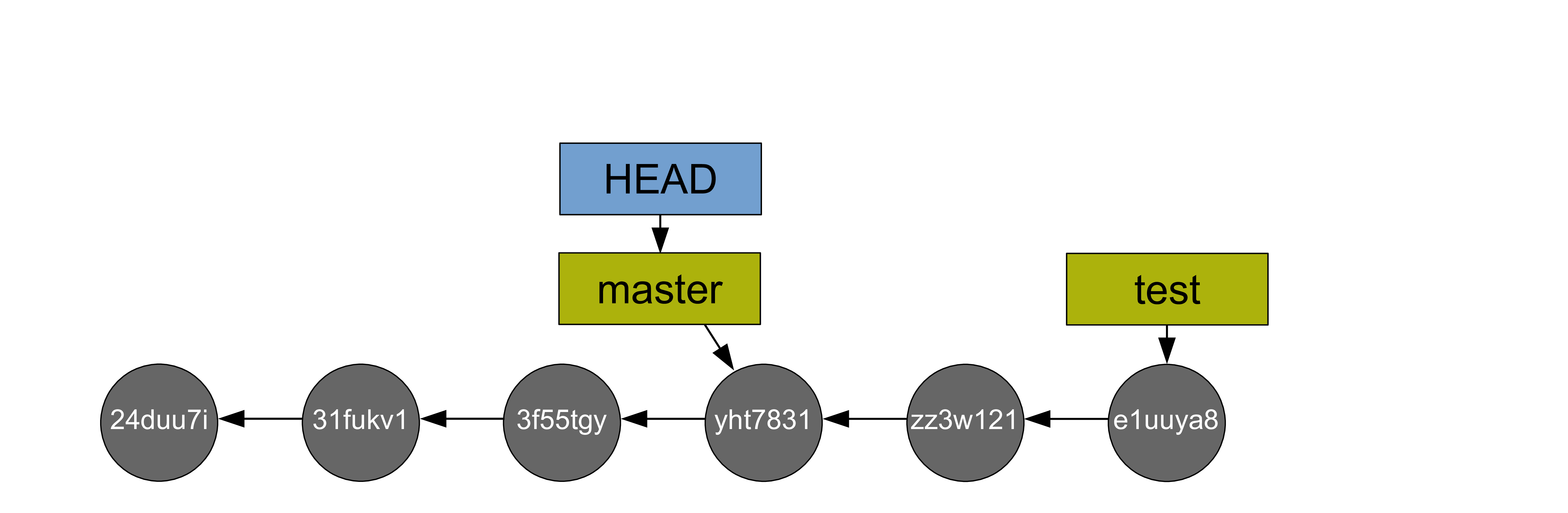

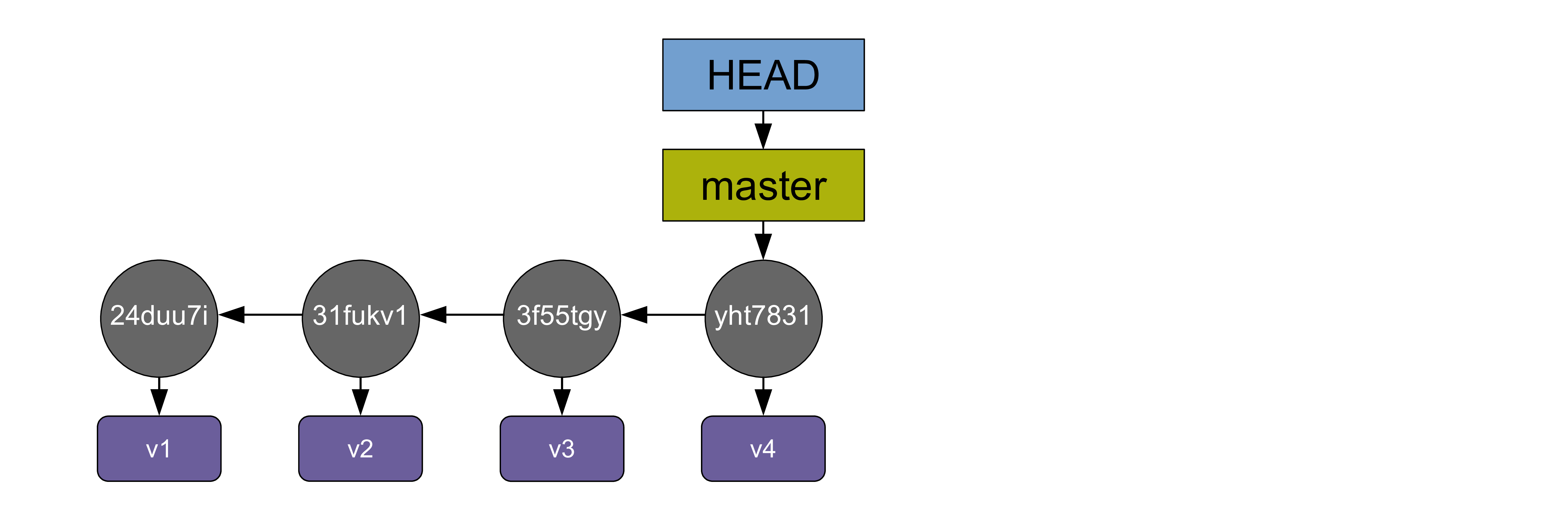

Working with branches

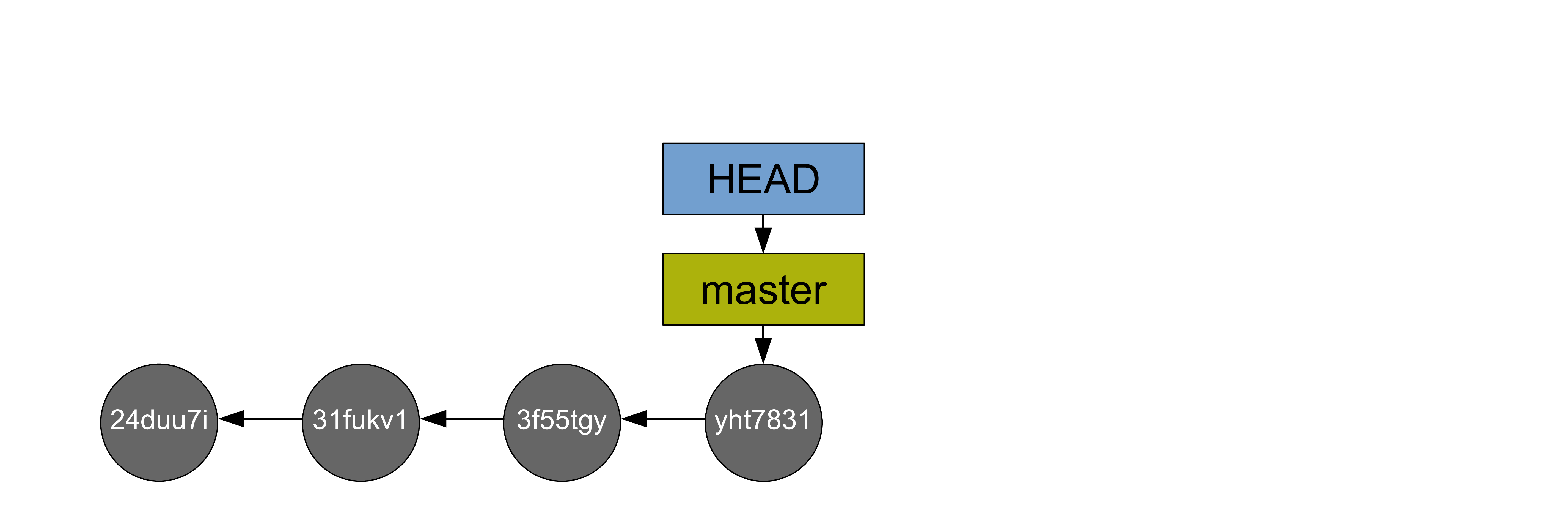

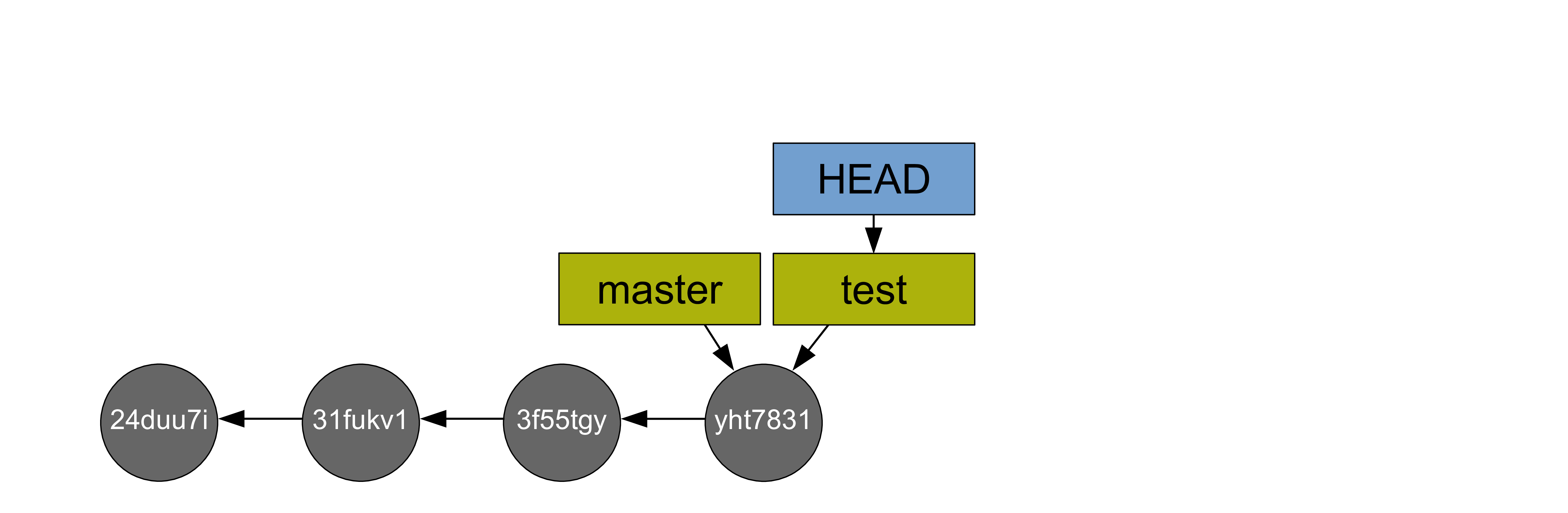

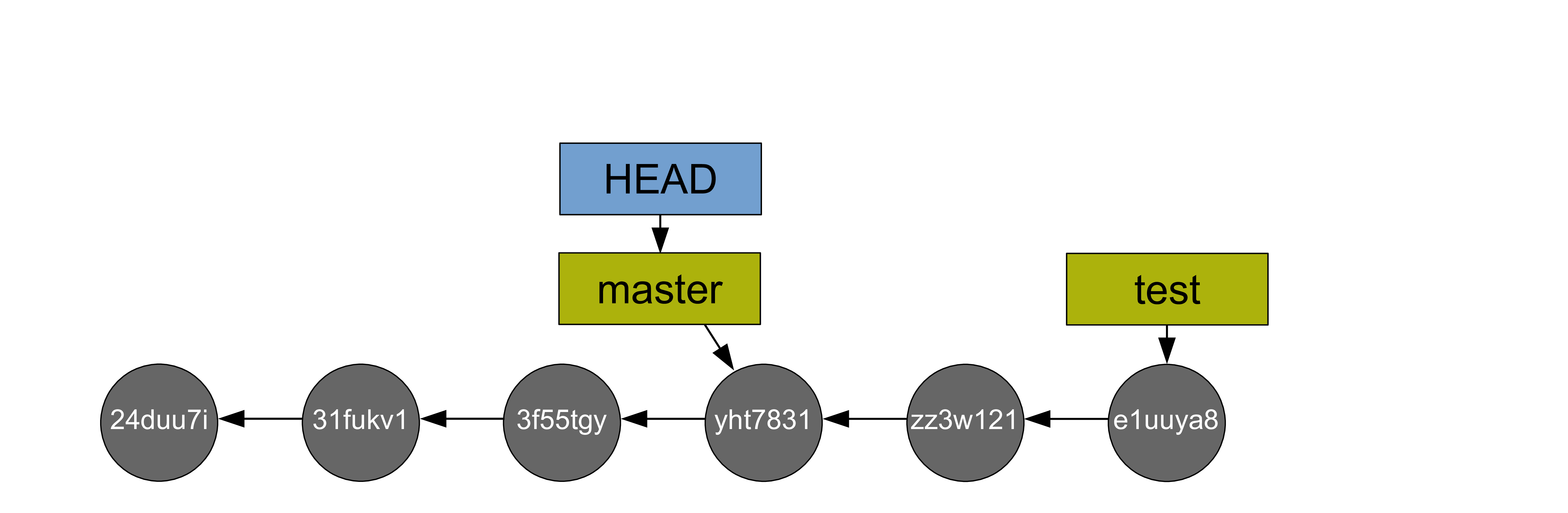

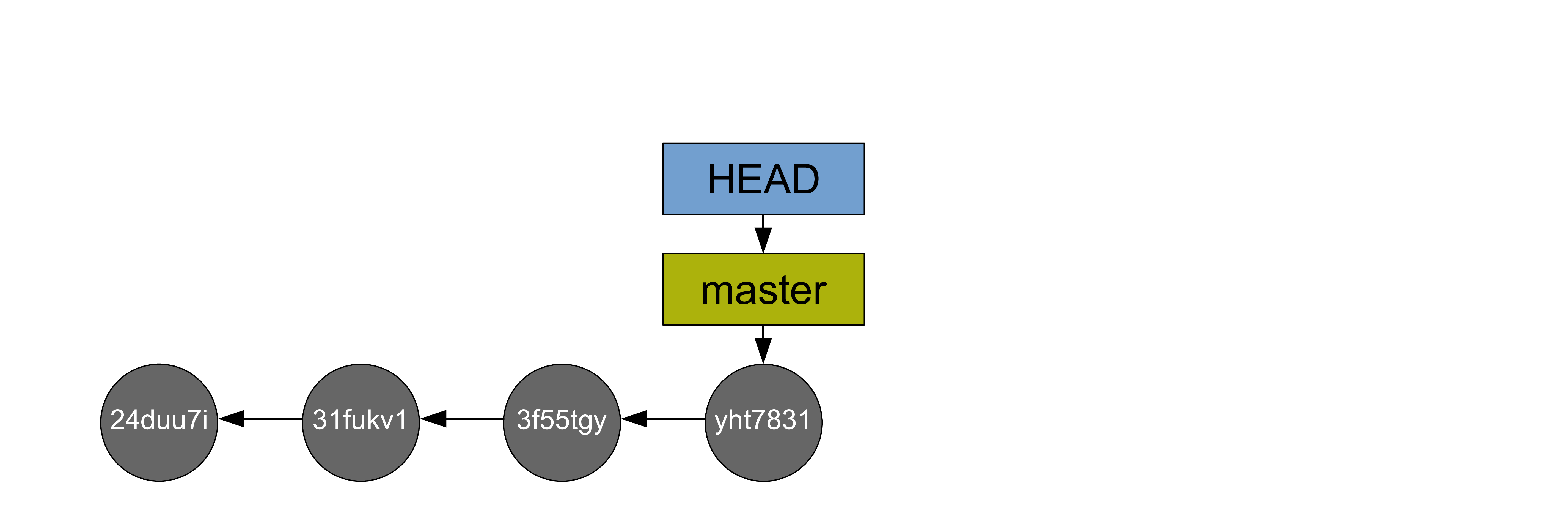

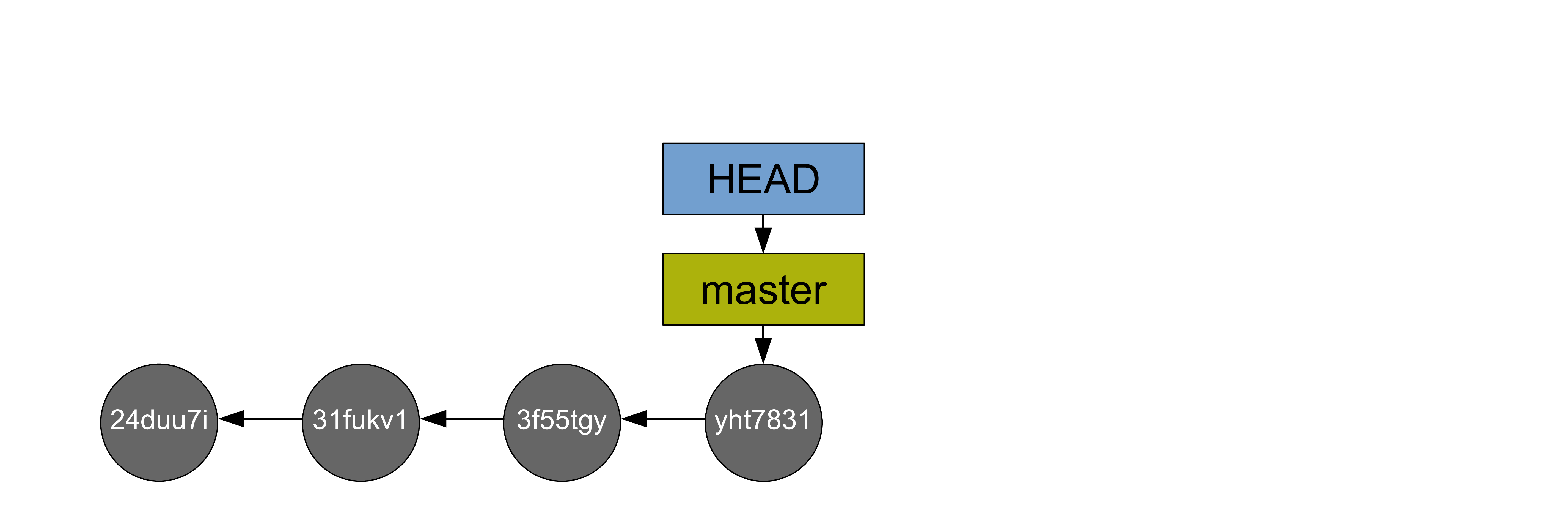

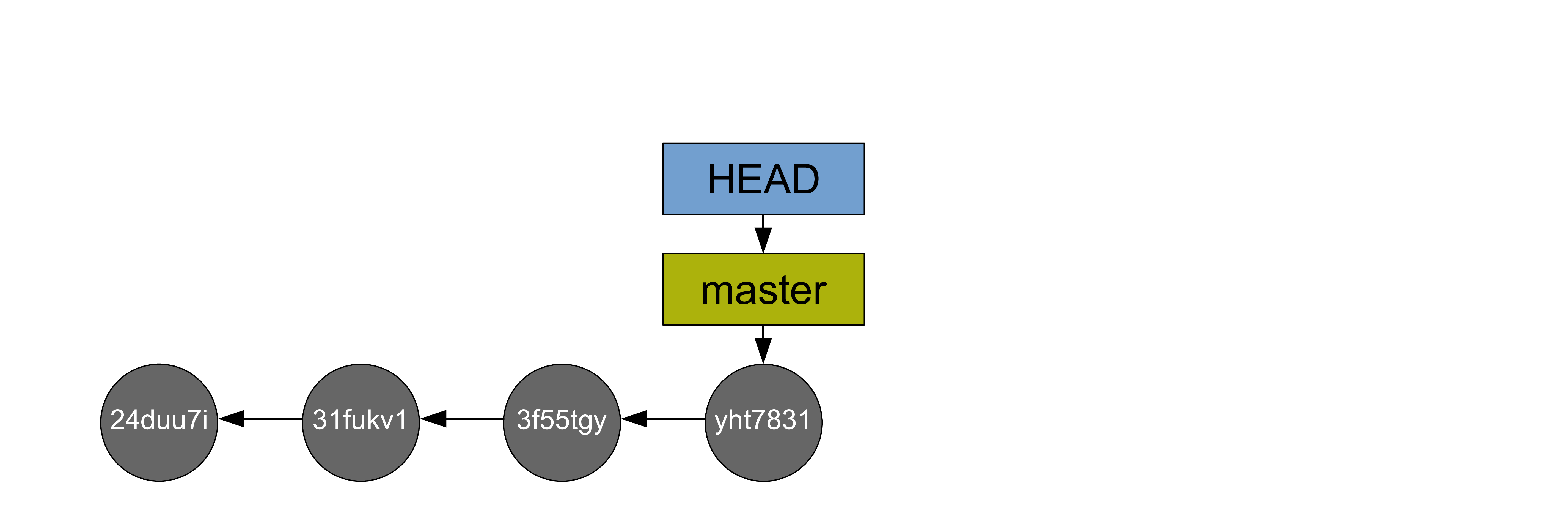

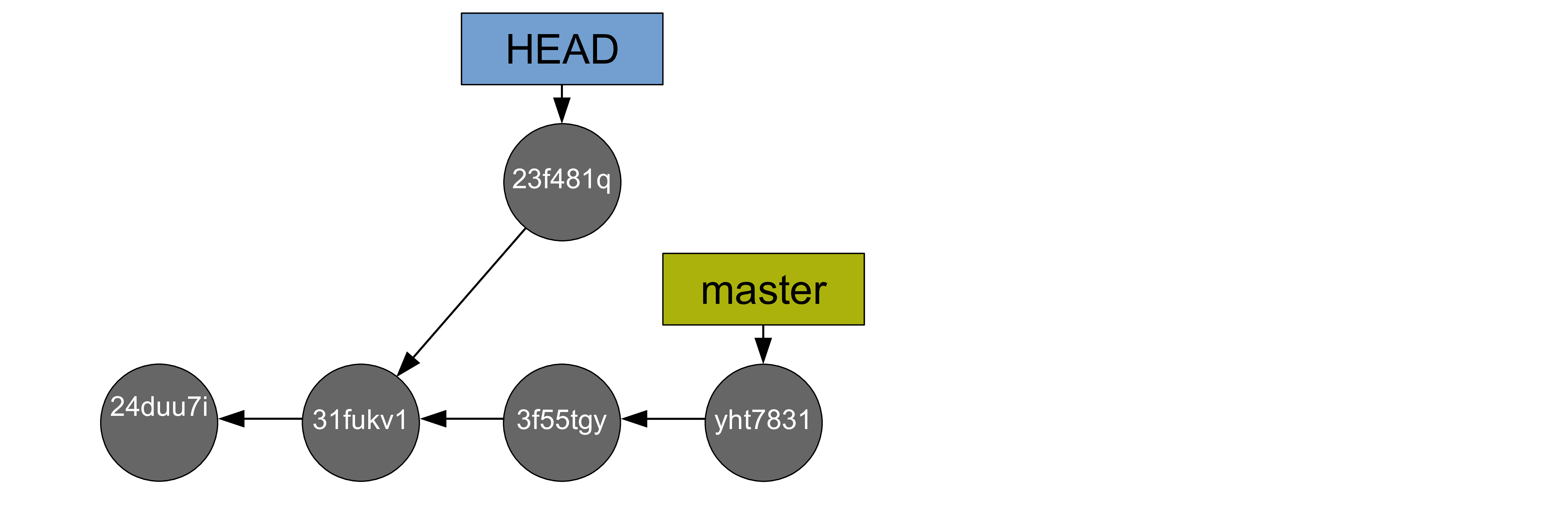

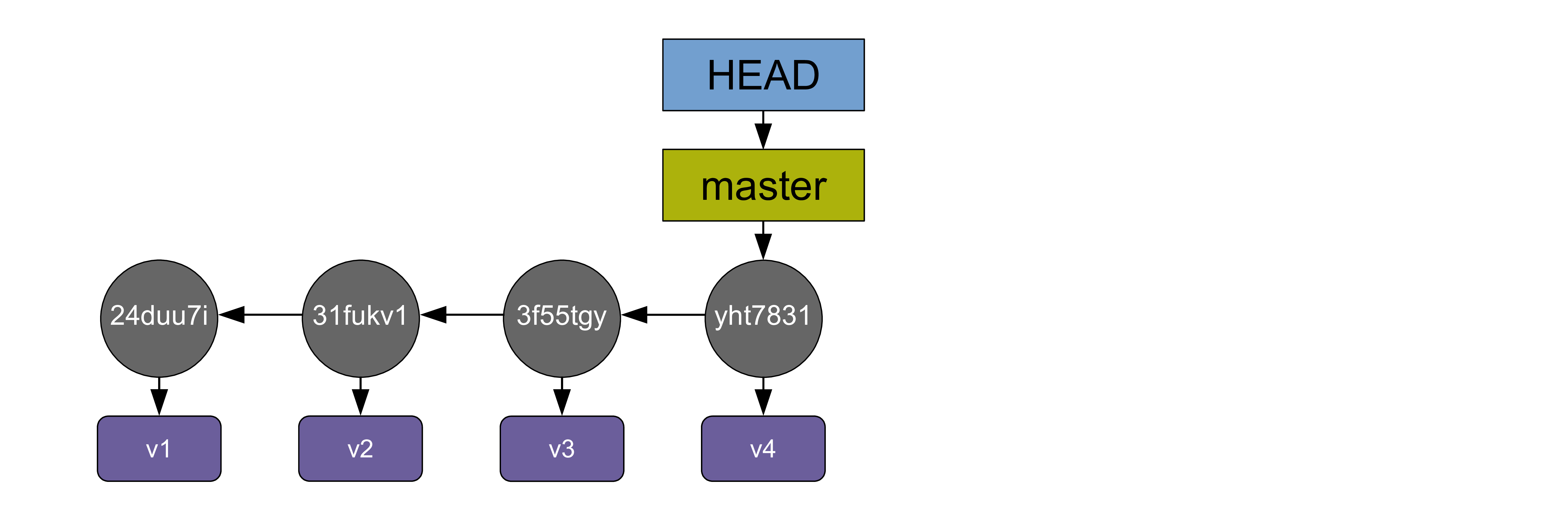

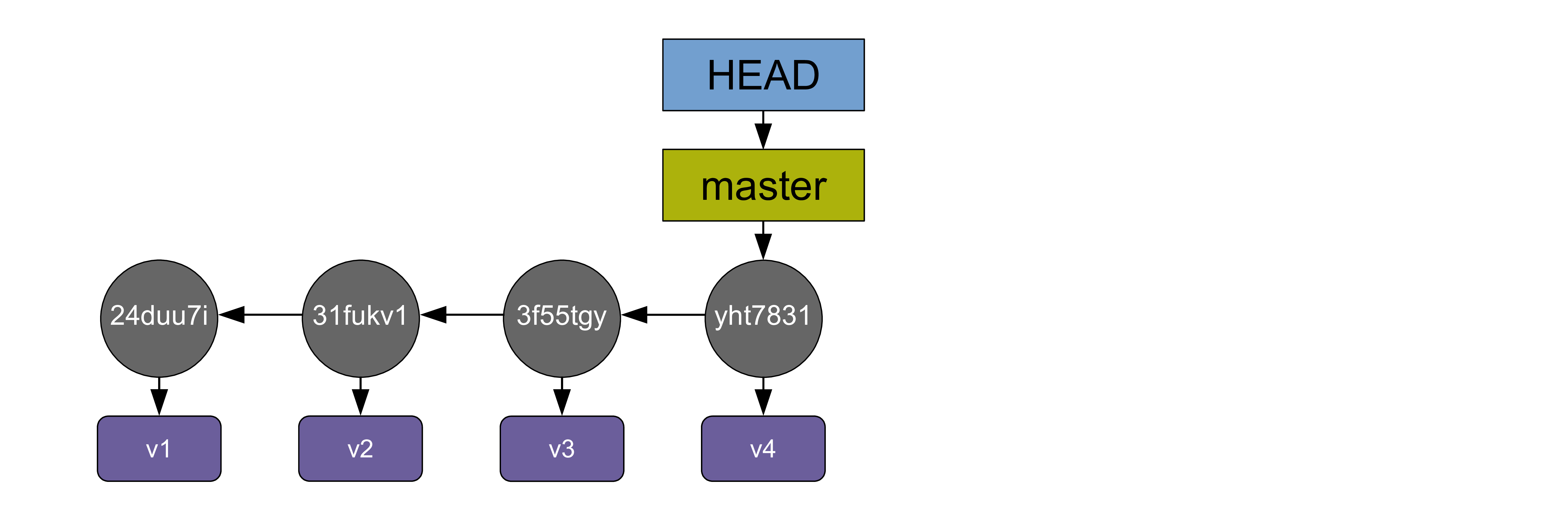

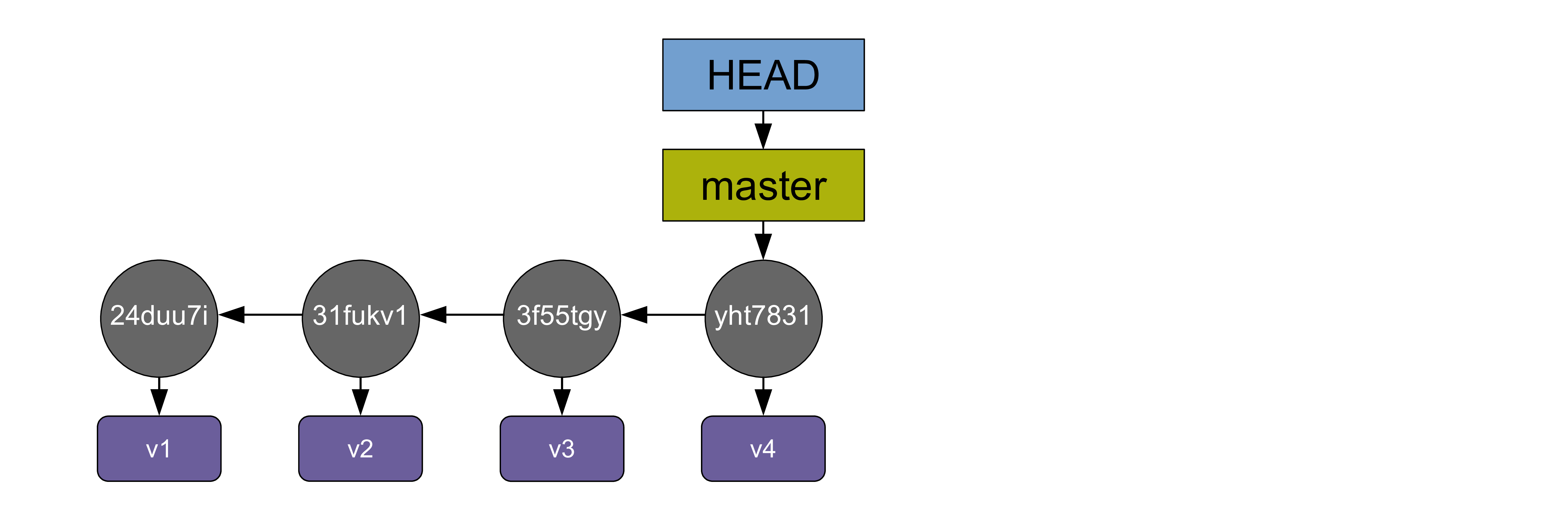

Creating branches¶

"master"¶

When you initialized your repository with git init, a branch got created. It is called master (you could rename it to something else if you wanted—that initial branch, despite its name, has nothing special).

So as soon as you start working on your project, there is one branch (master) and you are on it.

git branch

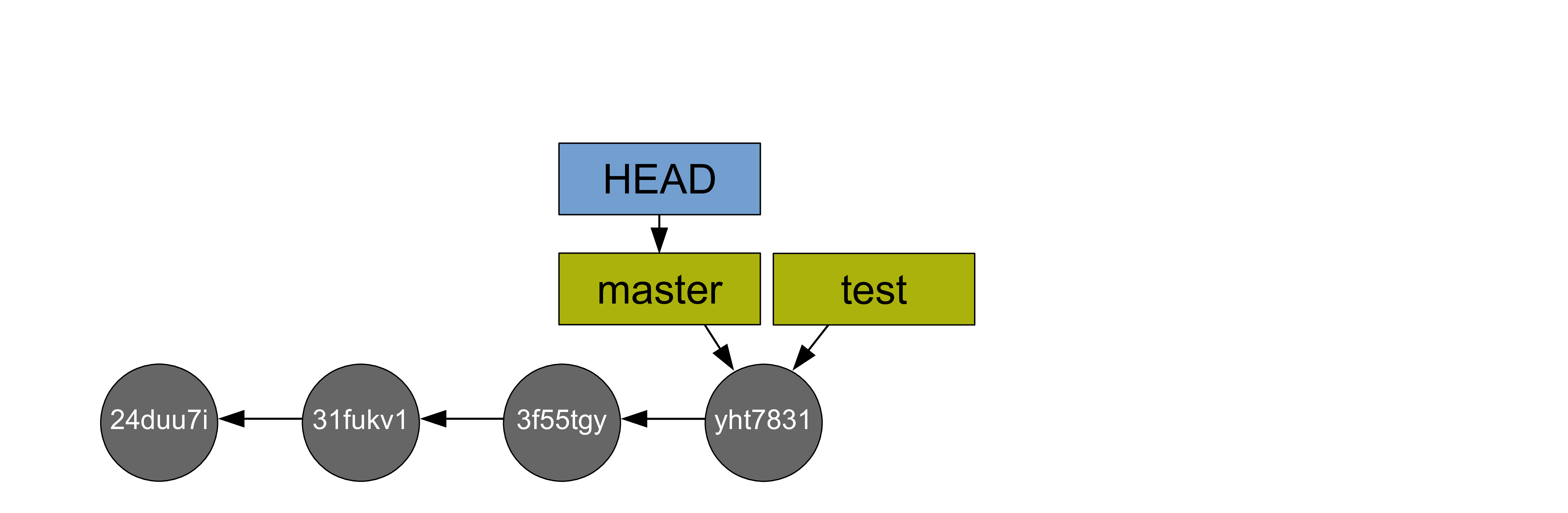

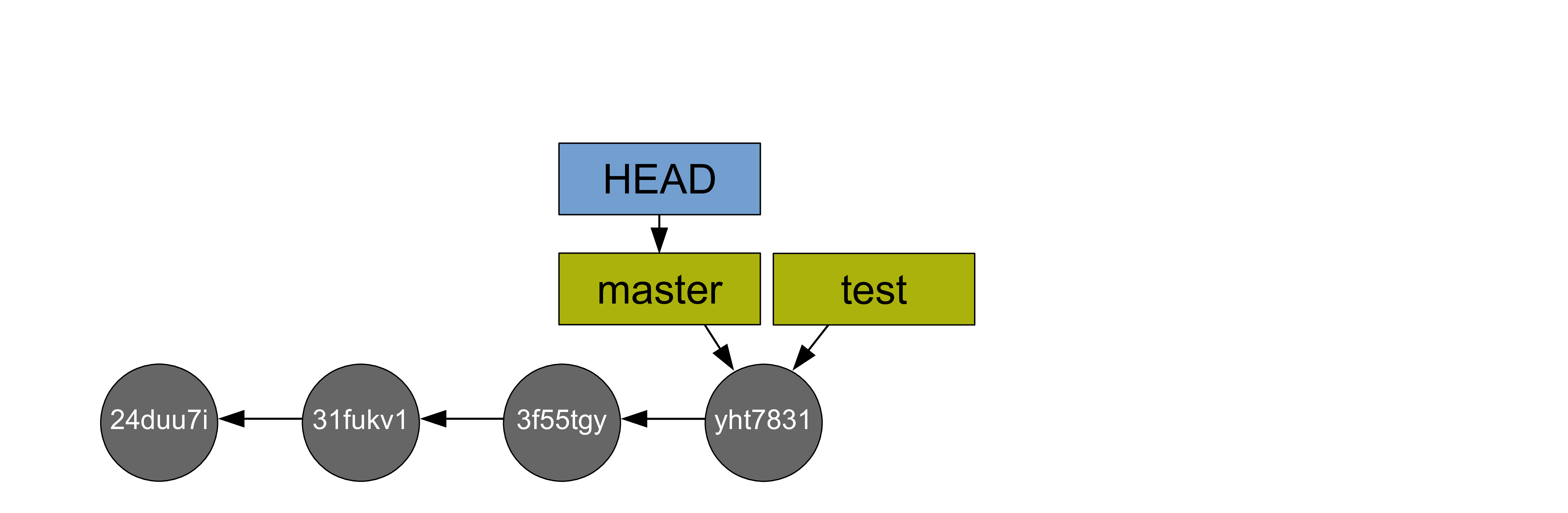

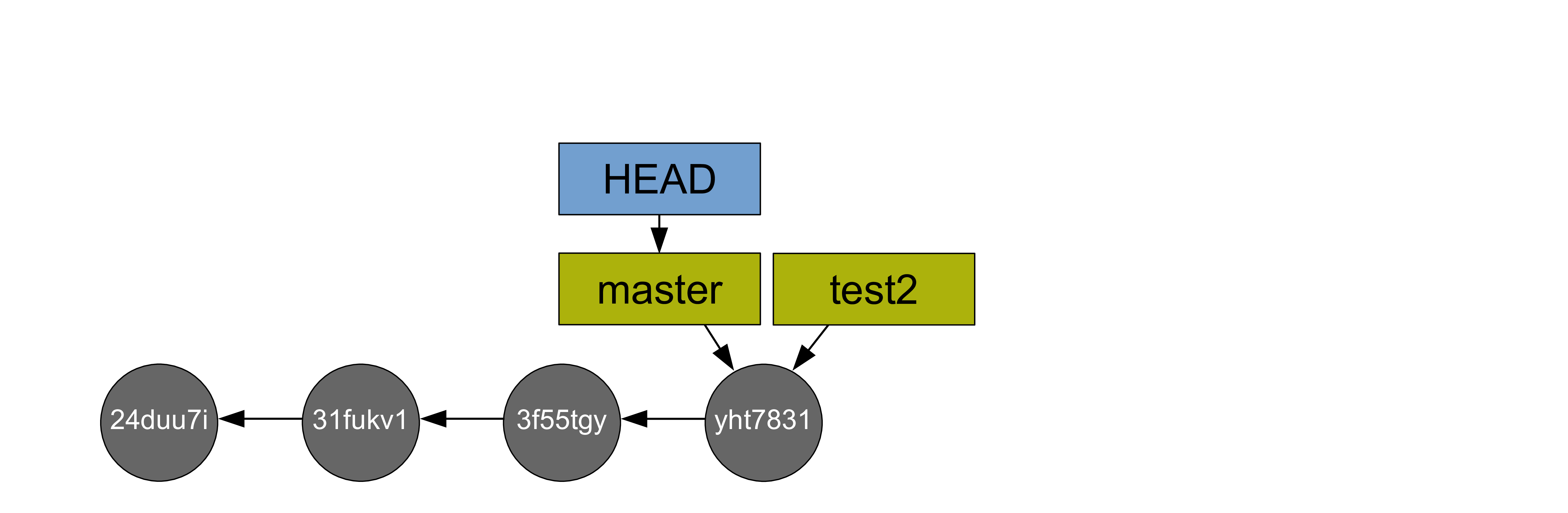

git branch test

git status

git branch

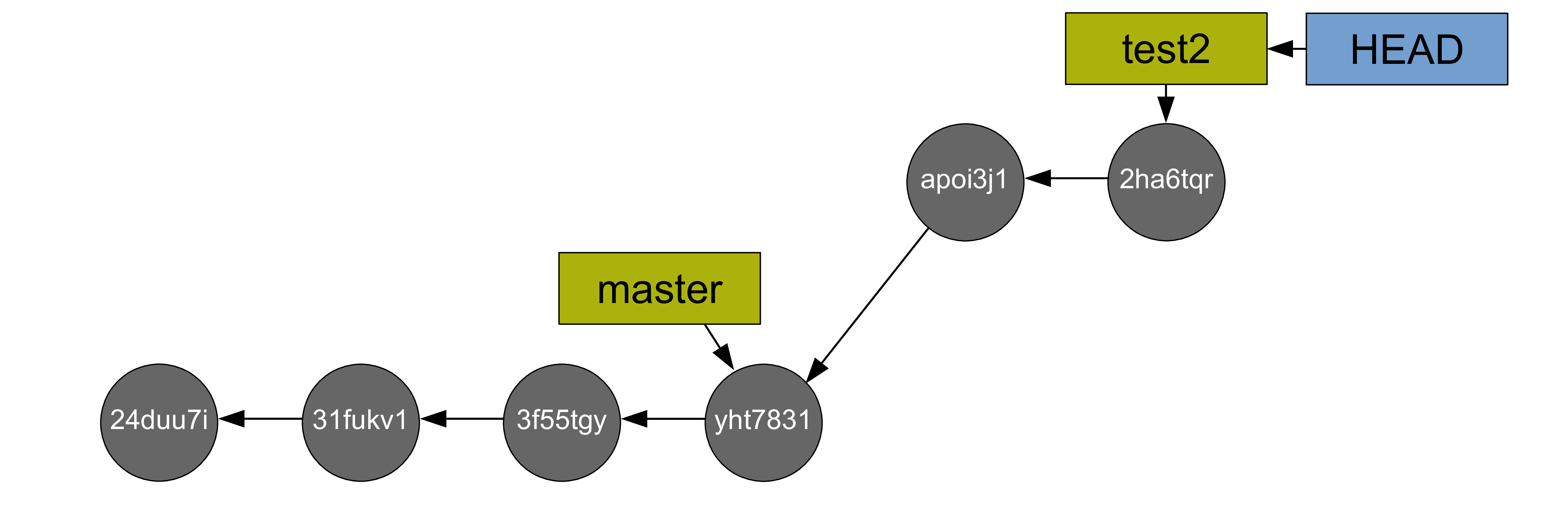

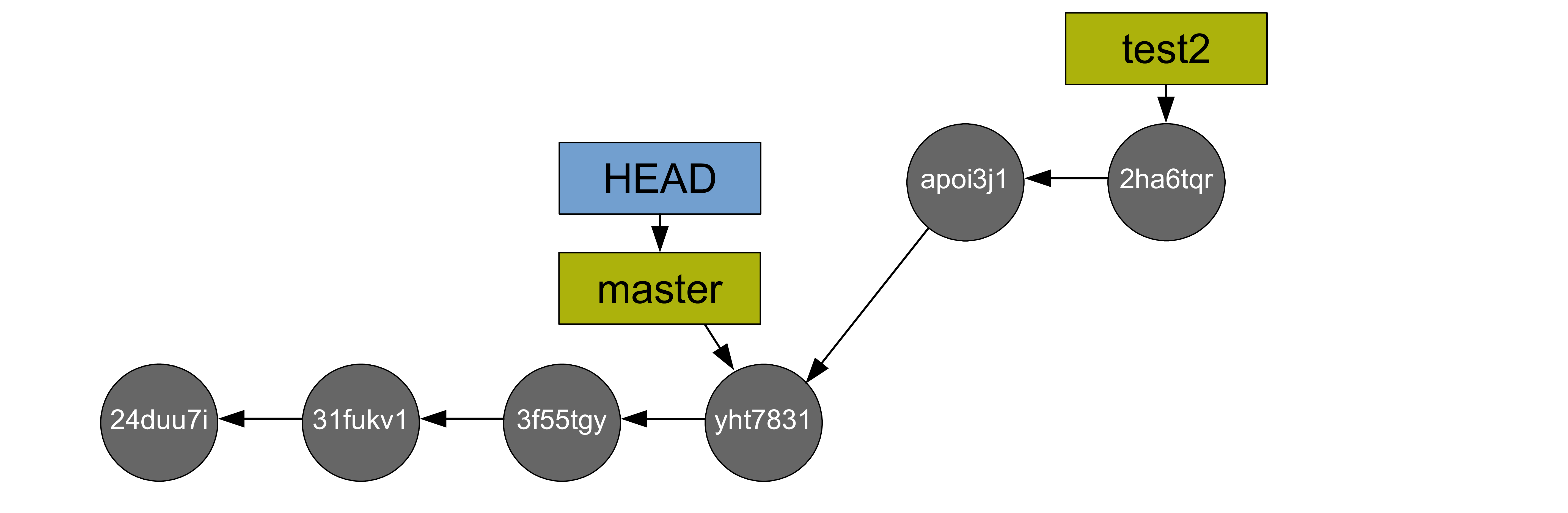

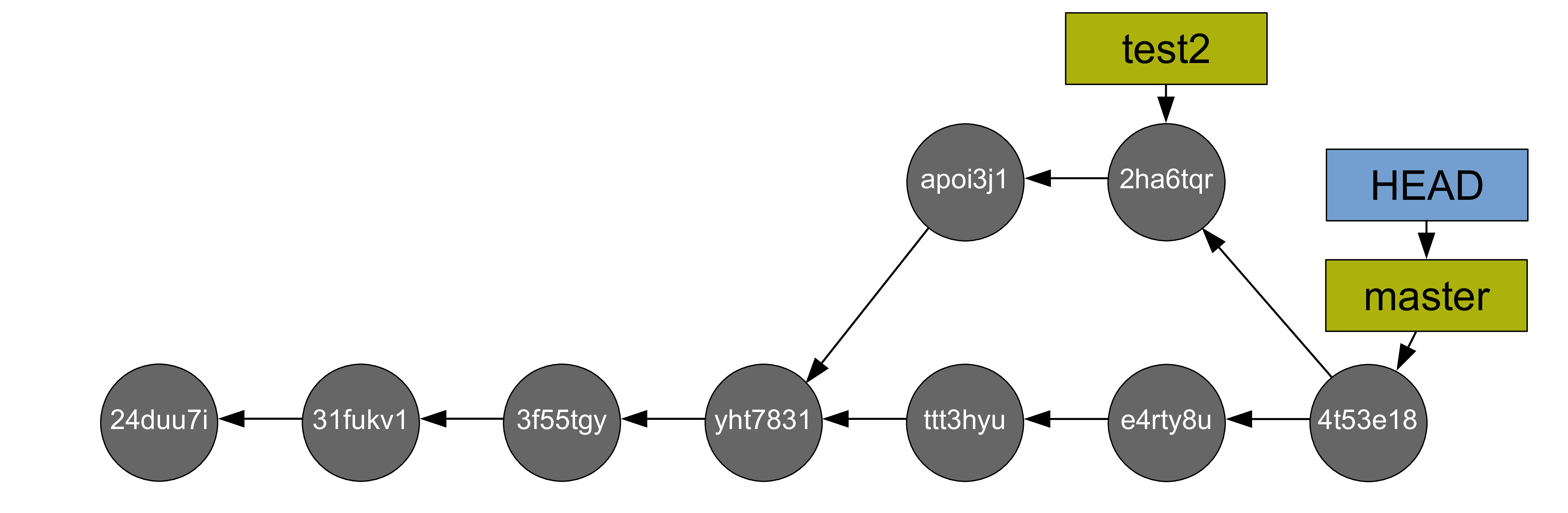

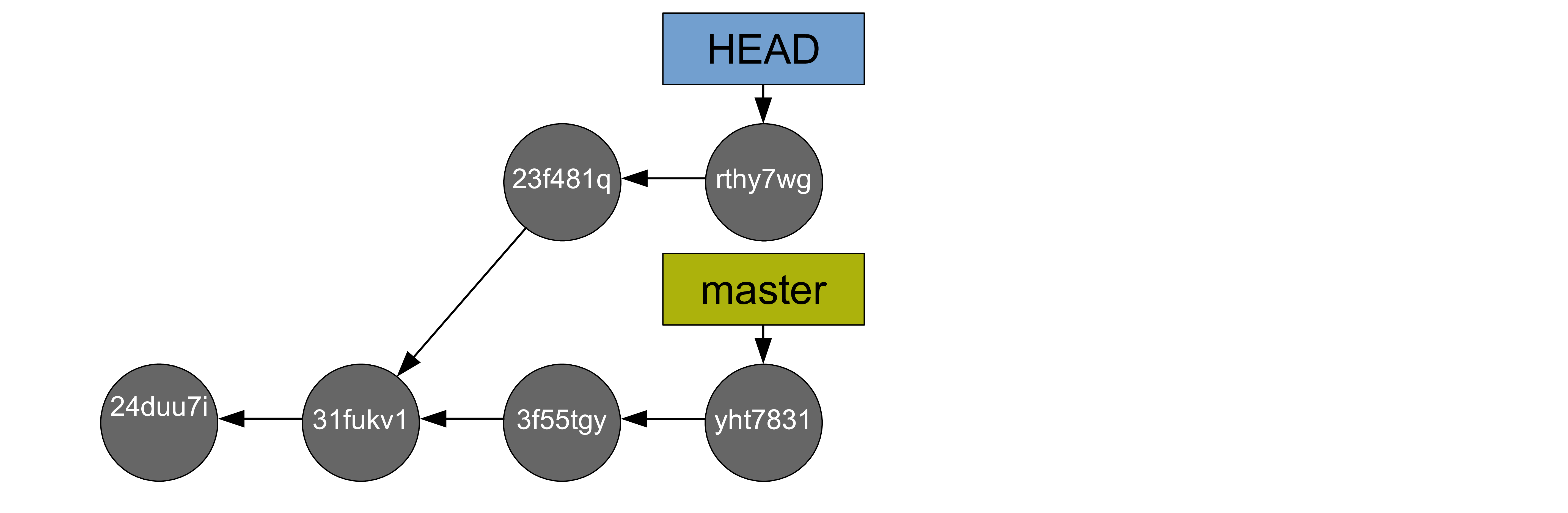

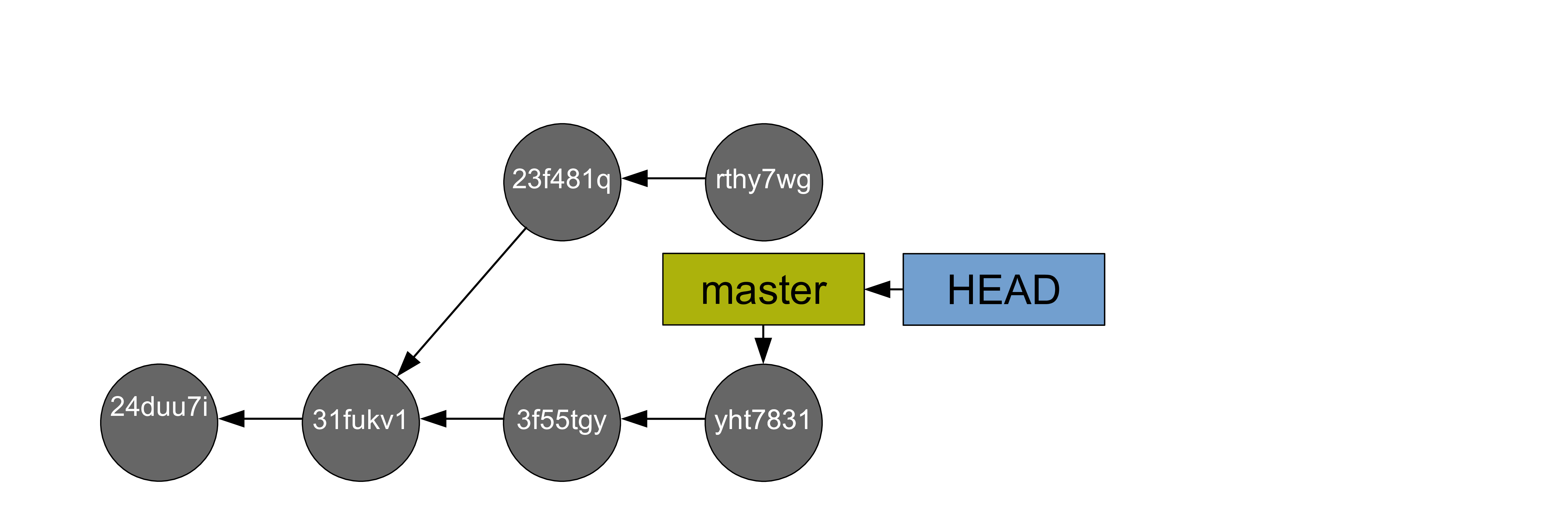

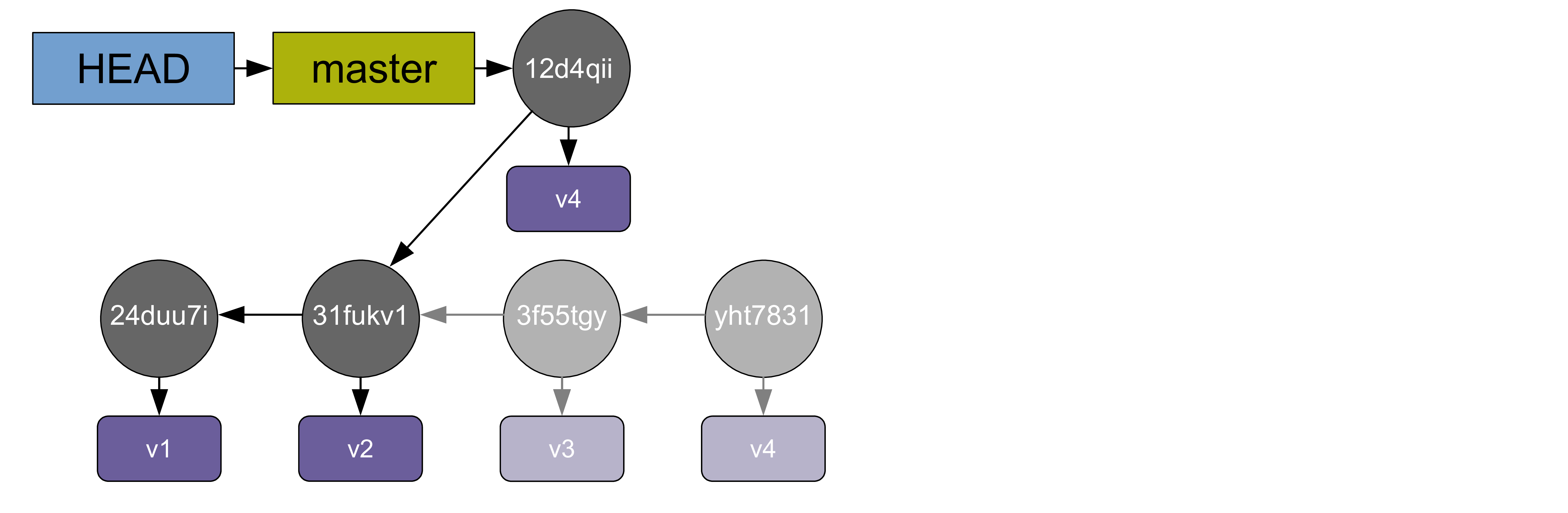

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

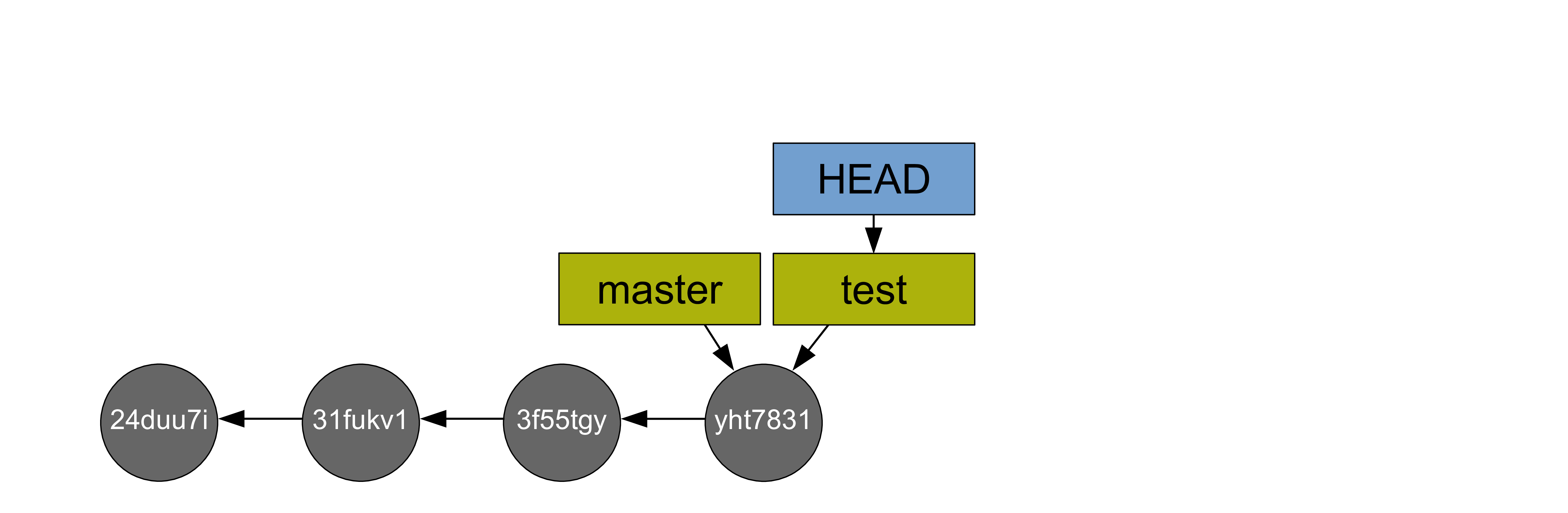

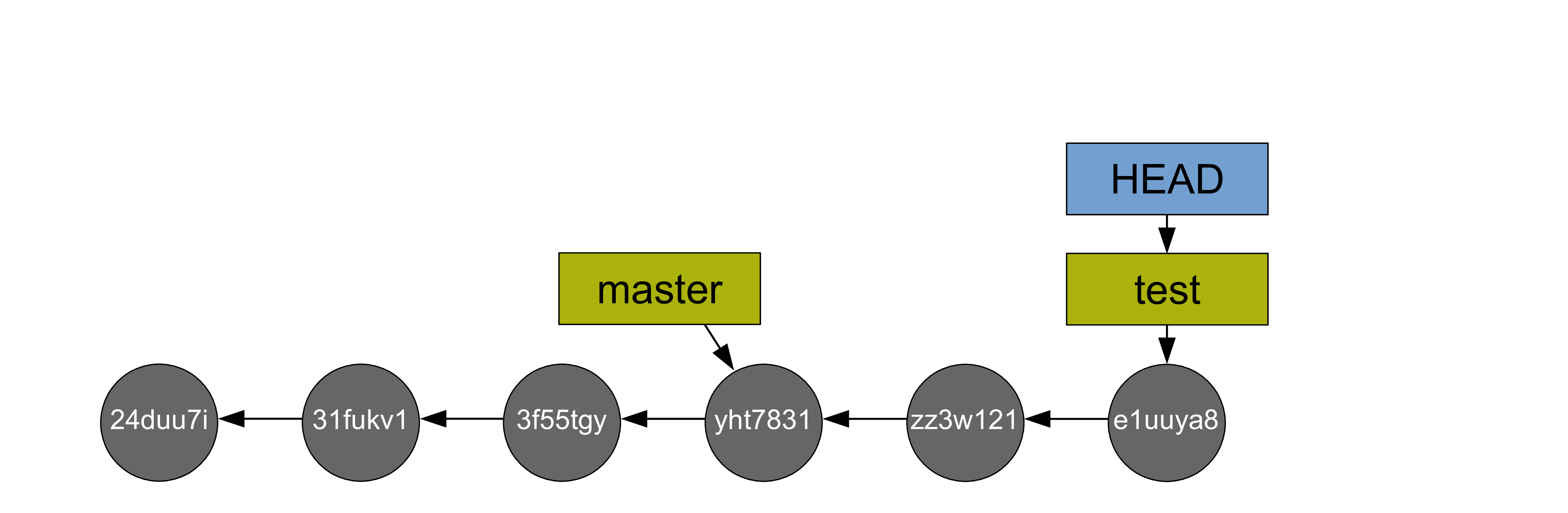

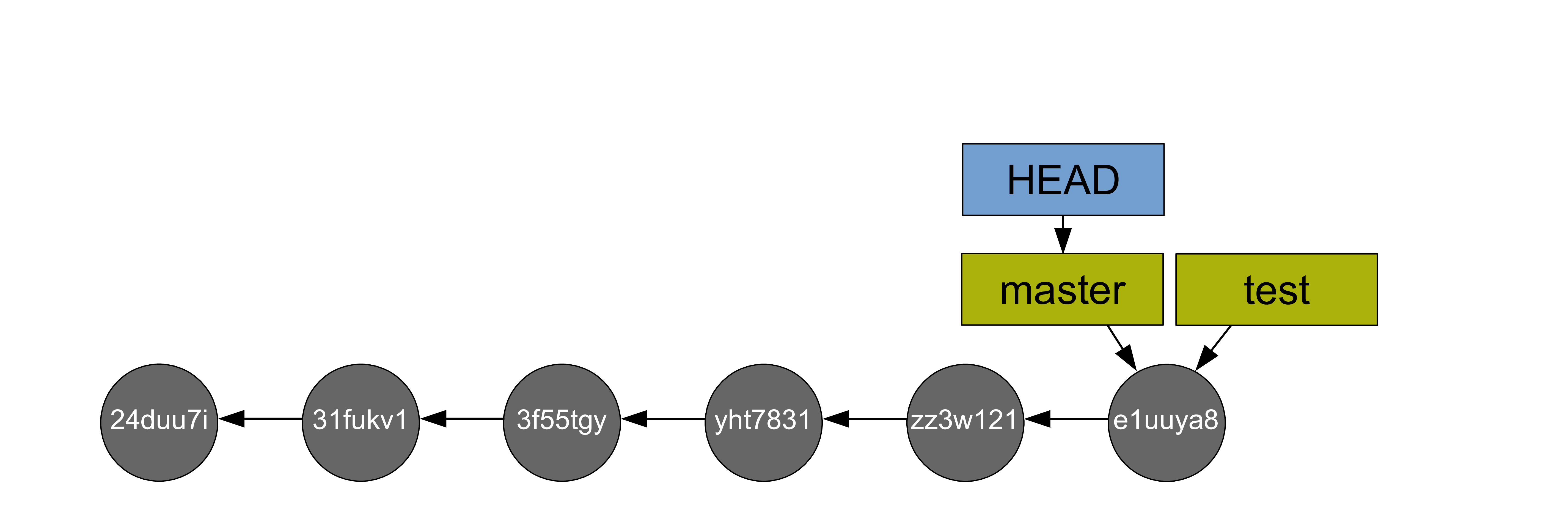

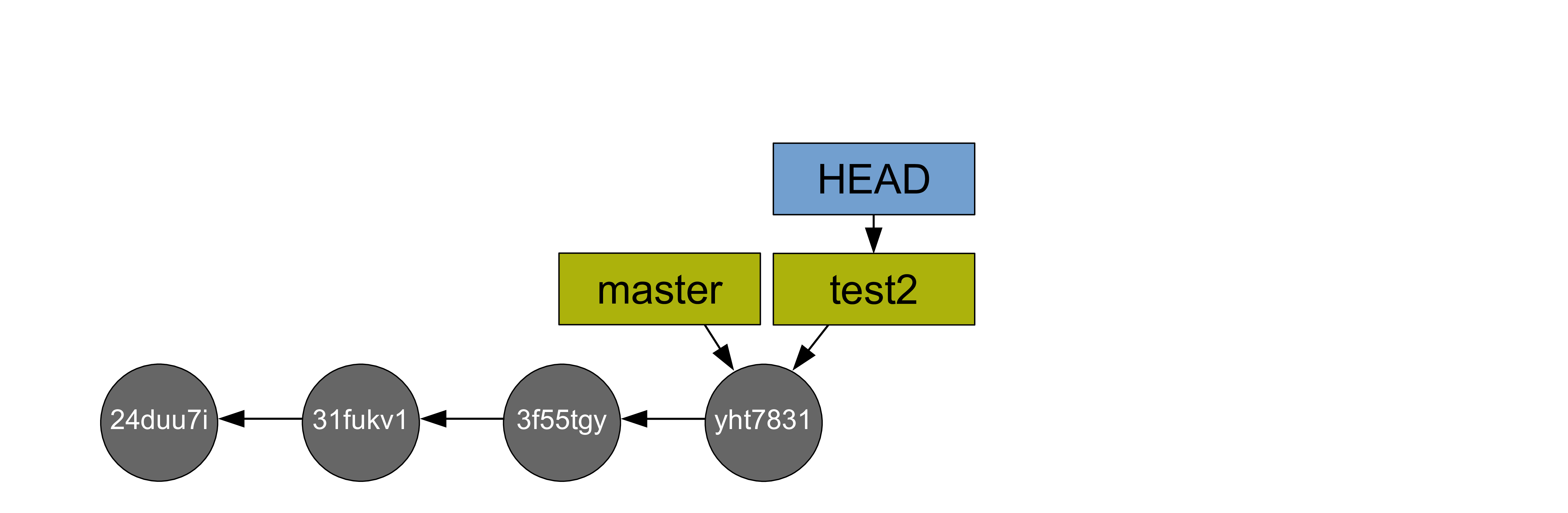

git checkout test

git status

git branch

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

Working with branches

Creating a branch & switching to it immediately

When you create a branch, most of the time you want to switch to it. So there is a command which allows to create a branch and switch to it immediately without having to do this in two steps: git checkout -b <branch-name>.

This command is convenient: when you create a branch with git branch <branch-name>, it is very easy to forget to switch to the new branch before making commits!

git checkout -b dev

git status

git branch

Working with branches

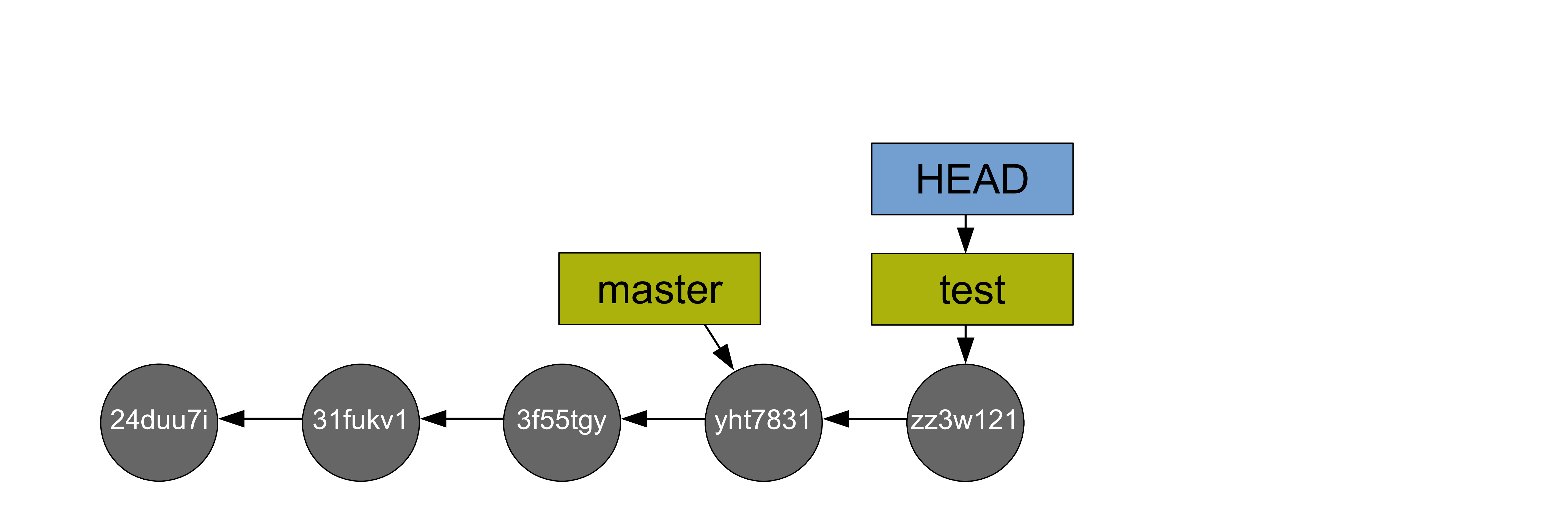

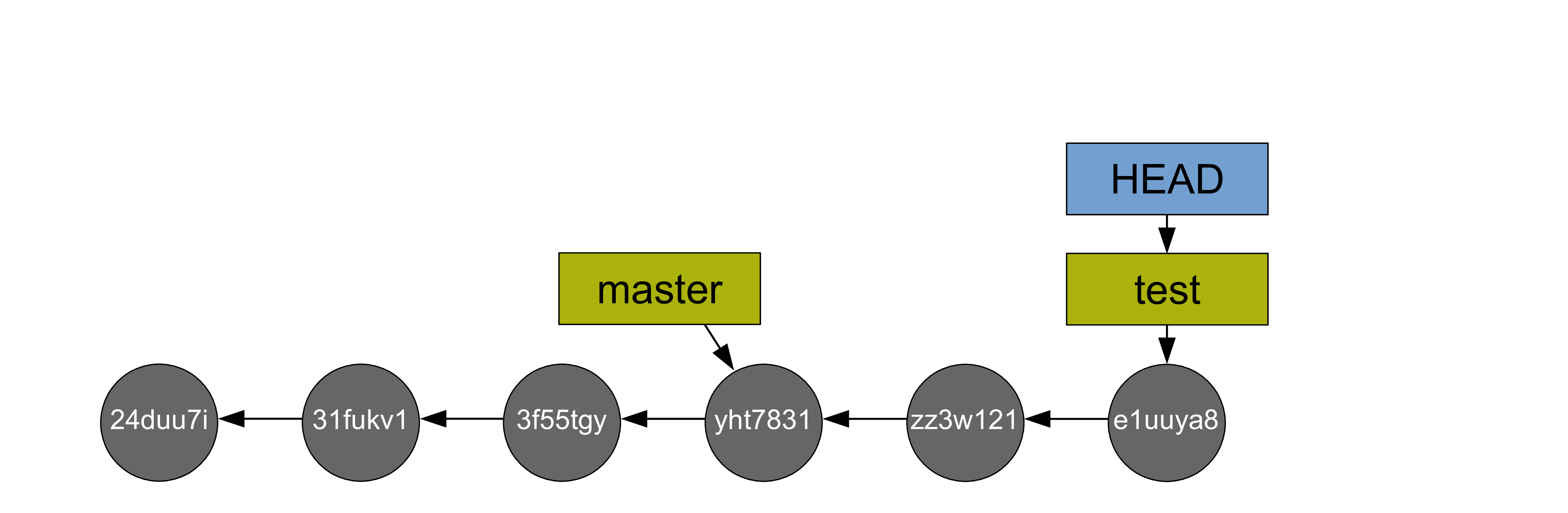

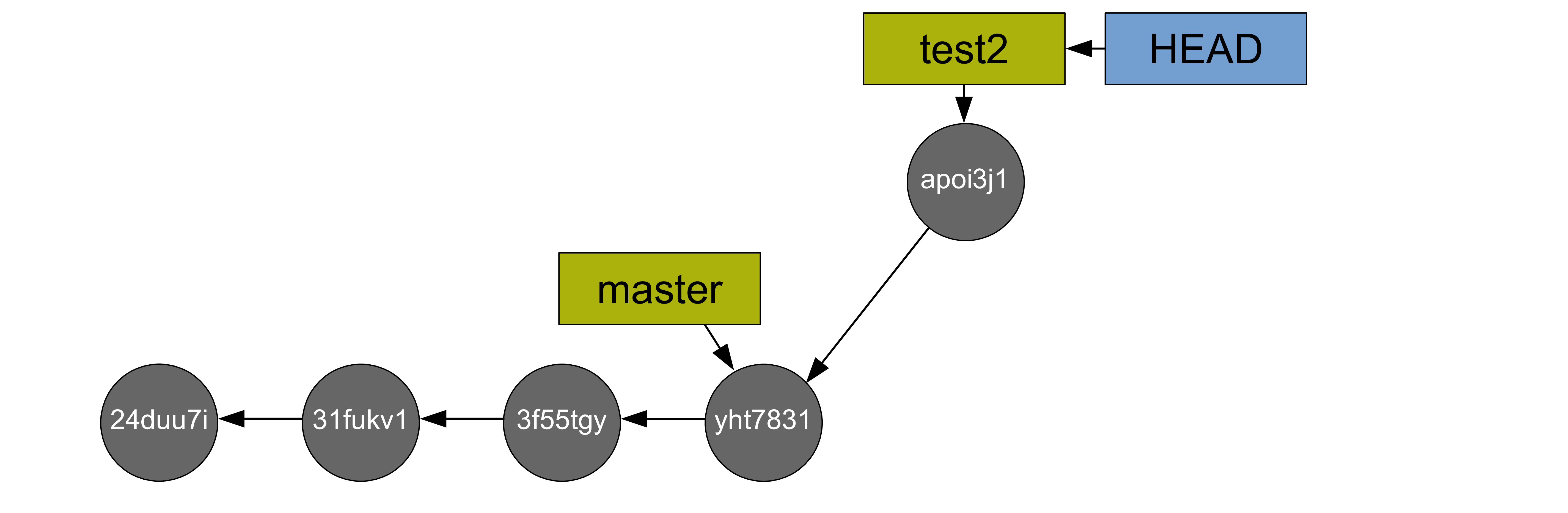

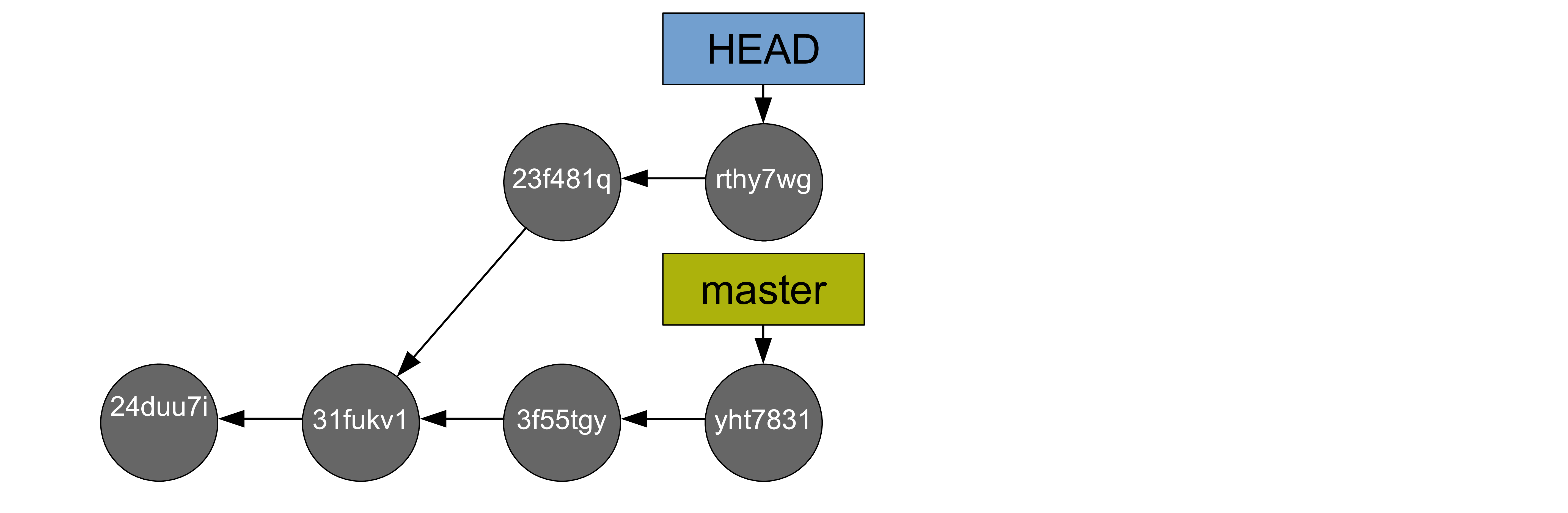

Creating commits on the new branch¶

git checkout test

touch src/acidity.py

git status

git add src/acidity.py

git status

git commit -m "Add new acidity script"

git status

echo "Some content" >> src/acidity.py

git status

git commit -a -m "Add some content to acidity script"

git status

ls src/

tree

git checkout master

git status

ls src/

tree

git checkout test

ls src/

tree

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

git diff test master

git diff master test

git diff dev master

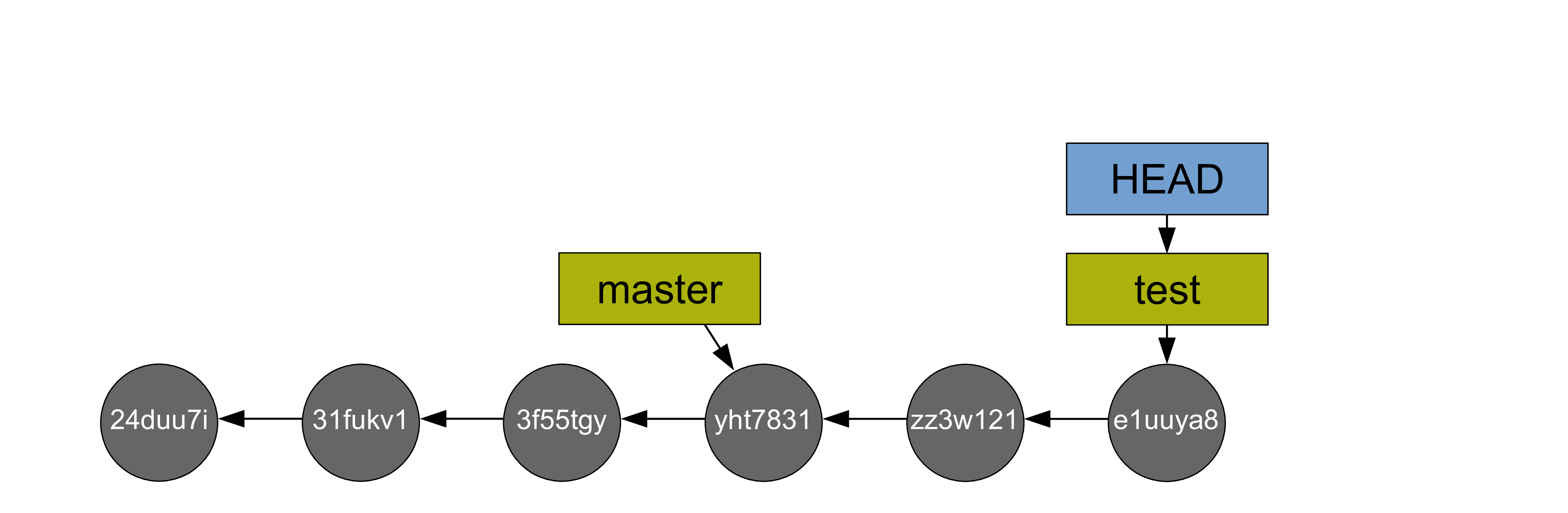

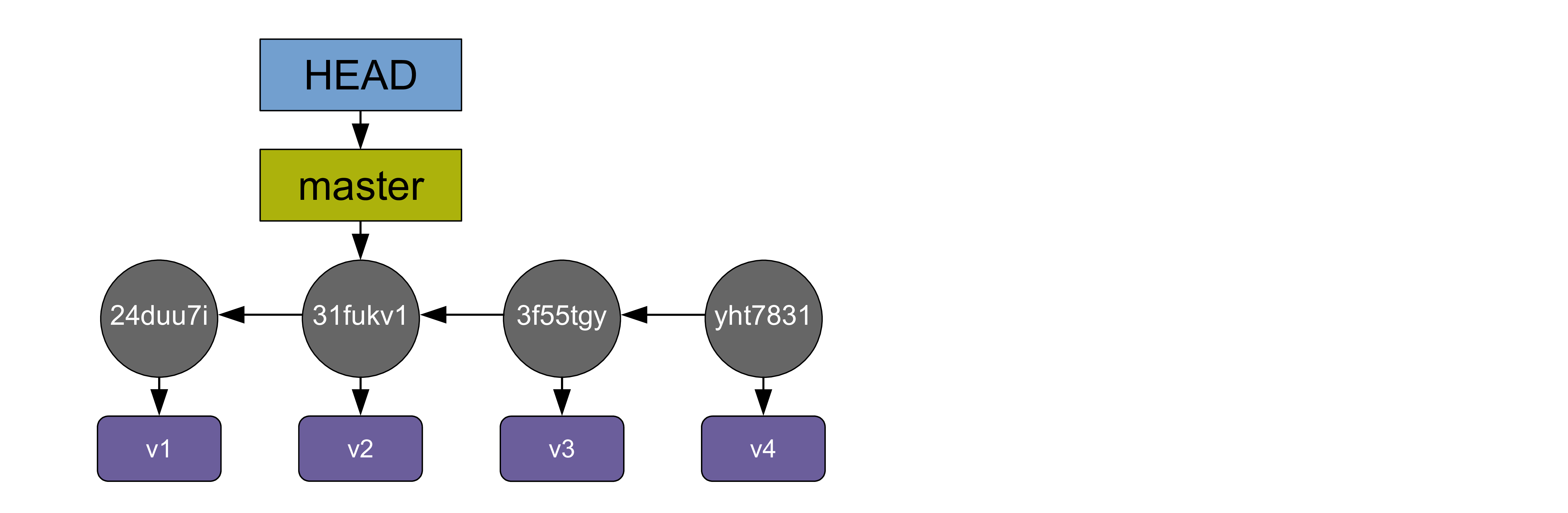

Working with branches

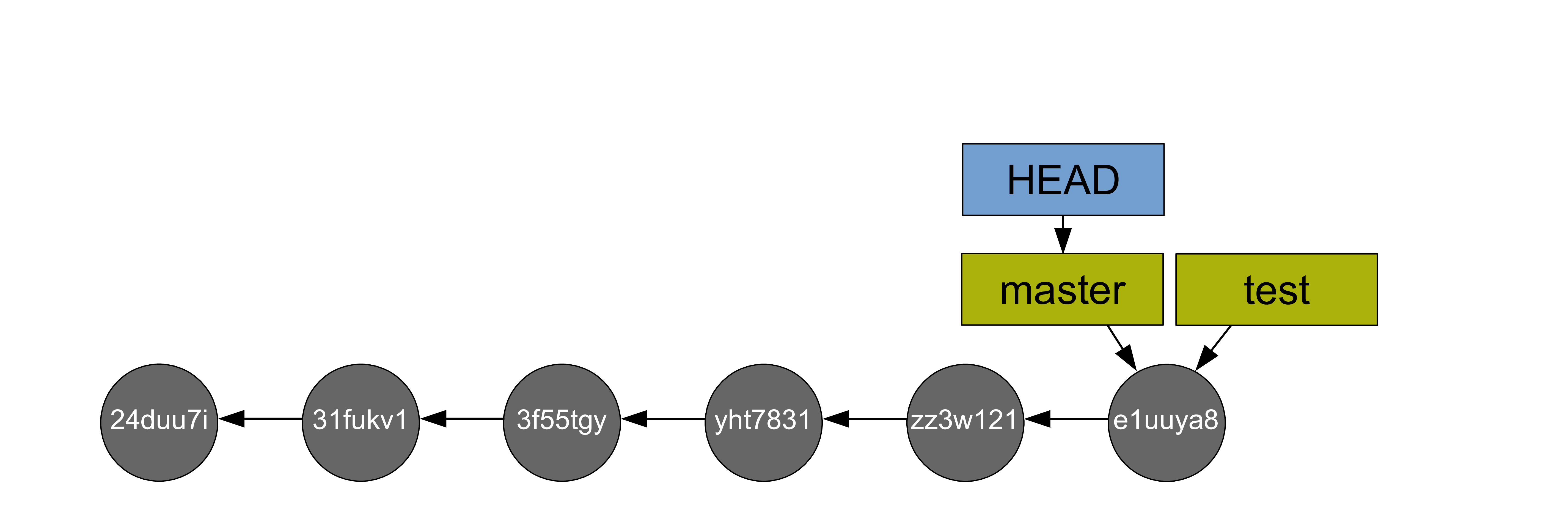

Merging branches¶

One thing that makes Git branches powerful is—as we just saw—how easy it is to create new branches and to switch from one branch to another. Another thing is how easy it is to merge branches together.

If you created an experimental branch and are happy with the result, you'll want to merge it into your main branch.

First, switch to the main development branch, then merge your experimental branch into the main branch:

git merge <branch-to-merge-into-current-branch>

git branch

git checkout master

git status

git merge test

git status

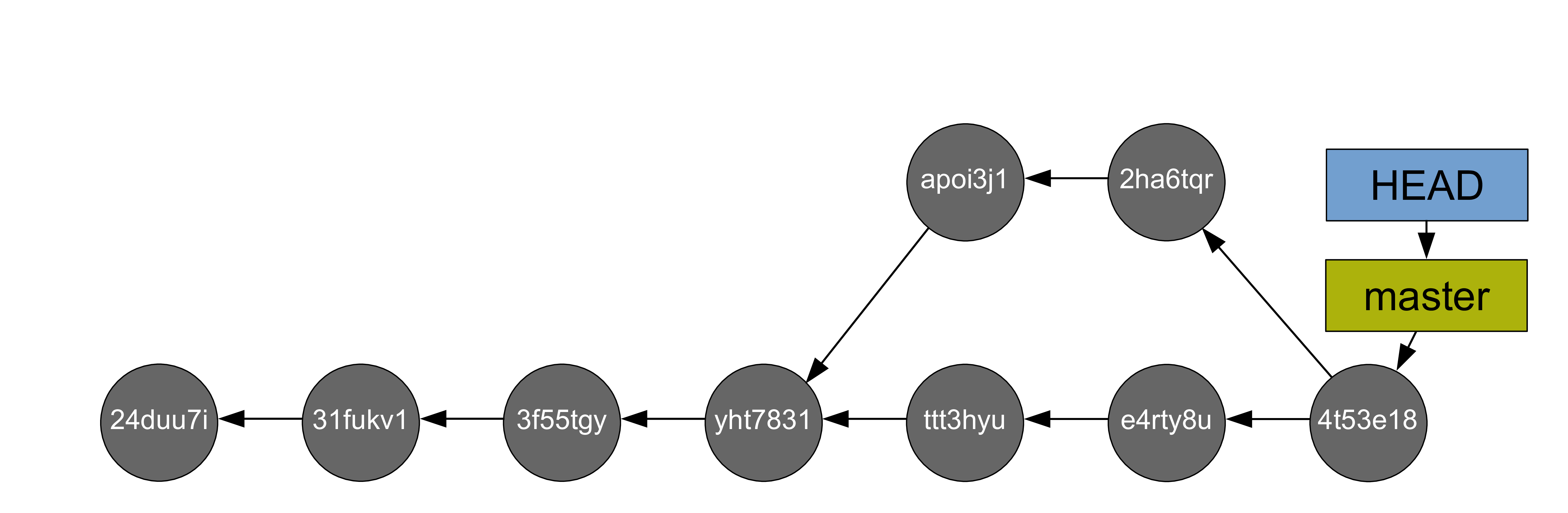

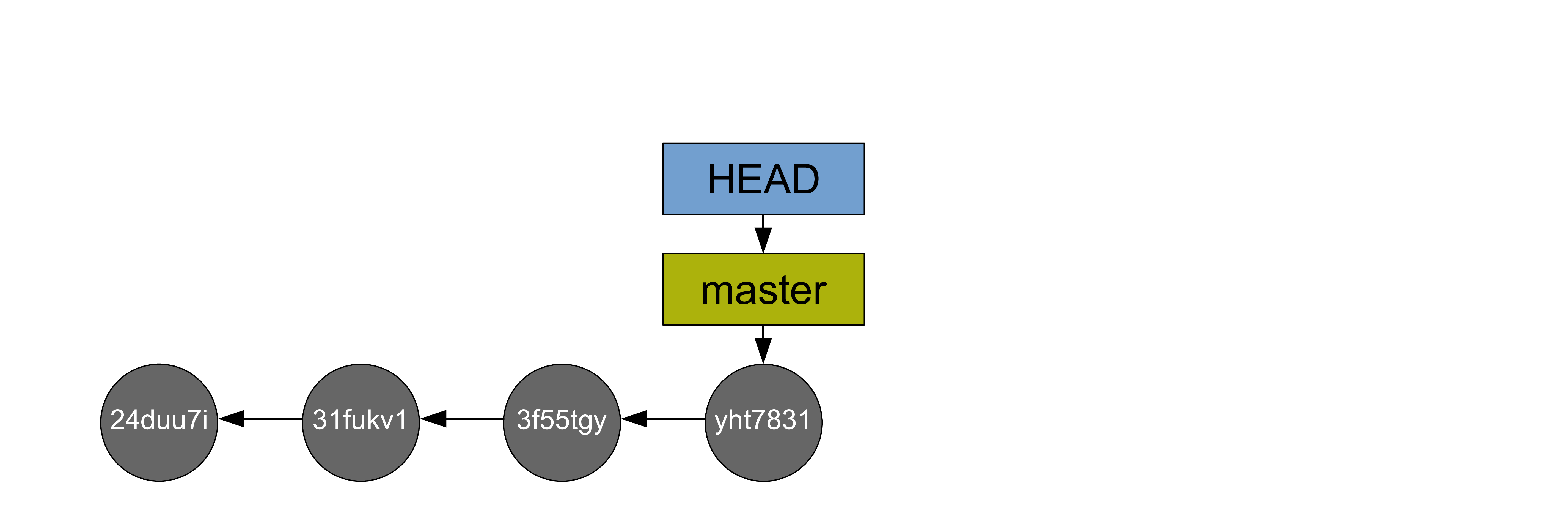

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

Working with branches

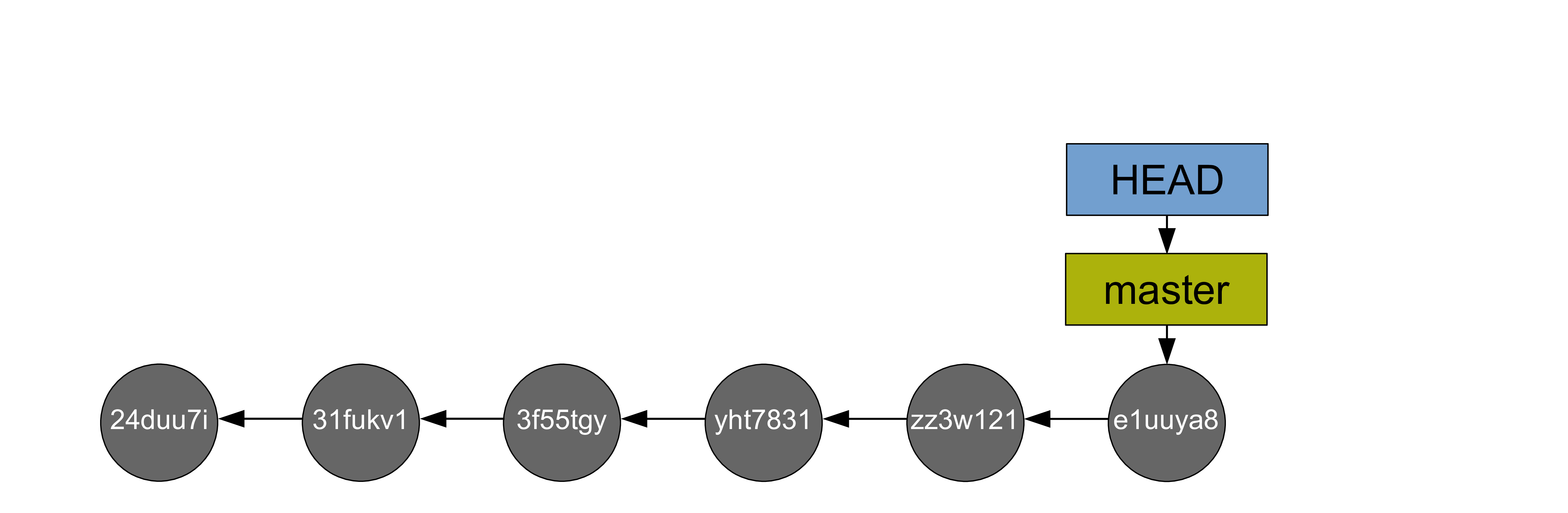

Deleting branches¶

Once you have merged a branch into another or if you decide that the experiments on a branch are not worth keeping, you can delete that branch.

To do so, we could run git branch -d test, but we will keep it for now as it will be useful later on.

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

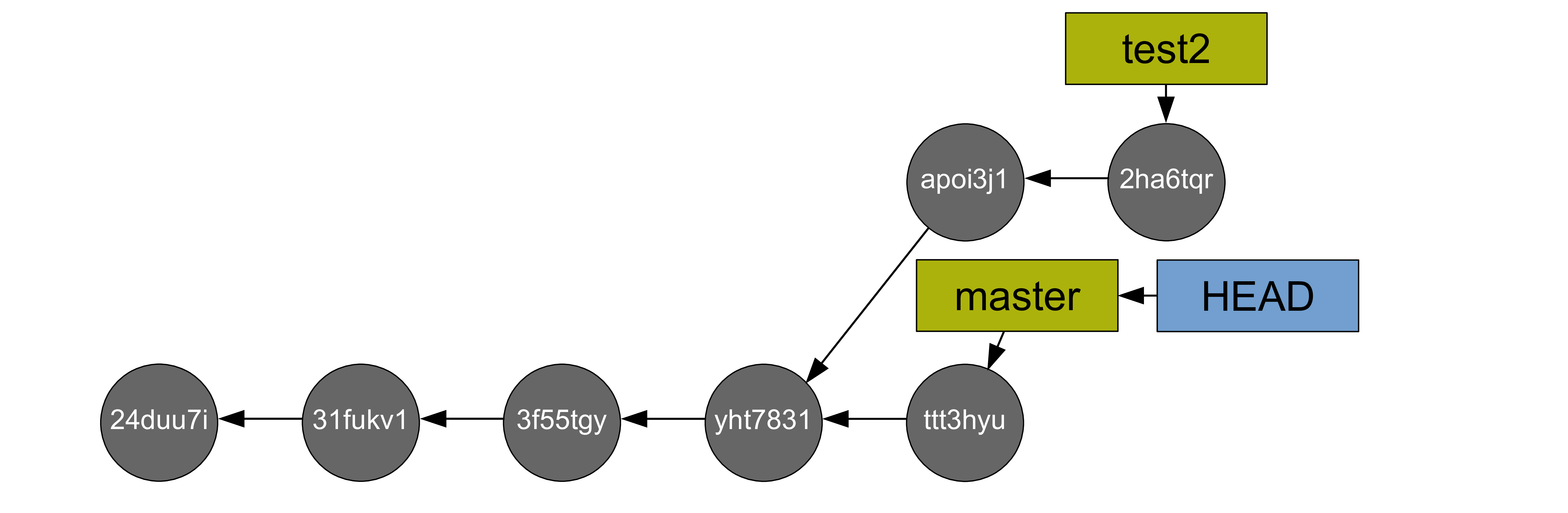

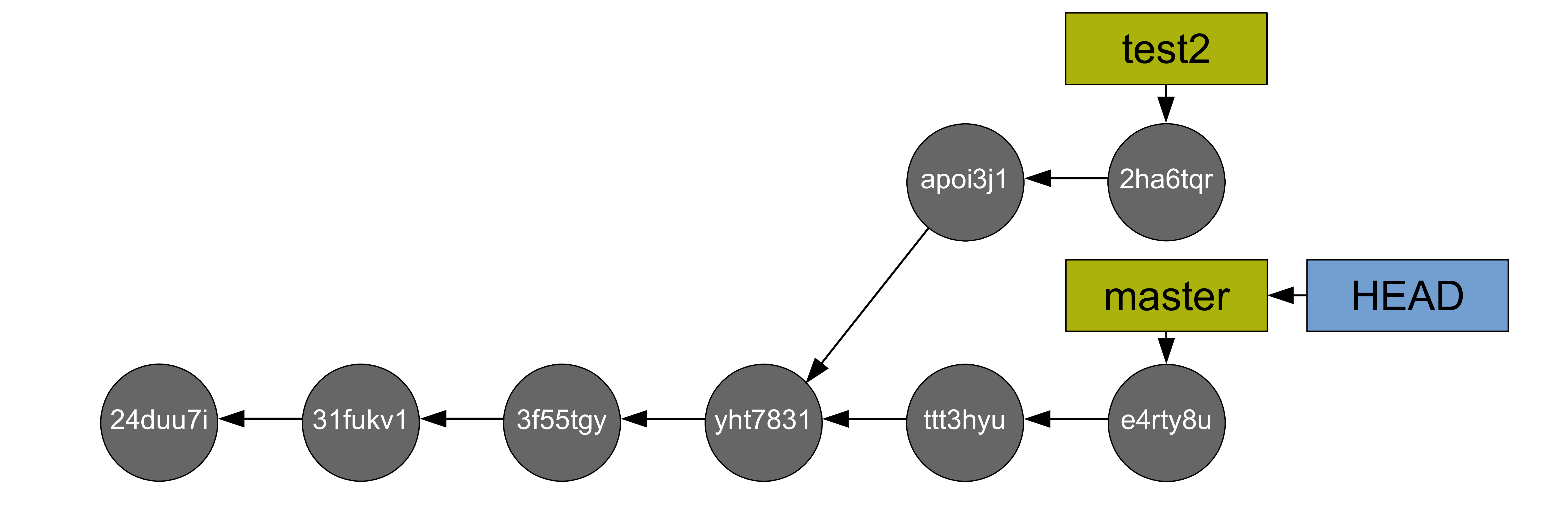

git branch test2

git checkout test2

echo "Some edits to the enso ms" >> ms/enso_effect.md

git commit -a -m "Edit enso ms"

git checkout master

echo "Add some code to the script" >> src/enso_model.py

git commit -a -m "Add code enso script"

git merge test2

# git branch -d test2 (not run because I will use it later)

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

Working with branches

Merge conflicts¶

As you were developing your experimental branch, maybe you were also developing your main branch. As long as the differences between the branches do not overlap (you have been working on different parts of the project in each branch, which can include different parts of the same file), there is no problem.

If the two branches contain different versions of the same part of a file however, Git cannot know which of the versions you want to keep. The merge will then be interrupted and Git will ask you to resolve the conflict(s) before the merge can be completed.

Conflicts will look like this:

<<<<<<< HEAD

Version of this section of the file on your checkedout branch

=======

Alternative version of the same section of the file

>>>>>>> alternative version

Working with branches

Merge conflicts¶

git checkout -b test3

emacsclient -c ms/enso_effect.md

git status

git add ms/enso_effect.md

git commit -m "Make some edits enso ms"

git status

git checkout master

emacsclient -c ms/enso_effect.md

git status

git add ms/enso_effect.md

git commit -m "Make conflicting edits enso ms"

git status

git checkout master

git merge test3

git status

Working with branches

Resolving conflicts¶

Merge tools allow you to jump from conflict to conflict within a file and ask you to decide which version you want to choose for each of them (you can also write a combination of the two).

git mergetool

git mergetool --tool-help

Working with branches

Resolving conflicts¶

If you don't use any merge tool, you can edit those sections manually in any text editor.

You can also in one swoop keep our version (i.e. the version of the branch you are currently on or HEAD ) or all of their version (the alternative version of the file you are merging into your branch) for all of the sections.

git checkout --ours <file>

git checkout --theirs <file>

emacsclient -c ms/enso_effect.md

git status

git add ms/enso_effect.md

git commit

git status

Exploring the past¶

In its simplest form, it gives a list of past commits in a pager.

git log

Exploring the past

Overview of commit history¶

This log can be customized greatly by playing with the various flags.

git log --oneline

man git-log

Exploring the past

Overview of commit history¶

You can make it really clean and fancy:

git log \

--graph \

--date-order \

--date=short \

--pretty=format:'%C(cyan)%h %C(blue)%ar %C(auto)%d'`

`'%C(yellow)%s%+b %C(magenta)%ae'

git log \

--graph \

--date-order \

--date=short \

--pretty=format:'%C(cyan)%h %C(blue)%ar %C(auto)%d'`

`'%C(yellow)%s%+b %C(magenta)%ae'

git log --graph

git log --graph --all

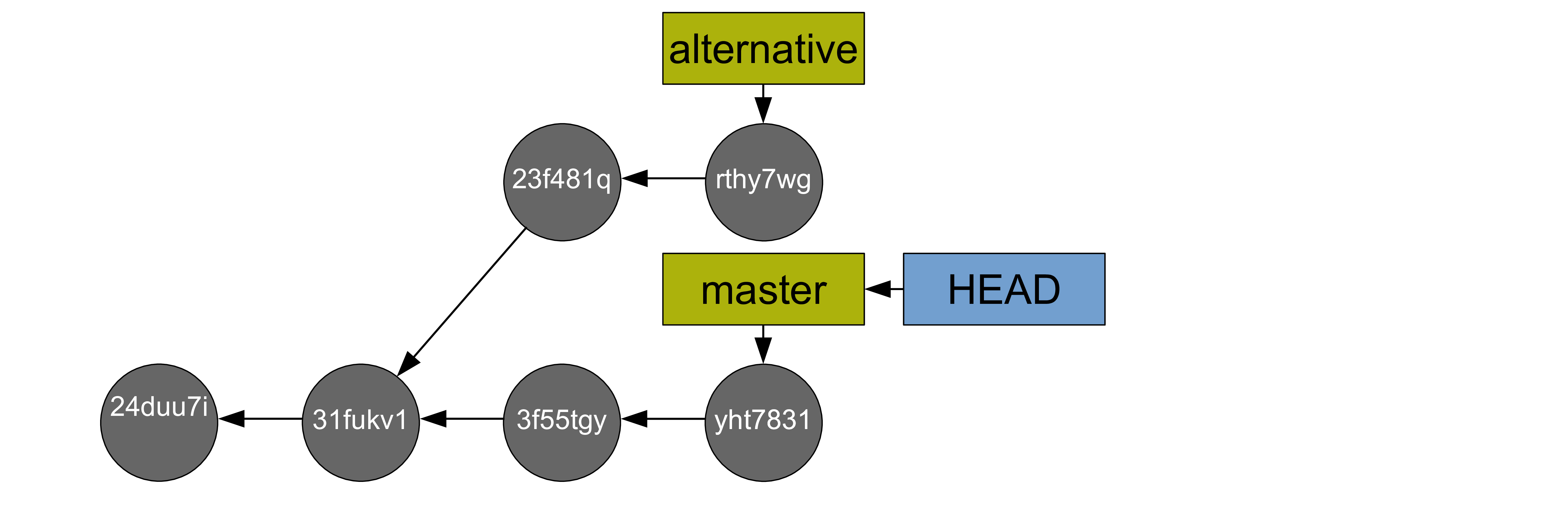

Exploring the past

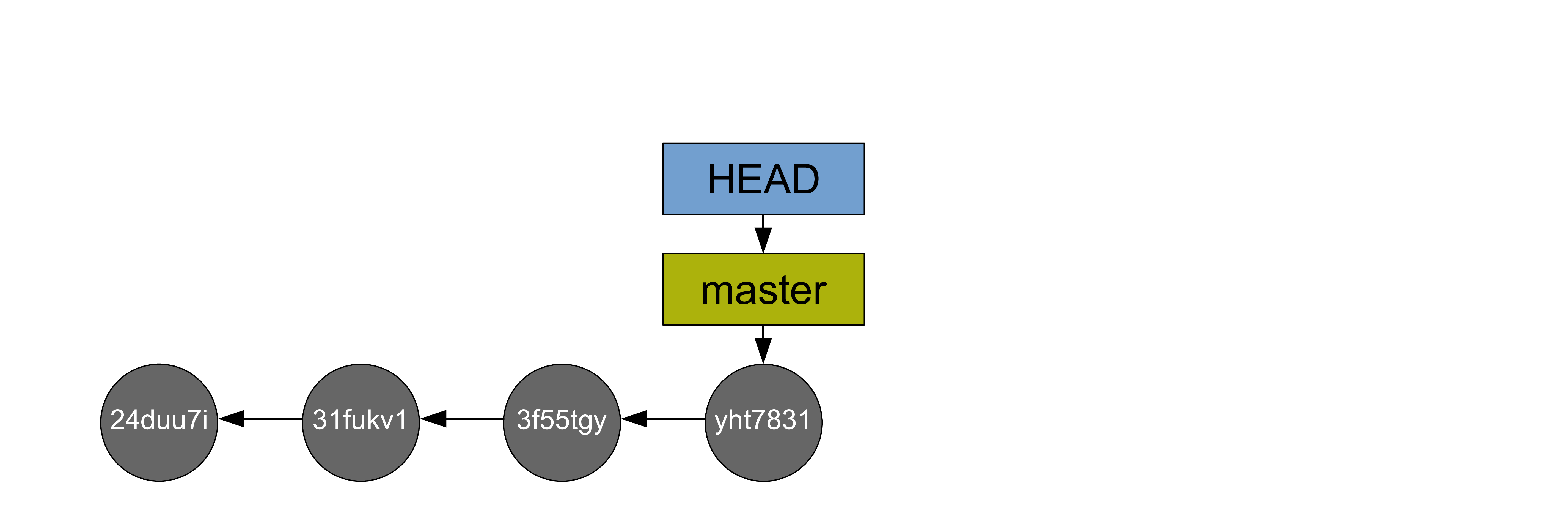

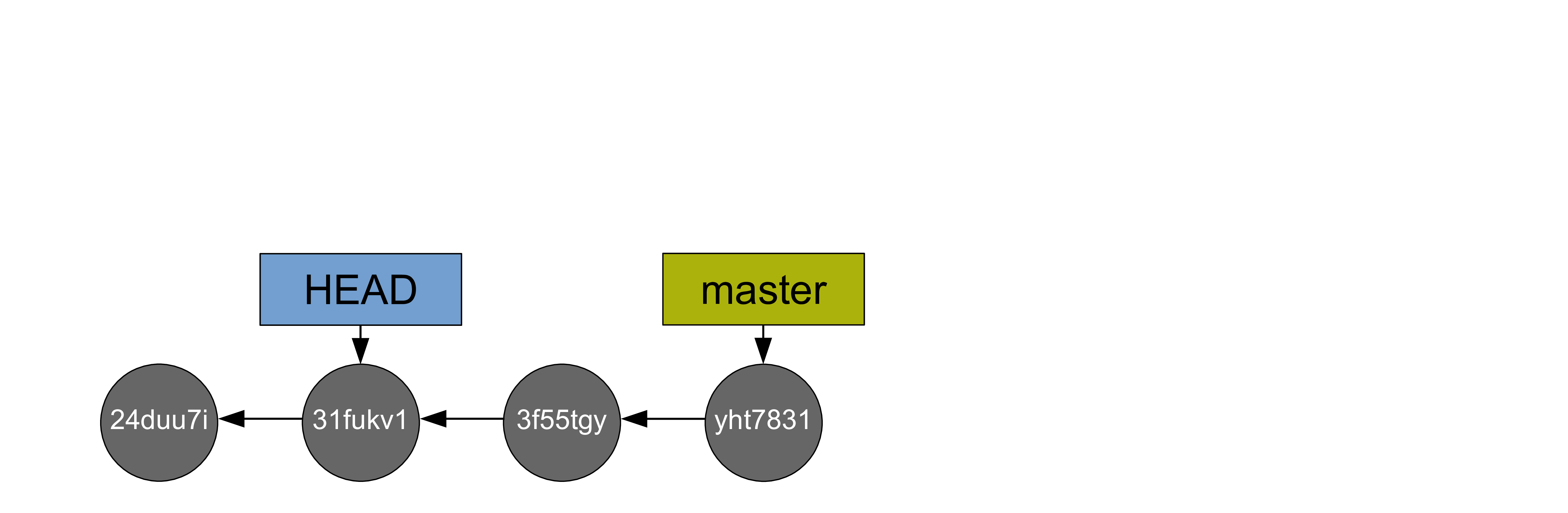

Revisiting old commits¶

git checkout <commit-hash>

You can also use tags:

git checkout <tag-name>

git checkout xxxx

git checkout master

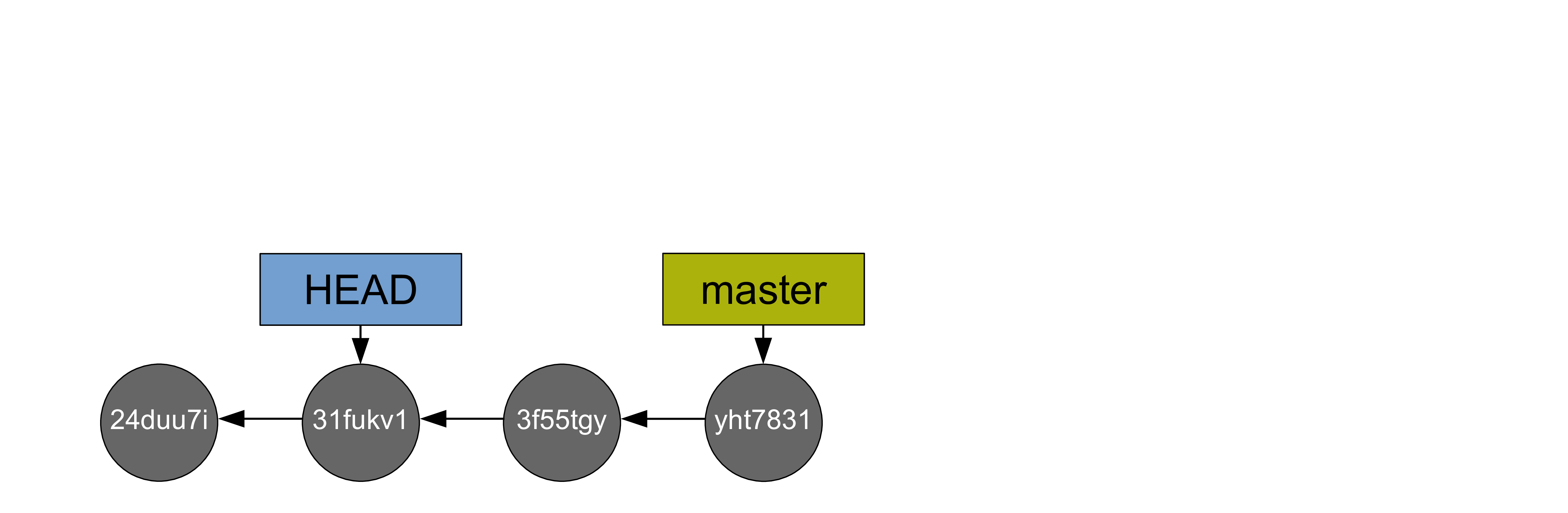

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

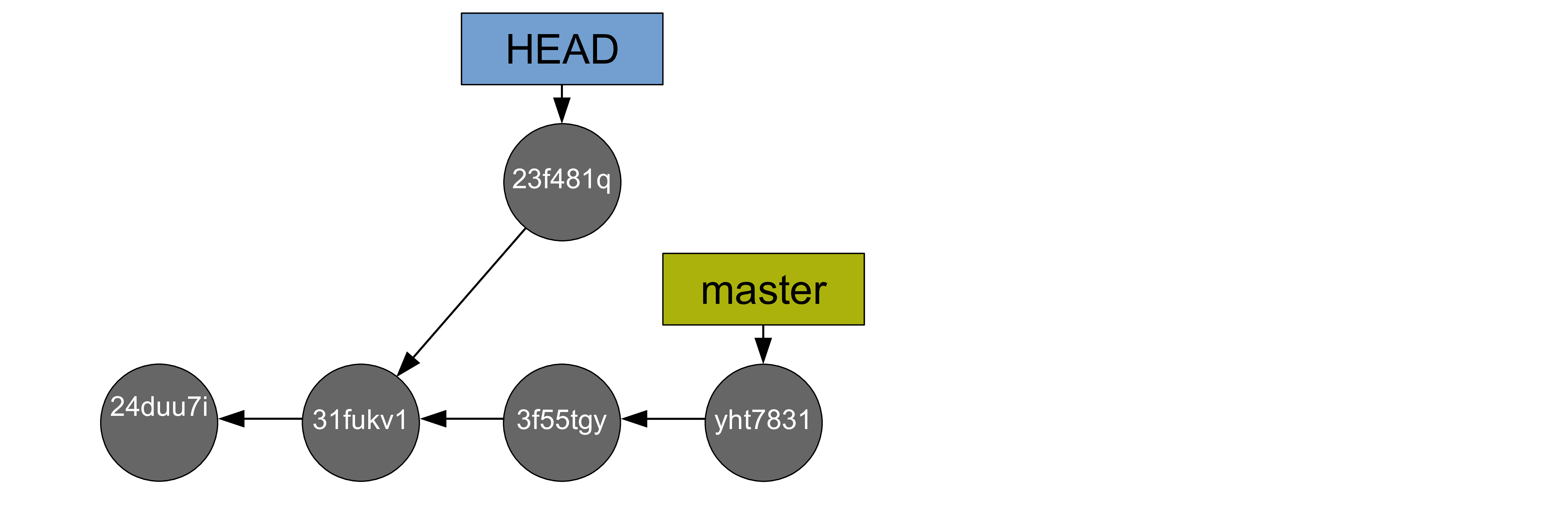

git checkout xxxx

echo "lala" >> ms/enso_effect.md

git status

git commit -a -m "Exploration from commit xxx"

git status

echo "tutut" >> ms/enso_effect.md

git commit -a -m "Another commit on that branch"

git status

git checkout master

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

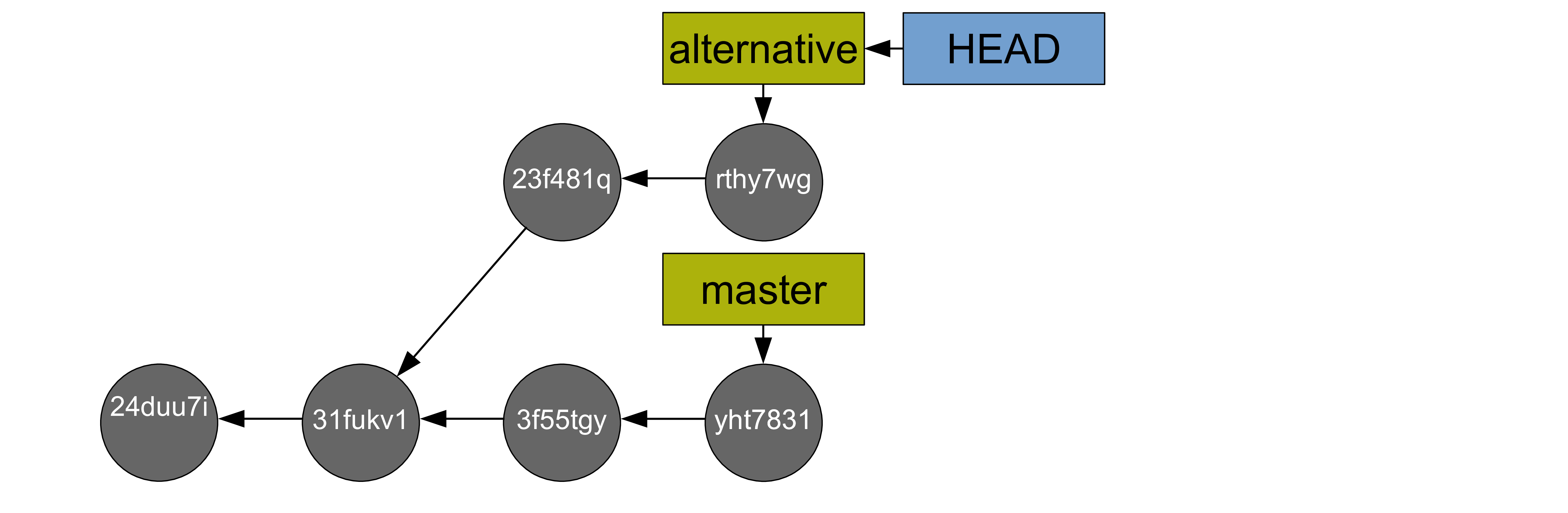

git checkout xxxx

echo "lala" >> ms/enso_effect.md

git status

git commit -a -m "Exploration from commit xxx"

echo "tutut" >> ms/enso_effect.md

git commit -a -m "Another commit on that branch"

git status

git checkout -b alternative

git status

git checkout master

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

git reflog

git checkout xxxx

git checkout -b new_branch

Undoing¶

Undoing

Codes¶

**Safe**

You can do this safely at any time as you can always go back to where you were before doing it.

**! Data loss**

Warning: this involves the loss of some information. Make sure that you do not want that information before doing this.

**! Collaboration**

Warning: this should not be done on something you already pushed to a remote when you are collaborating with others.

Undoing

Codes¶

**Safe**

Workflows with branches and git revert are safe. They can make for tortuous and messy histories however.

**! Data loss**

Information can be lost when you:

discard uncommitted work,

let the garbage collection eliminate commits that are not on a branch,

discard stashes that haven't been reapplied.

In any of these situations, make sure you really don't want to keep that data in your history.

**! Collaboration**

Whenever you touch at commits, there is a potential for messing up the workflow of collaborators.

Best to keep these for local work.

For local work (before pushing to a remote) however, they allow to fix horrible histories.

Undoing

Reverting **Safe**

The working directory must be clean.

Create a new commit which reverses the effect of past commit(s).

git log --graph --oneline

echo "Add line before reverting" >> ms/enso_effect.md

git commit -a -m "Add test line"

git log --graph --oneline

cat ms/enso_effect.md

git revert HEAD~

git log --graph --oneline

cat ms/enso_effect.md

git checkout HEAD~

git checkout -b new_start

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

Undoing

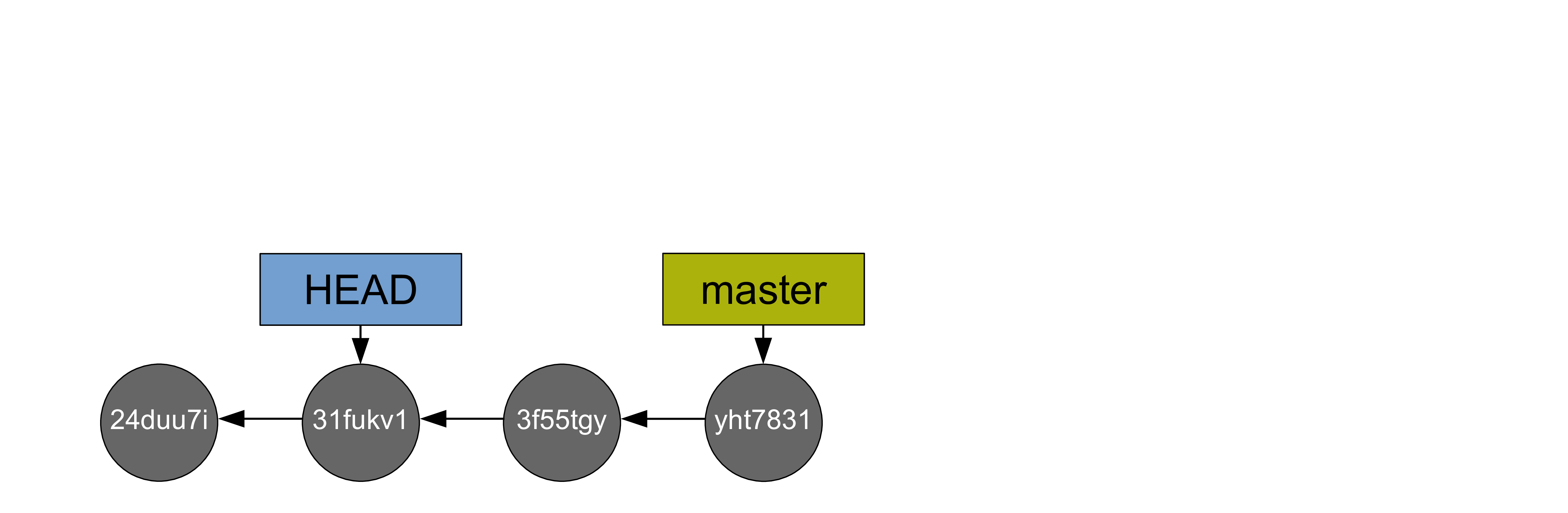

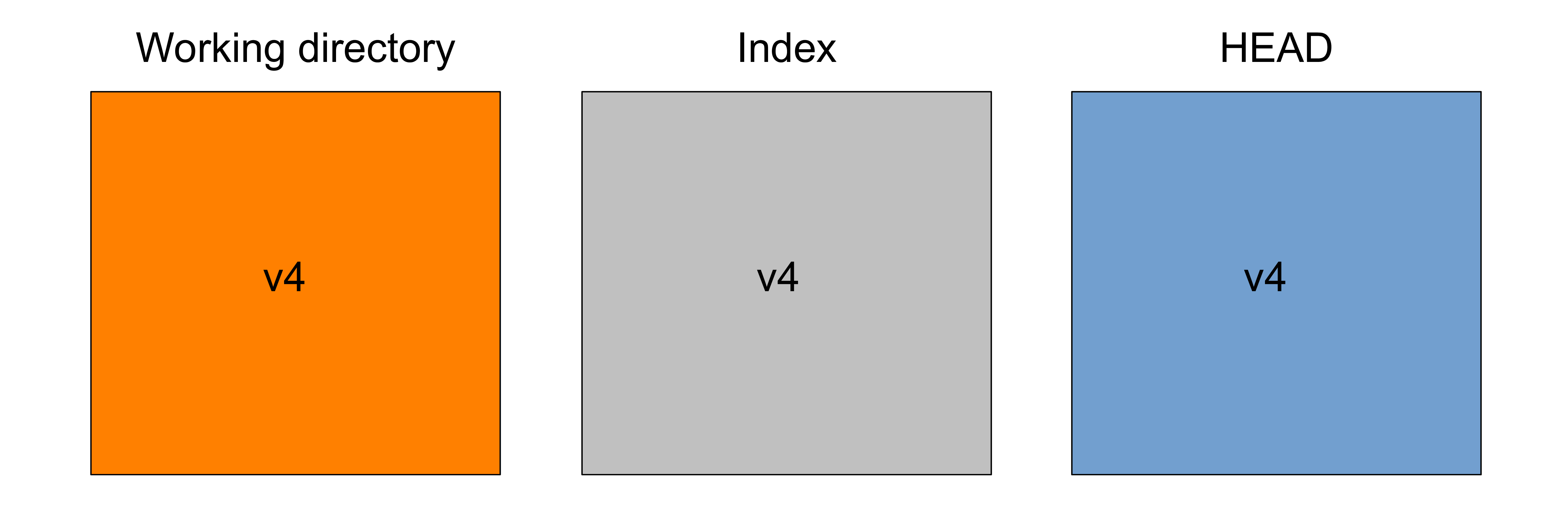

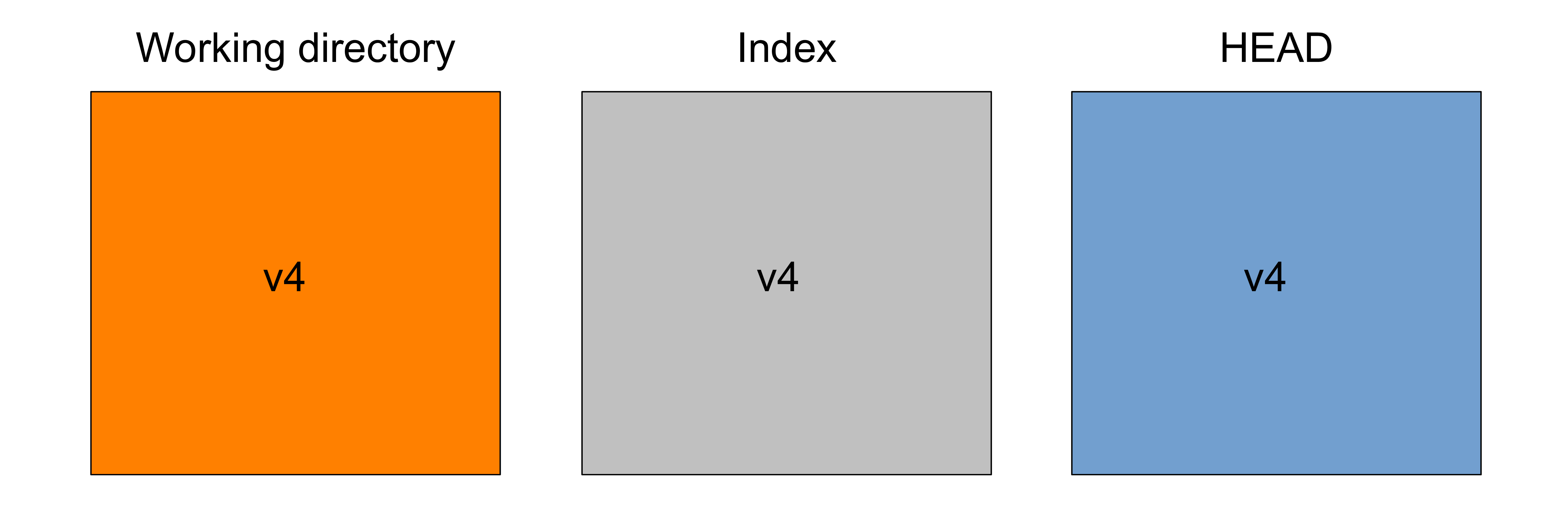

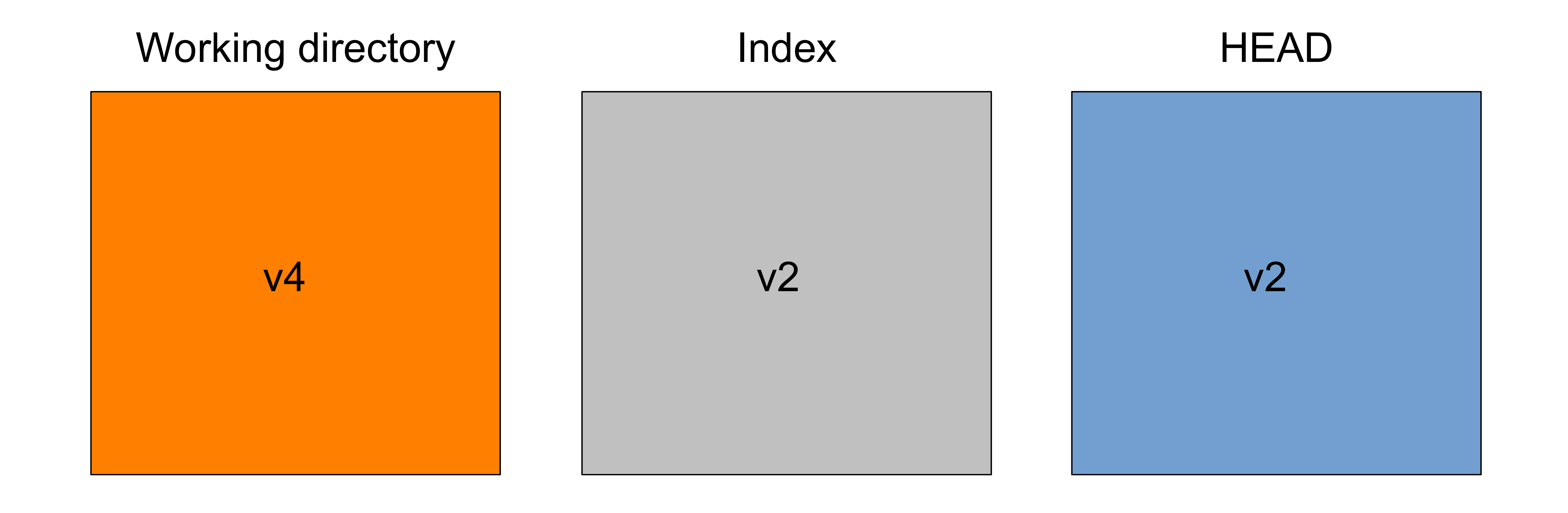

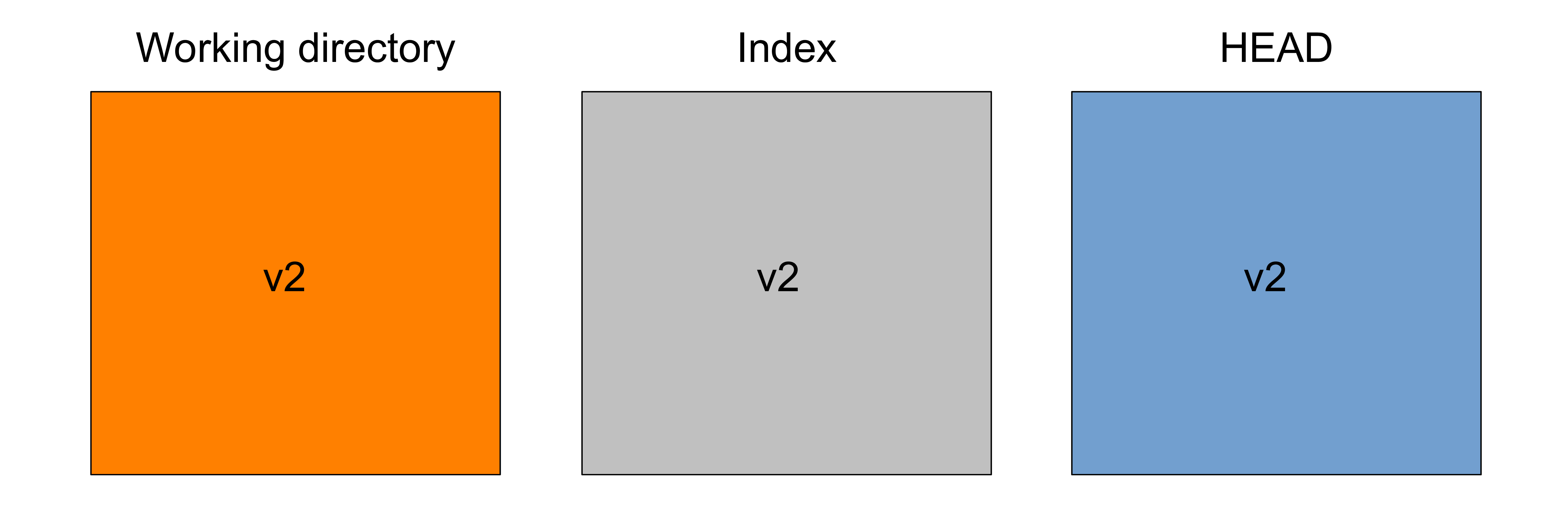

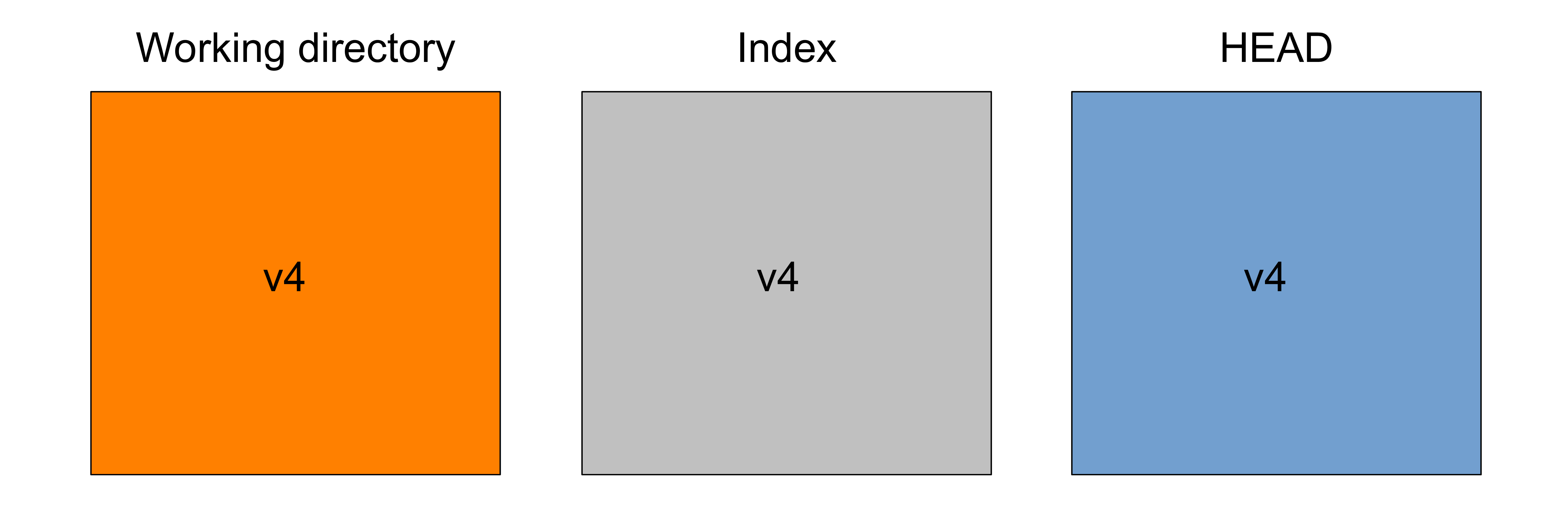

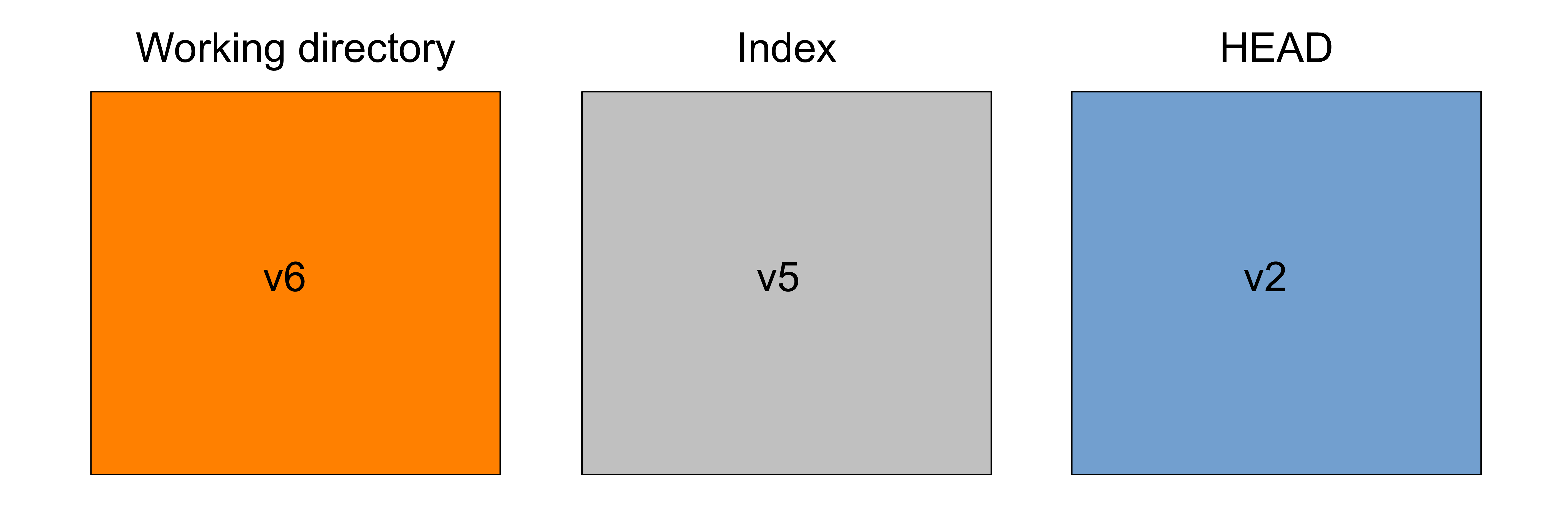

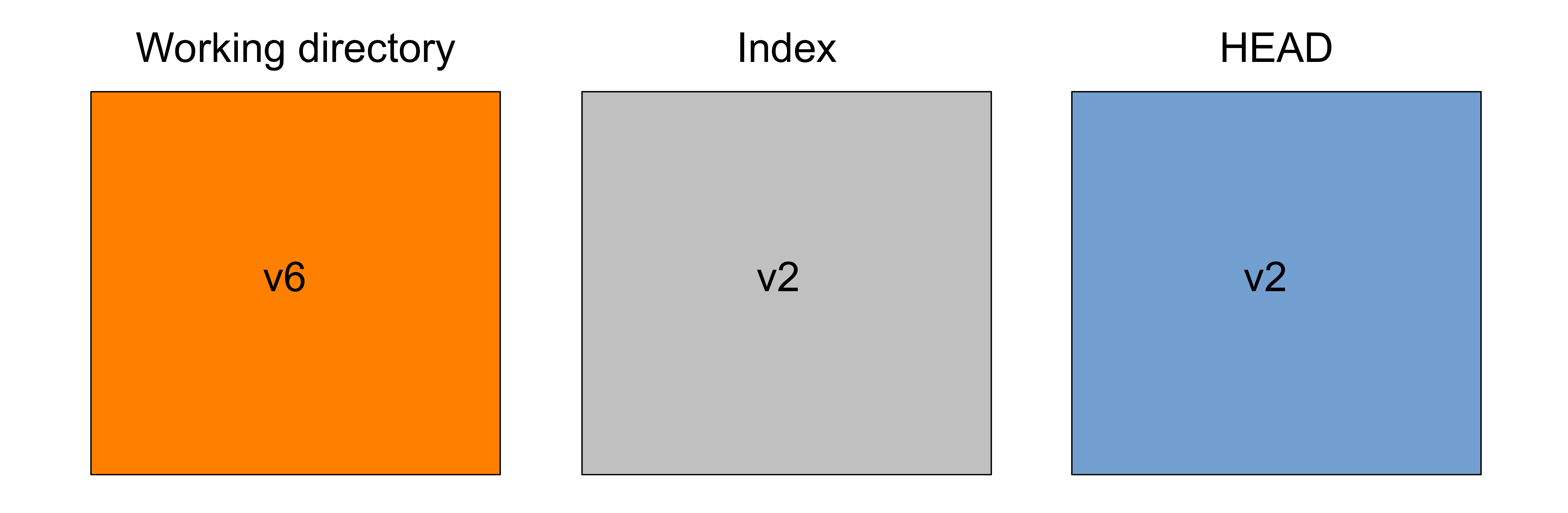

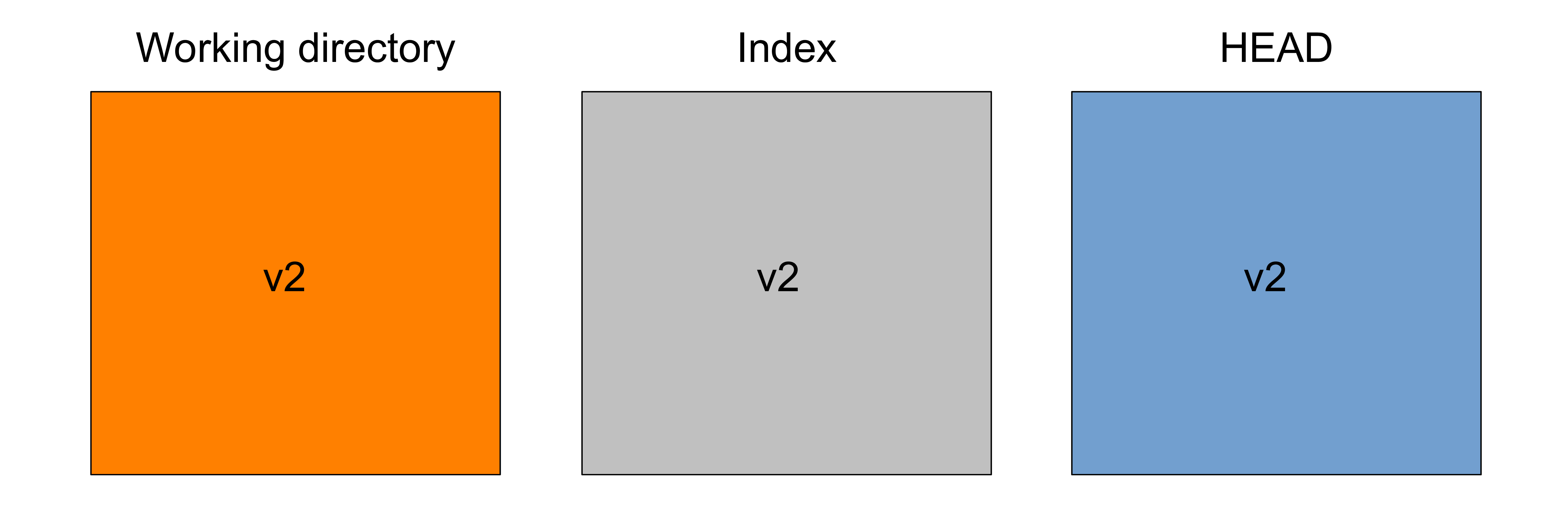

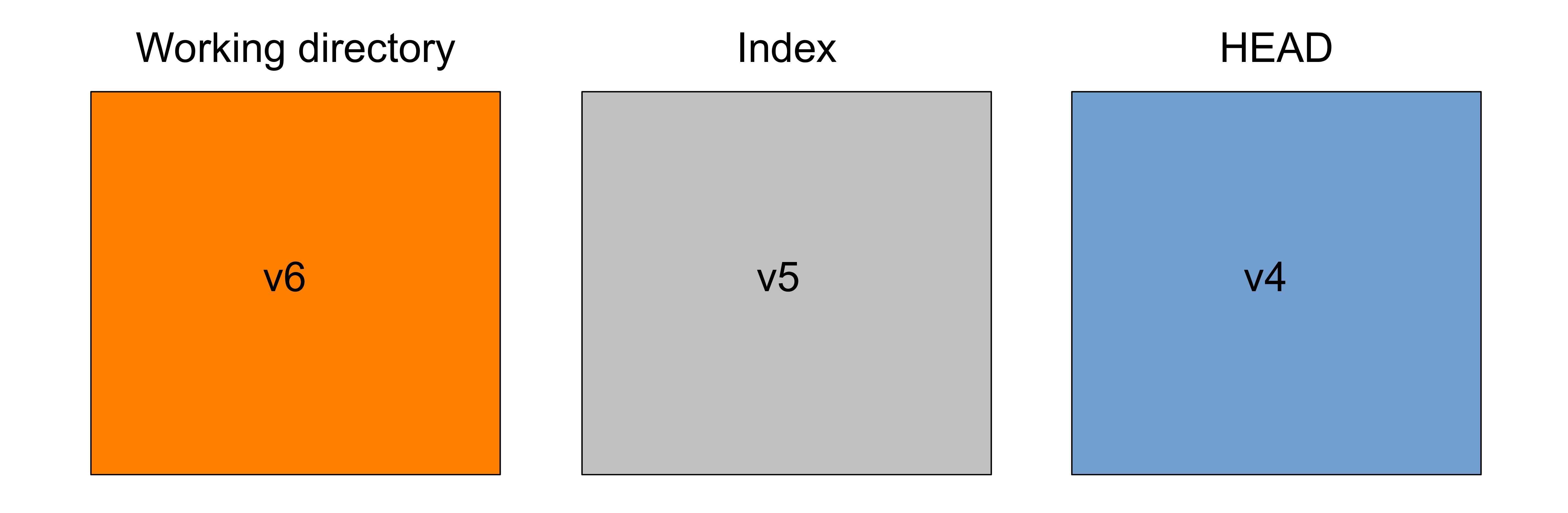

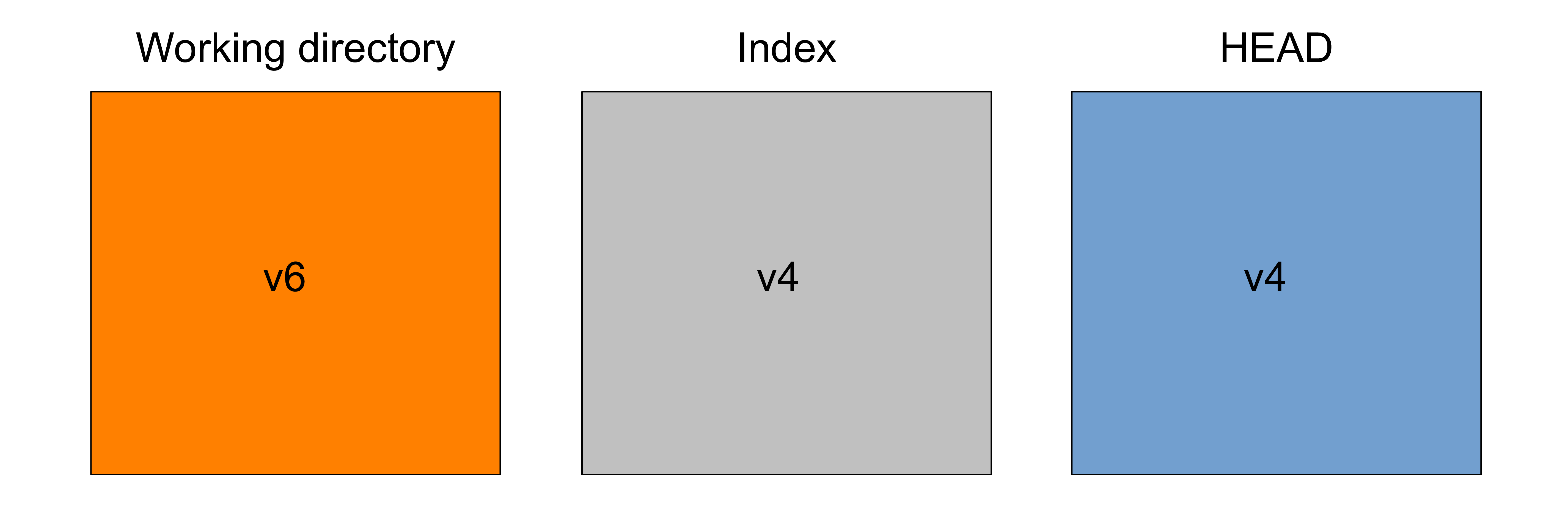

git reset --soft HEAD¶

**Under the hood**

**Under the hood**

Undoing

git reset HEAD¶

**Under the hood**

Undoing

git reset --hard HEAD¶

**Under the hood**

Undoing

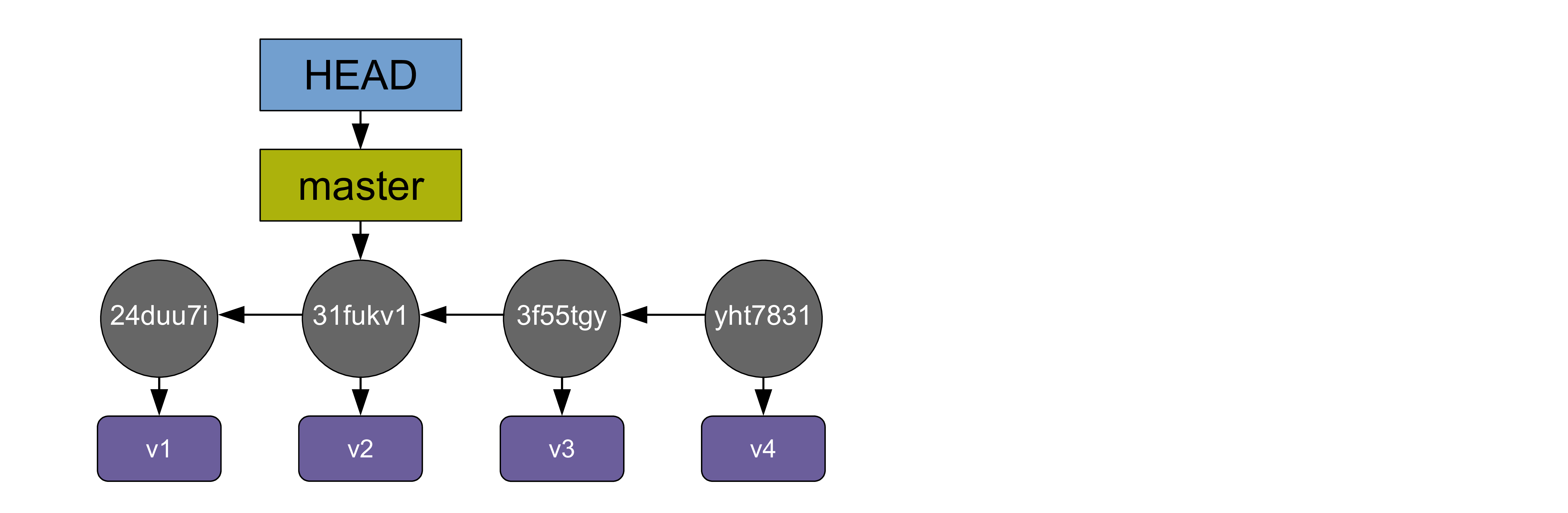

Undoing the last commit **! Collaboration**

git reset --soft HEAD~

Undoing

Undoing several commits

(while keeping the changes staged)

**! Collaboration**

git reset --soft HEAD~x

Undoing

Restoring the index (unstaging) **Safe**

Single file:

git reset HEAD <file>

All files:

git reset HEAD

Note: for versions newer than 2.23, Git suggests using a new command: git restore --staged <file>

See my answer on Stack Overflow for more details.

Undoing

Restoring the index (unstaging) **Safe**

Undoing

Undoing the last commit and unstaging

**! Collaboration**

git reset HEAD~

Undoing

Undoing several commits and unstaging

**! Collaboration**

git reset HEAD~x

Undoing

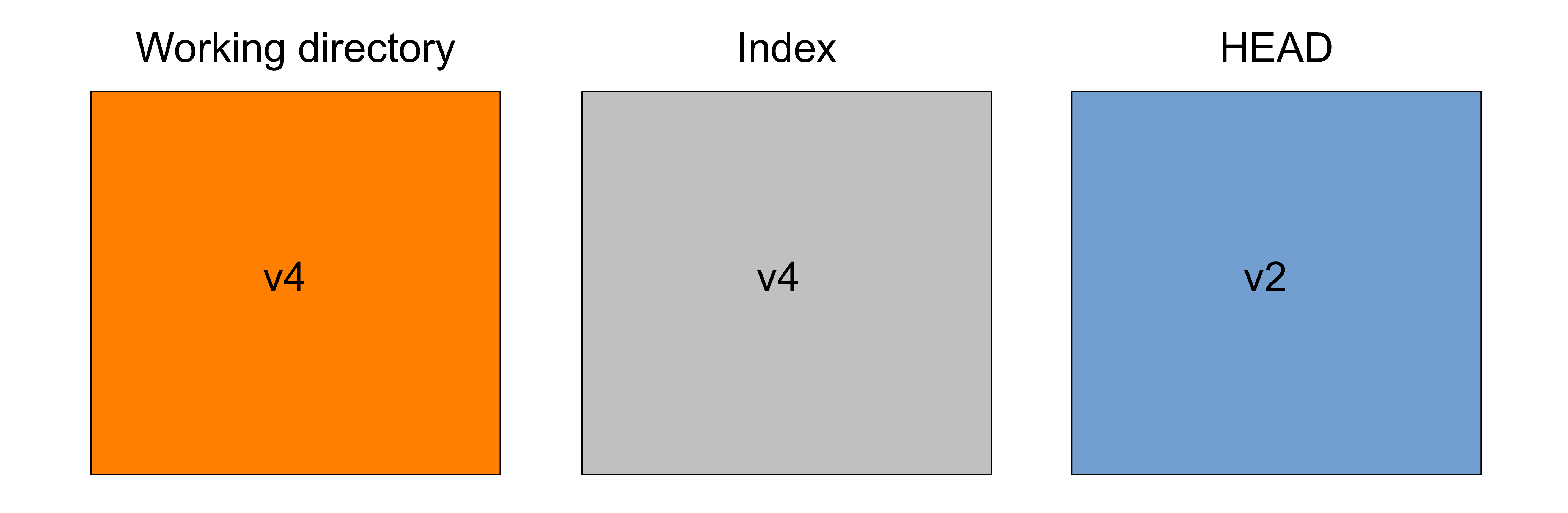

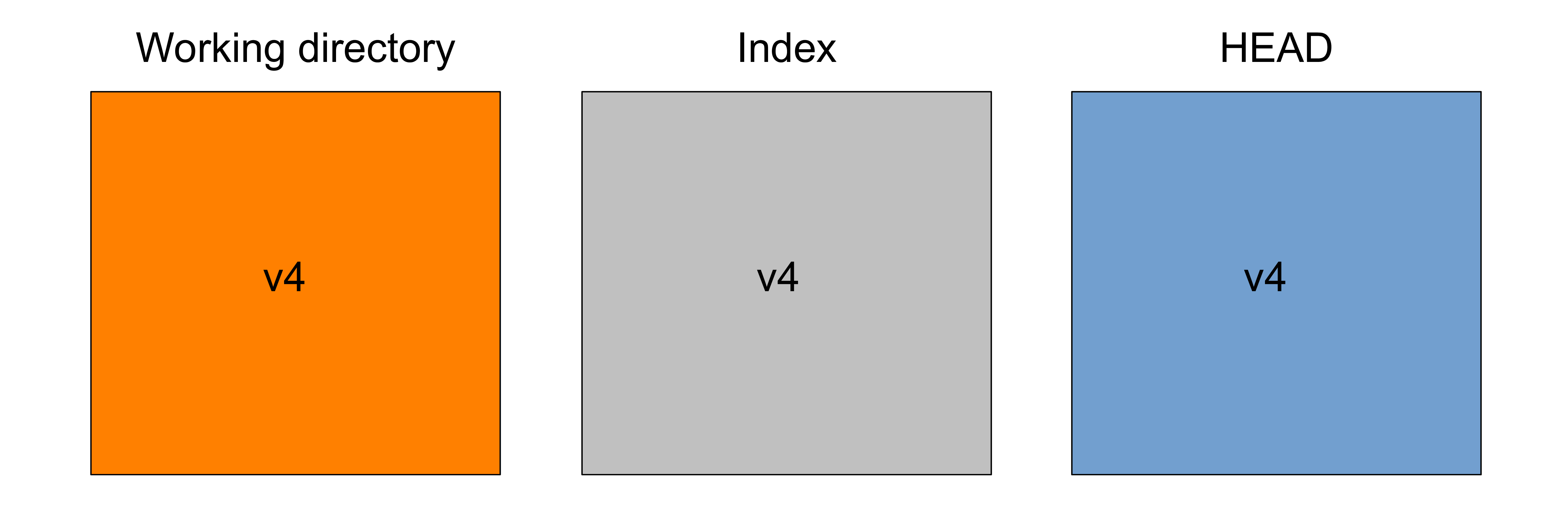

Throwing away changes since last commit

**! Data loss**

git reset --hard HEAD

Undoing

Undoing the last commit

& throwing away changes

**! Collaboration** **! Data loss**

git reset --hard HEAD~

Undoing

Undoing several commits

& throwing away changes

**! Collaboration** **! Data loss**

git reset --hard HEAD~x

Undoing

Throwing away unstaged changes (unmodifying) **! Data loss**

Single file:

git checkout -- <file>

All files:

git checkout -- .

Note: for versions newer than 2.23, Git suggests using a new command: git restore --staged <file>

See my answer on Stack Overflow for more details.

Undoing

Throwing away unstaged changes (unmodifying) **! Data loss**

Undoing

Modifying the last commit message

**! Collaboration**

git commit --amend -o

git commit --amend -o -m "Much better commit message"

Undoing

Modifying the last commit

**! Collaboration**

git commit --amend

git commit --amend --no-edit

git commit --amend -m "New commit message for the replacement commit"

Undoing

Modifying older commits

**! Collaboration**

git rebase -i HEAD~3

Remotes¶

Remotes

Adding remotes¶

Then, add it to your project¶

git remote add <remote-name> <remote-address>

The <remote-address> can be, amongst others, in the form of:

<user>@<server>:<project>.gitfor a server with SSH protocolgit@<hosting-site>:<user>/<project>.gitfor a web hosting service accessed with SSH addresshttps://<hosting-site>/<user>/<project>.gitfor a web hosting service accessed with HTTPS address

git remote add origin git@gitlab.com:prosoitos/ocean_temp.git

git remote add origin https://gitlab.com/prosoitos/ocean_temp.git

git remote

git remote -v

Remotes

Pushing¶

git push <remote-name> <branch-name>

To associate a branch with a remote, you can run:

git push -u <remote-name> <branch-name>

After which, you will only have to run:

git push

(Unless you want to push a new branch. Then you have to associate that new branch to the remote with -u as well).

git push origin master

git push

git push -u origin master

git push

git push origin --tags

git push origin --delete <tagname>

Collaborating¶

Collaborating

Cloning a repo¶

git clone git@<hosting-site>:<user>/<project>.git

git clone https://<hosting-site>/<user>/<project>.git

When cloning, the remote is automatically named origin and the main branch is automatically associated with the remote.

Let's practice with this project.

git clone git@gitlab.com:prosoitos/collab.git